To read this story in Spanish, click here.

She came from the United States straight to my house in Buenos Aires — they didn’t want her in some hotel while they looked for an apartment to rent. My gringa cousin, Julie: she’d been born in Argentina, but when she was two, her parents — my aunt and uncle — had migrated to the States. They settled in Vermont: my uncle worked at Boeing, and my aunt — my dad’s sister — birthed children, decorated the house, and secretly held spiritist meetings in her beautiful, spacious living room. Rich blond Latinos of German heritage: their neighbors didn’t really know how to place them, since they came from South America but their last name was Meyer. Even so, their firstborn’s features betrayed the infiltrated strain of Native blood that came from my Indigenous grandmother: Julie had the dark dead eyes of a rat, untamable hair always standing on end, skin the color of wet sand. I’m pretty sure my aunt even started telling people she was adopted. My dad got so mad when he heard that rumor that he stopped writing and calling his sister for at least a year.

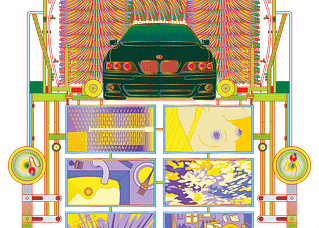

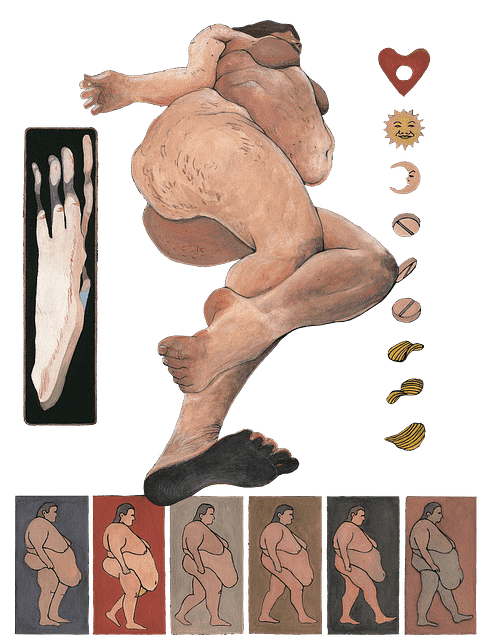

Though frequent, the communication with my gringo relatives was superficial. Photos taken in the snow. Those awful studio portraits Americans love so much, where they pose with big smiles, the sky-blue background of summer, Sunday clothes. Updates on their family achievements, all financial: a new car, trips to New York and Florida, college applications — only for the boys, though, Julie chose “other paths” — the little forest animals that came and ate up the garden, the constant renovation of bedrooms and kitchen. Of course, no one could be that happy and we knew full well they were lying, but we hardly cared. They lived far away in that other, rich world, and they never invited us to visit: they never said, “We’ll buy the tickets,” or, “Come spend the New Year in the snow.” It only proved how selfish and stingy they were. In the photos they sent, Julie always looked serious, badly dressed, and, to be honest, ugly. Fat. Bloated, maybe, with hair that was tangled and brittle. She looked gravely ill.

Julie was twenty-one — only a year older than me — when my aunt and uncle decided to bring her back to Argentina. There was a lot of yelling, first over the phone and later in our house, about whether or not to accept the visit, which threatened to be long. I still lived with my parents: I couldn’t find a good job, and I wasn’t making enough money to move out. Although a little run down, our house was big and comfortable, so space wasn’t the problem. The problem was that our gringo relatives had never done a thing to help us. They’d never sent us a single dollar. Never asked what we needed, and we had needed a whole lot during all the years of Argentina’s crisis, rebirth, loss, madness, disaster, and rebirth. Plus, my father had an ideological objection. Effectively, they were returning because Julie was sick, and they had spent a fortune on treatments in the United States. Apparently not everything was covered by the all-powerful Boeing health insurance. Or, more likely, my uncle wasn’t as high up in the company’s hierarchy as he liked to brag. “They’re coming so they can ransack this country’s health care system!” my dad bellowed. Mom didn’t try to soothe him, didn’t say, “But she’s your sister.” She let him slam the doors. She knew that in the end, we would take them in.

