Interview Online

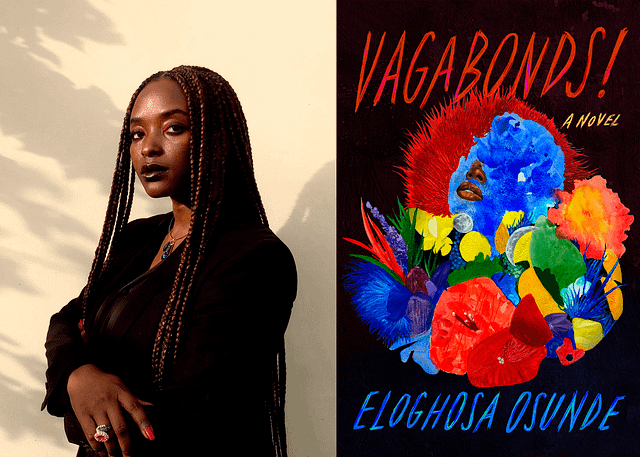

Eloghosa Osunde: On Our Own Terms

A conversation with the author of the novel Vagabonds!

By Logan February

The Lagos of Eloghosa Osunde’s Vagabonds! is highly surreal, and yet it feels true to my experience of the city. For me, Lagos will always be a place that quickens the pulse with its rush and violence, oceanic temptations, and cast of wildcard characters. In the novel, the streets are populated by embodied ghosts, unruly spirits, masked socialites — all survivors of the nation’s scoundrels-in-power. The story is presented within the frame narrative of Tatafo, an “eye” and underling of Lagos’ “cityspirit,” Èkó. Through Tatafo’s accounts, the city’s corrupt face is unveiled for the reader’s judgement. These revelations lead to rebellion, and Tatafo soon falls from grace into a community of outlaws: the queer, the poor, the undead, the variously vagabonded. The result is a defiant examination of the city’s glittering heart and diseased underside.

Lagos was where Osunde and I first met, in the lobby of a Radisson Blu Hotel during the Aké Arts & Book Festival in 2018. She was on her way out; we barely had a chance to say hello. The festival was showing her visual art series Obalende: The King Pursued Us Here. That work, much like Vagabonds!, was an entrancing exploration of place, community, and belonging. Upon discovering her writing through “Night Wind” — a darkly funny story which subverts the enduring Nigerian obsession with the notion of “the devil’s work” — I wrote to her expressing admiration for the story and requesting permission to use it in my teaching. Our dialogue as writers began then and continued online, as we read more of each other’s work and missed each other at other festivals, etc. Lagos, though not a very big city, easily kept our worlds apart. Her literary debut presents the occasion for us, at last, to discuss her stories, passions, and visions more intimately.

Much like Toni Morrison, Osunde spins her fiction from the shadows and scars of her characters, as much as from any goodness they possess. Vagabonds! is prefaced, in lieu of a traditional dedication, by this disclosure: “There are simple and good and straightforward and well-behaved people, I’m sure. But this is not a book about them.” True to these words, Osunde has crafted a book in which love overpowers taboo, and long-repressed truths about Nigerian identity hold the center.

Over the course of March, Osunde and I conversed in a shared document. I was writing from Lafayette, Indiana and Chicago, Illinois, while Osunde was in Abuja, Nigeria and Nairobi, Kenya. Our conversation touches on queerness, the mythic allures of Lagos, and the audacity of Vagabonds!

I was fortunate to read early chapters of this narrative over the years, but I’m curious to hear how the project came together from your point of view. How long was this book in the works, and what evolution did you notice in your creative process? Were you always writing within this one world of stories, or was Vagabonds!, as a novel, something you had to newly believe in as it all began to take shape?

I wrote “Night Wind” first, as a standalone short story in 2017. Something about that story revealed my sensibility as a writer — I learned what I like to see on a page. I leaned into the movement that is possible inside and between bodies, and I realized that things I believed as a child could be bent into new and comforting shapes. With that clarity, I wrote other short stories like “Grief Is the Gift” and “Rain.” I don’t think I realized I was writing this book. I just knew that the conversation happening between the stories was intentional and expansive, that characters still had things to say when I thought a story was over. I knew they were all connected, but it felt like wrestling with something vague and/or invisible — a process that tried to drive me mad — until 2019 when at work on a different novel entirely, I found the title. It quickly became clear to me where all the links were after that.

I don’t think of Vagabonds! as a novel exactly. I do think of it as a book but also as a trampoline, an endless site of possibilities, a playground, a container — a place where I fit together all the things I was interested in at the time and got to write as the chief conveyor of a particular world. It’s a place of imagination and beauty and storage and play.

Given this is such a strange and surreal work, it’s a lucky thing to hear how you describe it in your own words. Among the book’s many uncanny elements, I was especially interested in the subtle omnipresence of Tatafo, who filters in and out of the narrative. Tatafo is like an old imaginary friend, but more alive than ever, mediating the world of Vagabonds! You also seem to be subverting the idea of gossip, having Tatafo as the muse in this world of spirits. Of course, the word tatafo is a Nigerian pidgin slang that personifies gossip. As a storyteller — how would you describe your relationship to Tatafo, the blabbermouth?

