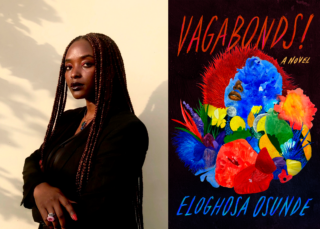

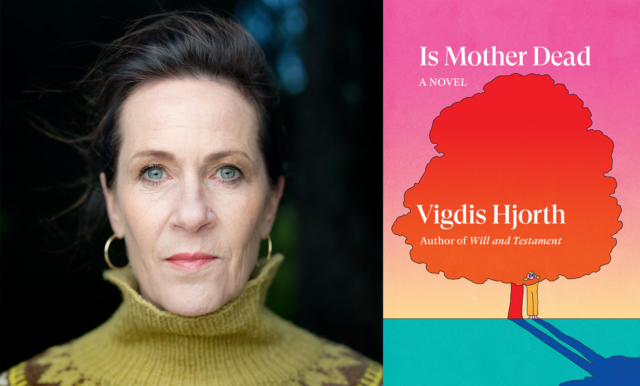

The author of over twenty books, Vigdis Hjorth is an eminent literary figure in Norway — if a Norwegian hasn’t read Hjorth, they know who she is. Only four have been translated into English, all by Charlotte Barslund, but they have likewise left a lasting impression on Anglophone readers. Her novel Will and Testament, for instance, explored the cover-up and denial of child abuse within a family that nearly matches Hjorth’s own. It was longlisted for the National Book Award for Translated Literature in 2019 and inspired debate, in both Norway and abroad, about the ethics of “reality literature.”

Is Mother Dead, Hjorth’s latest novel to be translated into English, tells the story of a painter named Johanna who is consumed by the desire to communicate with her aging mother, from whom she is estranged. Hjorth traverses Johanna’s emotional exile, the ruthless censorship within her family’s stories, and the language of art, in which the narrator takes solace. As with all of Hjorth’s work, there’s an undercurrent of existentialism. Midway through the novel, Johanna asks: “Do I confront my deepest self?” This question is a perfect description of the experience of reading any of Hjorth’s books: in witnessing a Hjorth narrator reckon with their innermost being, readers are enjoined to scrutinize their own hearts.

This is not to suggest Hjorth’s novels are exercises in mere navel-gazing. Quite the opposite — they reveal self-reflexivity as a political orientation. While conducting this interview, Hjorth was at the airport on tour for an even newer book just released in Norway about, in her words, “how all revolutions, personal as well as social, start long before the actual events.” With assistance from Barslund as translator, I asked Hjorth about Is Mother Dead, her prolific output, and the political project of her art. I started with Søren Kierkegaard.

You have cited Søren Kierkegaard, the father of existentialism, as a major inspiration for your work. I think your writing embodies Kierkegaard’s philosophy on a deeply energetic level — it forces us to reckon with ourselves, just as Kierkegaard has us reckon with the alienation of consciousness. Your rhythm, repetitions, and pacing demand we dwell with the thoughts that spiral in your narrators’ minds. Can you speak about your writing in the context of Kierkegaard’s philosophy?

At the age of nineteen, I began my studies at the University of Oslo and Kierkegaard’s Philosophical Fragments was on my required reading list. I read it without understanding a word, but I had a vague feeling that I was in the presence of something important, what Freud calls “the navel of the dream,” which opens a channel to the unknown and mysterious. What Freud, along with Kierkegaard, believed is that there are pathways to knowledge about life and the human condition to be found outside science, laboratories, and statistics. Some years later when I was going through a major crisis and was on my way to New York, I packed my Kierkegaard and read about different life stages. I understood, in the transatlantic twilight, that I was a middle-class, bourgeois woman, married to a middle-class, bourgeois man, that I had given birth to three middle-class, bourgeois children, and that I had to get a divorce. Something I set about on my return. So reading Kierkegaard really can change your life!

The most important thing for me is Kierkegaard’s insistence that being a totally ordinary human being is an enormous task and a declaration of faith from above, and that when you are lucky enough to be given this one life on earth as a human being, then you need to live it with complete sincerity and full responsibility. He writes somewhere that many people live in the basement even though there is plenty of room on the top floors where the view is broad and you can sense infinity.

I try — with Kierkegaard’s help — to climb from the basement to the top! As do many of my protagonists.

Your characters often grapple with the cruelty of neoliberal society. Alma, your narrator in A House in Norway, embodies the hypocrisies of “well-meaning” elites. Bergljot from Will and Testament reckons with secrets of abuse within her privileged family. Ellinor from Long Live the Post Horn!, a communications consultant, is tasked with storytelling as a device to save the local postal service — or, really, to pretend to save it, in the face of its inevitable demise. In a global context that is rife with xenophobic, classist anxiety, can you talk about the political project that fuels your work? Is your writing a response to the failures of civilization to exist justly?

To quote Berthold Brecht, who wrote this after the dropping of the nuclear bombs toward the end of World War II:

Will it be written on the last blackboard

the one that is broken and has no readers:

The planet is dying

killed by those it sustained.

We invented capitalism.

Then we became proficient at physics.

And invented mutual destruction.

The nuclear bomb has become a threat once more, but even if it isn’t dropped, then we appear to have invented another kind of mutual destruction — the climate crisis. And those of us who have the chance to do something about it, don’t, and those who already suffer the most in our unfair world, are the same people who will continue to suffer the most. We know this and yet we carry on. I know this, and yet I carry on. Right now I’m at the airport in Oslo about to fly to a literary festival in Røros. The problems of the international community are also my personal problems, but seeing as I’m unable to improve myself, I’m in no position to lecture the authorities. We/I get as angry with ourselves/myself as we/I do with the politicians. And so it is that otherwise well-informed, resourceful people end up suffering from profound self-loathing that stops them from taking action. But, to cite both Kierkegaard and Wittgenstein, you can — because the individual has agency — change your perspective. That is what great poetry does to us.