They arrived one rainy night in the middle of summer. I went to the airport with Dad. Julie was cross-eyed and obese, wearing a gray cotton sweat suit, and the plane ride had made her hands swell. I thought there was nothing to be done: there are people who just let themselves go, some people who just sink too deep, and one day they wake up crazy and monstrous. That’s how Julie was. Full-on abandonment. And we didn’t even know exactly what was wrong with her. My aunt had only cried over the phone. “Certain things can be discussed only in person, but it’s a mental problem. It’s mental.”

The arguments took place around the kitchen table. I was working and studying, so I didn’t see my parents or my gringo relatives much, but I never missed those nighttime showdowns. The gringos were crabby, for a whole bunch of reasons. They didn’t like the broken sidewalks, which weren’t really broken: sidewalks are uneven in Buenos Aires, the tree roots push them up, but whatever, my aunt and uncle had tripped over them. They didn’t trust the doctors they’d come to see, they were scandalized by the number of people living on the street — that complaint would set my father howling, “What about all the homeless people in New York!” And they didn’t like the food, they missed the cold and Nutella and the wide variety of yogurts in the grocery store. Julie barely spoke, though she was polite. She spent most of her time in her room. My aunt told us that Julie was schizophrenic and had gotten much worse in recent years. She didn’t want to give details. She’d never told us because she wanted a normal life for her daughter, she said.

They always wore workout clothes, all three of them. Cotton T-shirts and pants, sneakers, no makeup. “That’s how gringos dress around the house,” my dad said. “But they’re not gringos,” I insisted, and he ran a hand over my hair.

The discussions continued. “I don’t want her going to doctors at Moyano, that place is like a medieval asylum,” my uncle said. My mother, offended, informed them that she had been treated there for depression and that while it was true the facilities were somewhat shabby because the authorities neglected them, the professionals were of excellent quality. I stuck my nose in: “You all lived here,” I told them, “and not that long ago either. The Moyano has always been like that.” Everything looked decrepit to them, the royal family of Vermont. Meanwhile, Julie didn’t seem all that crazy, except for the way she ate: without stopping, using her hands, never taking a breath until the plate was empty. Then she would smile and down a half-liter of Coca-Cola. She was medicated, and surely that’s why she was so silent.

The big argument broke out one evening when the three of them came back from a consultation with a famous psychiatrist. They had been crying, clearly. They were also grumbling about how expensive the taxi had been, and on top of that it was an old car that stank of gasoline (they said gasolina like a movie dubbed in Mexico and not nafta like normal Argentines). When they came into the house, they ignored us. I had the day off, and my parents had just gotten home from work — it must have been six or so.

“It’s your fault,” my uncle yelled at my aunt, in English. “It’s all your fault, you and your damned Ouija board!”

My dad broke in to say that in this house, we speak Spanish. “You are my guests. You’re my sister. You’re Argentine, goddamn it!”

They looked at him disconcertedly, and I saw my aunt break down. I noticed the gray hairs sprouting from her scalp, her crooked glasses, the wrinkles at the sides of her mouth like vertical cuts or ritual decorations. “That wasn’t it,” she said, “it couldn’t be that, it was only a game.”

“Enough with the mystery,” my dad said. He stood up, crossed his arms, and demanded to know the story. And my aunt told him, crying like a baby all the while. Julie was right there, silent but clearly affected. My uncle stared down at the floor, and at a certain point, when the account of Julie’s madness reached the level of indecency, he had to go out to the patio.

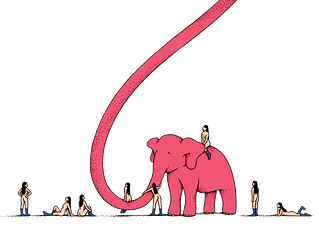

The story wasn’t all that complicated — it was even a horror movie cliché. When she was little, Julie had started to play with an invisible friend, and then with several. They lasted too long: she was fourteen years old and still talking to these friends. Eventually she told my aunt that they had come to the house during those sessions of spiritism and Ouija she’d held in the house for years, like social gatherings. Gatherings that came to a stop immediately after that revelation, and it was decreed that the “voices” had nothing to do with ghosts and everything to do with Julie’s schizophrenia, intensified by problems at school that made it necessary for her to be homeschooled. (Julie had zero possibility of surviving high school with her looks, not in the United States or anywhere else.) All the friends-spirits-voices did was talk to her, they didn’t do anything like make sinister suggestions, break things, or make noise like poltergeists. It was easy to live with them, and with Julie. Yes, it was a little creepy to hear her talk and laugh and sometimes cry with nobody there, but if that was going to be it then fine, it was compatible with a normal life. What about her brothers? They were already off at college. Luckily, they had missed the worst and most recent phase of her illness.