I love Tatafo. I love the fact that he does exactly what he was created to do and that his character and actions are always in conversation with his name. He allows himself to really answer to that name, which is something I personally understand. I also enjoy his doggedness and that complete fixation on purpose. He’s completely unbothered by goodness as a concept and is more interested in efficiency, because he knows he was made to serve, to choose and move, to act — not to be accepted. I learn from the way he moves, how he looks at himself, even when he is ashamed.

Writing Tatafo, I was thinking a lot about the dynamic between the creator and the created. In the Bible, when God casts out Lucifer, we hear from God’s perspective, but we don’t get to hear what it would feel like to be a powerful spirit — God’s favorite angel — and then lose that link to the creator. What happens as a result, what madnesses can begin there? You won’t see that in the text; it is, after all, God’s book. But I find certain aspects of that story interesting — being unruly enough to move one’s creator to a specific kind of vengeance. A go-to-hell kind. And what happens when a spirit like that starts to roam? What do they do with their power once it leaves paradise? Tatafo knows what that feels like. And actually, he has a richer story than the creatorspirit, who can only estimate but never actually know what it is like to be outside their own grace; the other created, who remain obedient and so never find out what else exists outside where they worship; and even those who have always suffered, who were denied access to power from the start.

Outcasts and vagabonds know things the always-righteous and always-obedient cannot. But there’s someone who knows more than both the powerful and the disempowered and it’s whoever knows that power has endless sides, that it is never absolute, moves between entities like a shared dance. It’s only someone who knows from experience what it means to fall who can tell us what power actually is, because they have witnessed or used it in many ways. There’s a compassion that forms from that journey that is grounded in fact and actual lived-in context. That’s who Tatafo is: our door in.

I love your point about how compassion can come from a nuanced understanding of various perspectives. Vagabonds! gets at the psyche of power from many angles, always being both rigorous and tender. Another character with power, Wura Blackson, is revered by many as a master of her dressmaking craft. She is of infamous and insanely rich pedigree, but at times, despite a keen understanding of her privilege and ability, she finds herself under the power of these forces, unable to follow her true desires. Then Rain arrives, her fairygodgirl who changes everything. Why did Wura need to be liberated in this way?

Writing this story was an incredible process. I was visiting a friend in London and wrote the first draft at her place in two days. It was smooth and clear to me from the start. I think about death a lot, and for this story I was thinking about how freedom from the body is attainable if we die correctly, in alignment with ourselves — because when we’re aligned, we see our options, even in death.

Wura grew up around wealth and power, and experienced what bell hooks refers to as cathexis. But cathexis is not actual love — because love does not actively suppress you in the ways her family did. And there’s such a pain that comes from having misaligned definitions with people who love you. Her father thought freedom was money. Wura had money and learned that to her freedom meant something else. I love that even though she didn’t get that much time to practice it in life, she died freely, on her terms, after encountering Rain. I want to see more stories about people who got to the end of their lives and did whatever would impress their spirit, not whatever was required of them. Too many people die still worrying about how they look.

Earlier, you mentioned your interest in the possibilities of movement inside and between bodies. There’s a lot of physical and psychospiritual movement in Vagabonds!, and a great deal of restraint, too. Characters in “Grief is The Gift,” for instance, slip in and out of their bodies and lives like outfits. Yet there is unmistakable embodiment at other times. In a glamorously intimate moment on the dancefloor, the character Toju feels her body as a “soundsource.” I’m curious about this interplay — the withinness, betweenness, outsideness of bodies. This is my way of asking, also, what it was about that word vagabonds — a term used in Nigerian law to generalize the criminality of all queer-adjacent expressions — that brought the creative chaos all together.

When I came across the word vagabond in the context of the law, I understood it as a word meant to not just hurt but also condemn; a word employed to assist those who use it in defending brutal behavior and eventual sentencing. I also had the dictionary definition I grew up with in my mind. One of the synonyms that comes up often is outsider, or something close to that. And here’s the thing, some words offer immunity: there are certain socially agreed-upon words that if used on someone, will permit and excuse the most inhumane treatment. So sometimes, we run from certain words because we think the fight is won in using one’s life to say: it’s not true, I’m not a _____. But sometimes the fight is won in saying: that word is a descriptor and yes, even if I am that, I am still worthy of all my rights as a person.

At the time, I’d also been thinking a lot about the word queer, and what its reclamation has meant to me and for my life. There are so many things you can see better standing outside, and some of them will save your life. Language is never complete; it is always being made. We reinforce or skew meaning with usage and what I’ve realized over time is that I like to be an active participant in the definition of words designed to wound me. I am both stubborn and a force, so I do not answer simply because I am called. If I do, it’s because I know what that name means. Queer fits because I — and so many other people who decided the same thing — say so. Vagabond cannot be used to insult me, because I have already talked to that word, I have removed venom from its mouth; so, myself — and the readers who choose to use this word — will decide on other imaginative and empowering uses of this word, and it will, as a result, become more than the weapon it was set out to be; bigger than the people who placed it there. Like other words that were used to hurt but now have a new function, the moment vagabond is used differently, it is different.