To quote the Chinese poet Du Fu:

The woman next door to you is a thief.

She still steals vegetables from your garden.

She is obviously still a widow — children grow slowly,

And, as you know, the war has made the poor poorer.

I don’t think she should be so scared of you when she steals.

I think your new fence is far too high.

I read it and I gain a fresh perspective and I’m inspired to act where I can: I’m working on tearing down my fence.

But — it is a challenge.

Of all of your books so far in English, Is Mother Dead explores nature most directly. There are so many stunning passages in which the narrator, Johanna, describes the woods around her cabin, the flowers that grow along the lanes, the ridges of hillside against the skyline, the way the light looks and feels, the mushrooms on the forest floor. I can’t help but think of “mother,” in some ways, as mother earth, and the question, “is mother dead” as directed toward our ongoing ecological crisis.

That thought hadn’t occurred to me, but you may well have a point. Johanna’s relationship to nature probably resembles mine. And Johanna’s relationship to her family does indeed resemble mine. However, I haven’t previously considered that Johanna, or indeed I, view nature as a substitute mother.

Most people have a complex and ambivalent relationship to their mother, including people who are close to their mothers. The point, however, is that Johanna’s relationship with nature isn’t ambivalent. It is essentially a calm and stable relationship. Which is why it is safe. I view nature as a place of peace and serenity precisely because it isn’t human. Because everything human is restless, unstable.

Can you speak about your process?

It is tricky to describe the writing process, because it is so complex — thoughts and reflections inextricably linked to a rhythm, a kind of linguistic music at sentence level and at paragraph and chapter level. The novel as a whole can be regarded as a piece of reflecting, linguistic music, and when I write there is often a strong connection between my head and my hands, and yes, sometimes the rest of my body, which — during certain passages — might sway with it. It is in other words, terribly complex — and wonderful for the most part.

But how do you begin?

I always start with an ethical or political dilemma that is personal to me. Then I explore it through writing a novel. I think of my novels as explorations. But I would never examine a personal dilemma if I thought it was unique to me. It is because I think I share this dilemma with many other people that I regard it as worthy of a novel. Then I look for a main character and her — and it usually is a her, but I have written about male protagonists — situation, and then it works itself out along the way, as the Danes say.

Who are your literary forebears and which contemporary writers excite you?

The Norwegian author Dag Solstad is a major inspiration, both in terms of themes, style and humor. As is Brecht, his poetry and plays are driven by ideas, his clever, thought-provoking conceits. And Thomas Bernhard’s manic, often furious yet tender prose. The Danish author Tove Ditlevsen’s frankness and fearlessness — nothing is too trivial to be examined. Among philosophers I’m fond of both Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, not because I necessarily agree with their theories, but because they write well, especially Freud. But my overarching inspiration is, as previously mentioned, Søren Kierkegaard. Precisely because he doesn’t devise ideologies but articulates his thoughts as he writes. His writing is incredibly stimulating.

When did you start writing, at what age?

I submitted my first poem to the Norwegian newspaper, Dagbladet, when I was ten years old. It went like this:

Who am I?

My eyes or my nose?

My mouth, perhaps all of my face.

Maybe it’s something I can’t change?

My legs or possibly my toes?

Or how about my brain?

After all, everything has a name, and all names have meaning

Except the word I which sits alone.

I wonder what that word means?

Many of your narrators share a similar status of scapegoat, or, psychoanalytically speaking, the “identified patient.” Can you speak about this idea of scapegoating? At times your work feels like a testimony — a way of making things right.

Unfortunately, writing can’t fix the past — but it is healing to articulate complex feelings and it can also be healing to read them, to see expressed something you sensed vaguely within yourself. That is the gift of literature. When it comes to the black sheep of the family, most families have a kind of official family narrative: in our family we celebrate Christmas like this, we celebrate Easter like this. If one family member doesn’t share this often very attractive family narrative, they will discover that there is an element of discomfort at their very presence. And so this person will often retreat. They don’t have to be frozen out; the rest of the family can in subtle ways induce shame in them, fear, force them to look downward, withdraw.

Your narrator in Is Mother Dead, Johanna, is an artist who has been exiled from her family for (supposedly) exposing family trauma in her work. At one point she reflects on a moment in her childhood, perhaps the most intimate experience with her now estranged mother, where she draws a portrait of her mother while her father and sister are out skiing. She says, looking back on it later: “I thought I was drawing Mum, but I was drawing myself, I thought I was studying Mum, but I was studying myself, so had I ultimately not got close to Mum or Mum’s world with my pencils but only my own?” And then, later, she says: “The relationship of a work of art to reality is uninteresting, the work’s relationship to the truth is crucial; the true value of the work doesn’t lie in its relationship to a so-called reality, but in its effect on the observer.” How has your relationship to “truth” evolved?

In the meeting of art and philosophy. Which constantly questions every so-called truth.

Besides, I think that Johanna expresses the relationship between art and truth very well in the quote above.

Johanna reflects on Carl Jung, who writes that man’s task is to develop consciousness. Then, several pages later, she says: “But what if the challenge is to reconcile yourself with the unresolved?” This sentence absolutely took my breath away. And it brings up something endemic to the literary industry in the U.S., the desire for resolution. What if we aren’t supposed to ever know the meaning behind a work?

I think that being able to pose a question clearly can be just as elucidating, decisive and liberating as providing an answer. And I believe that many of my books are more a case of articulating a question than providing clear answers to life’s inevitable conundrums — besides, are there ultimately any definitive answers to be found?