My aunt had caught Julie having sex with the spirits. My mother choked on her wine when she heard that, and she spat a mouthful onto the table: it looked like watered-down blood on the white Formica. My dad peered diffidently at Julie, and she met his gaze unabashed. That’s when my uncle left. “I don’t know how she does it,” my aunt went on, now without shame, naked, relieved. “She masturbates, sure, but it’s not normal masturbation. If only you could see it: there are finger marks on her body. There are hands that squeeze her breasts! Invisible hands!”

She started to cry again. Just to say something, I told them it reminded me of the movie The Entity. Julie spoke then. Her Spanish was neutral but perfect.

“This is different. In that movie, the protagonist is raped. I like what they do to me. They’re the only ones who want me.”

She didn’t storm out or join in her mother’s sobbing. She merely opened a bag of chips and started eating them the way she ate everything: with both hands, the salt and grease coating her lips.

“The doctors say it’s possible,” said my aunt as she dabbed her face with a tissue, “that sometimes the mind can exert such great power over the body that it produces inexplicable reactions.”

“Like psychosomatic events,” my mom interrupted, and she started talking about her depression and her ulcerative colitis, the bloody diarrhea, the asthma that had appeared and vanished out of the blue. I don’t like to remember my mom’s depression: it was postpartum and I think it was my fault. Well, I know it was. I caused it — intent is irrelevant.

Julie finished the chips, shook her head, and assured us that all the pills and treatments in the world weren’t going to cure her, because there was nothing to cure. “I like it,” she said. “I don’t know why it’s a problem.”

“Oh, you don’t know?” shouted my aunt, and she snatched the empty chip bag from Julie’s hands. Julie wiped her greasy hands on our sofa. Our sofas were pretty dirty anyway.

“I don’t know,” Julie said. And in English she added that her life would be normal if it weren’t for the medication, the pills that made her fat and deformed. “I turned into a monster,” she said. “But they want me anyway.”

My uncle came back in. He listened as Julie told us, in English, about the joy of those ghost fingers, how they weren’t cold at all, how they were pure pleasure. He slapped her so hard her mouth swelled up immediately, though there was no blood. And he called her a whore. She was used to it, she just picked up her phone and went to her room — she was never without her phone. We all sat there trembling. My aunt pretended to faint, I think so we would stop picturing her obese daughter, her rolls of fat fondled lustfully, lovingly, by hands from beyond the grave.

Three weeks in, they threatened to leave: not to go back to the U.S. — no one had asked about the status of my uncle’s job at Boeing, and they didn’t bring it up — but to rent an apartment and “get out of our hair.” Mom asked them to stay, out of politeness, and they, rude as ever, said thanks very much and never mentioned leaving again.

“They’re stone broke,” my dad said through clenched teeth as he watered the plants in our garden. Out of pure rage he soaked the cat, who ran to hide behind the big fern, indignant. “They brought her here because they can’t pay for treatment there. Psychiatry is really expensive in Yankeeland, and the exchange rate works for them here. Plus, we have better mental health professionals. They don’t know anything in the U.S. They just load you up with drugs, end of story.”

Still, he wouldn’t kick them out. They were his family, after all, and Julie always locked the door to her room. If she was having ghost sex in there, she was very discreet about it. She had started a new treatment that meant she was hospitalized for half the day and was on more medication. She came back half asleep, and she grew paler and fatter. I felt really bad for her, but I didn’t know what to do. My uncle went to bed drunk. My aunt spent all her time on Skype with her gringa girlfriends and sometimes with my cousins, who were friendly enough but seemed very uninterested. I understood: what a relief to get Julie and their parents off their backs and so far away.