This reminds me of the story, “There is Love at Home,” which is mostly set in The Secret Place — a woman-only sex club with an elite clientele. Although the club is a relatively safe space, it still has its limits. One of the workers, Divine, only fully reclaims who she is when she’s home with her love, Daisy. It’s not always easy for them, but there’s so much heart and humor in this story. I love this quote from the ending, where Daisy thanks her maker and her country for teaching them “how to rebel with both faith and sight.” How did you go about choosing and working with these characters, this reality of queer sex work in Nigeria? What did you learn from Daisy and Divine? Are there really such Secret Places?

“What did you learn from Daisy and Divine?” is such a perfect question, because they’re both smarter and braver than I am. I wrote that story from a deeply hopeful place, as a way of bringing that reality closer to myself. I wanted a story that talked about the private lives of queer sex workers in Nigeria, and I wanted to show that a love life is completely different from a sex life is completely different from a work life, even when that work includes sexual acts. In my relationship now, I can see how, even as the person who wrote that story, I have so much to learn. I borrow lessons from their love; I remember specific sections, I remember what they taught me about how much work it takes to heal and feel safe when your first life rejected you. I learn from them that it’s possible to have a tender relationship over time, and just have your respect for your partner deepen, as theirs does for you. Your final question is for the reader to answer for themselves.

Speaking of the reality of places, in the book you evoke Èkó as the mega-cityspirit of Lagos. Reading Èkó, I realized how much I miss and love Lagos, complicated as those feelings are for me. The arc of Vagabonds! goes from a total fear and reverence of Lagos to a deeper recognition of its people’s power and resilience. I was interested in this writing of Lagos as a force of spirit. Is this how you experience places in general? Why was it important for you to write this Lagos?

I know what you mean about complicated feelings. I still love Lagos. I always will. There really is no forgetting Lagos once it has happened to you, even if you leave. But there’s also the fact that I don’t think Lagos is just a place. I know that Lagos is a spirit and a massive unforgettable collaboration we all participate in. So, in writing this, I asked myself: what kind of spirit would Lagos be? To answer that question, I looked at how power moves in the city. The more power, the less you hear directly. You’ll find talking heads speaking on behalf of a force whose name you barely hear and whose face you don’t see. Lagos would never be the kind of spirit who moved alone, for instance, or in whose lap children could sit for comfort, or whose form anyone could describe for a fact. People have been trying for years, including me. What I know for sure is that the spirit is ancient and absolutely has a host of angels, a movement of minions. I also could see clearly that so much is delegated in Lagos specifically because Lagos is the kind of place that wants to trust you with more than you can handle, just so it can see how you do with that. It’s the kind of place to have a favorite and then become pissed off and punitive if the chosen ones cannot quite handle that weight. What you see in the book is one answer — my answer — to the question: what or who is Lagos? I wrote this Lagos because, to me, it is what’s true.

In “After God, Fear Women” — a fave title — the characters speculate that the ongoing exodus of women from the village, who vanish without explanation, may be related to events in a world beyond the story’s village, which one might interpret as a reference to the global #MeToo movement. But then, one character considers another possibility: “Wait, what if this is a new God?” — that power may be shifting hands in heaven, bringing a god with a heart for the othered, a transcendent god. Concerning justice — and gender — how do you feel about your fiction in the sense of these dual interfaces: the urgency of social and material reality, in tandem with those more timeless, mythical realities of spirit? As a poet, this interests me. I also know of many people who consider you a surrealist — do you see yourself as one?

For me, realms overlap. They’re not separate. To think about the body and its social implications, is also to think about the spirit, because that’s where we all begin. Not only are they not separate, but to pull one apart from the other feels both incorrect and incomplete to me. The picture isn’t full until it includes both.

Do I see myself as a surrealist? I can see why people use this label, but I don’t think about myself in categories. When I think about myself and my work, my priority is creating the thing I’m making with as much precision as possible. I want to be specifically myself in that making, I want the fingerprints on the work I make to be as mine as possible, and sometimes — ok fine, many times — that leans toward the surreal, because that’s where my mind is located. I enjoy surrealist art, but it’s not the root of my practice. People can call me whatever they want, is what I’m saying, as long as they’re engaging with the work thoroughly and honestly.

Last question: How different do you feel, with the novel now complete and out in the world?

I feel different now because I have blown my own mind with what I made. I have engaged with this work not just as a writer, but also as a reader who studies stories and their movement through the world. To trust my taste is to know that if I am impressed in my reading, then it is impressive. On top of that, I have made something that my friends love and some of my favorite writers respect. I’m taller as a result. Less tentative, more sure of what conversations I belong in. I also just respect myself so much more as a person, for surviving this book, for still being here. It’s a great place to be.