Sometimes, before I left for class, Julie and I had breakfast together on the patio. It was fall, the days were beautiful, and she ate a little more decently, maybe imitating me. She still spilled on herself, but it wasn’t her fault. It was the medication that made her shake. I started to like my cousin. She had dignity, and she didn’t back down. I listened to her parents fighting in English — they assumed we didn’t understand — because the doctors couldn’t convince her that her spirit lovers didn’t exist. She was sure they did, and she felt loved. Why take that away from her? I’d see her on the patio before she left for the hospital, looking at the plants or smiling at the cat, and every morning, as she gobbled her cereal and I drank my coffee, I tried to find a solution for her, one that would set her free and get my aunt and uncle out of the house. Plus, from listening to those conversations — those arguments — I had found out that they wanted to commit her. To leave her in Argentina. Go back to America without the crazy daughter who came off so badly at parties. Not so much because of her sex with spirits — that could be kept a secret — but because her condition kept them from planning trips to Florida, or maybe moving to a new house, perhaps one overlooking a lake. They were ashamed of how she looked. They were going to abandon her. They couldn’t pay for an institution in the United States, but here, they could place her in a public hospital for free. Julie was Argentine, after all. And who would be left to visit her? My parents? Me?

There had to be other people like her. I don’t know if I believed her or not: that was beside the point. I didn’t say a word to my parents or to Julie or to anyone: not even my friends knew about her situation. I dived into the internet. There had to be other people who had sex with spirits and they must get together, hopefully in a community that wasn’t anonymous or only online. There were people who shared their fetishes for statues and mannequins, even stuffed animals. There were men who had sex dressed as babies, and women addicted to plastic, and men and women who got turned on by licking eyeballs.

But sex with ghosts didn’t turn out to be so easy to find. Julie let herself be loved by the invisible dead, her deal had nothing to do with the human body, hot or cold. At first, the closest I could find were the necrophiliacs constantly complaining about how they couldn’t even get close to an open casket. Reading all their filth, I started to appreciate Julie’s elegance. The grace in her rejection of all her parents’ hopeless vulgarity. In how she had ruined her body until it was grotesque in demonstration of the fact that even so, it was beautiful in a place that we couldn’t reach and she could. Did I admire her? I don’t know. I envied her a little, though I didn’t want that kind of abandonment for myself. Nor did I want to be her caretaker.

After a week of intense searching, when I was ready to give up — a week of online searches is really long, too much — I found a group in the United States called the Marjorie Simmons Association. I had to pay a fee and write a note requesting admission and then wait for the administrators to reply, but one morning I found the “Congratulations” email in my inbox. And that same night I chatted with a woman named Melinda and told her all about my problem. Our problem. She wanted to know why Julie wasn’t speaking for herself, and I explained that she was very drugged. Melinda understood: “They always pathologize us,” she told me. Without a word to Julie, I arranged a meeting with Melinda for the next day. Over Skype, but just a voice call: we didn’t have enough trust to look each other in the eyes.

When I told my cousin, she started to tremble even more. I spoke a little in English and a little in Spanish, even though I knew perfectly well that she understood me in our language. I never got to the end of my explanation. She threw her breakfast to the floor, took three fat strides over to me, and hugged me with true gratitude. Strange: she smelled really good. In spite of her coarseness and her clumsiness with food, she was scrupulously clean. Did she prepare herself for her lovers? I met her eyes.

“Why didn’t you look for them yourself?” I wanted to know. “You always have your phone, you’re always online.”

“I don’t know,” she said sincerely. “I was afraid. Other people like me? People scare me.”

“Then are you going to be afraid tonight? Should I cancel the call?”

“No,” she told me, her eyes round, waving her chubby fingers. “They want to lock me up. Did you know?”

I knew.

“You have to get away,” I told her.

Julie nodded.

On the ferry that took us to Uruguay, Julie was so happy she didn’t even care about the disapproving looks from skinny women who were crossing the Río de la Plata to spend a weekend in Colonia. We had escaped just in time, with the family shitstorm well underway. My uncle had already gone back to the United States, and now my aunt was announcing her departure as well, weepy, whiny, so utterly false it was outrageous. She had found a very good hospital for Julie, she said, and she swore up and down she would pay for it. “As if I wouldn’t pay for my very own daughter,” she yelled. My father, cruel and certain at the same time, called up the clinic and put the phone on speaker so we could all hear, and he made us listen as the accountant told us that yes, they had an admittance date for the patient, but they hadn’t received a deposit. My father hung up, and my aunt, spitting mad, screamed that she was not going to condemn herself to spend what remained of her life with that monster, and if it really had been her fault, if it was her spiritist sessions that had brought about this disgrace, well, she wasn’t planning to carry that guilt around either. I didn’t hear that shouting match myself, I was working, but Julie told me all about it. Since that first talk with Melinda, she’d made great strides: they were friends now. They had forbidden me from taking part in their meetings and I agreed, even though I was curious. I understood.

It turned out that it wasn’t only women who were “visited by spirits” — that’s how they put it — there were many men who were visited as well. And it turned out that they had their own community, headquartered in the United States: they lived in a trailer park in Arizona. The association was named after a widow, Marjorie Simmons, who had managed to have sex with the spirit of her dead husband. There weren’t many like Marjorie, but Melinda promised Julie that if she wanted, she could find out the identities of the spirits who visited her. If she didn’t want to, they would remain anonymous. She had total freedom. The problem was that the association didn’t have any branches in Argentina. “Our one small community in South America is in Uruguay.” Her pronunciation of the country was awful, and it was even more stupidly awful that this Melinda didn’t know that Uruguay is right across the river from Buenos Aires, but I never thought that her ignorance meant she or her association were fraudulent. She was a gringa: that’s how they are. They don’t know anything about the world, they’re incapable of figuring things out, they never think to look at a map. Julie agreed with me. “That is how they are,” she admitted.

Melinda helped Julie organize her admission to the Uruguayan community. It was on the outskirts of a town near Colonia, Nueva Helvecia, the Swiss colony. That place was famous for its New Age retreats and communities that practiced alternative spirituality. That made sense. It was a good place to hide.

Julie was a little afraid of the ship, I realized. We had taken the first ferry of the morning, bright and early: we left right after our usual breakfast ritual. I could come back that same day: no one would even notice I was gone. She wasn’t at all scared, though, when she crossed the border with her American passport, or when she rented a car and gave a fake name. She knew how to cover her tracks. Perhaps Melinda had given her instructions? I drove. Nueva Helvecia was very close, only sixty kilometers from Colonia. Julie was still taking her pills; Melinda had explained that the community would be able to help her through withdrawal. We had the coordinates, the description of the house we were looking for, and a name: Rolf. I’m sure it wasn’t real. It’s so easy to disappear, I thought. All you need is determination, and not that much of it, plus someone you can trust and a little money. Julie had stolen five hundred dollars from her mother. That was enough to start, they didn’t ask for more. They were self-sufficient: they had a farm and received donations. Also, they lived on land that was owned by one of the members. A rich Uruguayan. I don’t know if he was visited by spirits or was just a morbid benefactor.

Julie talked a lot on the short trip there: an hour on the ferry, another by car. She told me about her first visitations, about the differences between her visitors, about one who especially liked to lick her asshole. She said it just like that, so savage, and I almost felt dizzy: she was losing her elegance. Or maybe she really was crazy. Now I’d never know. I told her to be quiet, that I was worried about getting lost, and she complied but was clearly irked. I did not know her, I realized. Maybe her parents, as stingy and gringo and unpleasant as they were, had been telling the truth. Maybe they had heard her talk this explicitly, unchecked, and they’d had enough. Maybe they had taught her how to behave in public, with help from the pills. What if I’d made a mistake?

We reached the house. It was pretty but looked sort of abandoned. The silence was broken by the clucking of chickens. Rolf was waiting for us, dressed all in white. He was tall and gray-haired and wore black glasses. He could, of course, have been a murderer. My cousin threw herself into his arms and then into mine. Leaning against the car, I lit a cigarette and offered one to Rolf, who declined. He talked to Julie, welcoming her. I handed her the bag: she was hopping up and down like a little kid, her enormous ass (the same one the spirits ate out so well) bouncing around as if it were full of water. I put on my sunglasses: the sun was too bright. Rolf thanked me and then said, in a pure Uruguayan accent that betrayed his fake name, “This is as far as you go.”

“Will you take good care of her?” I asked.

Rolf smiled at me. His teeth were perfect, very white and well cared for.

“Of course,” he said. “And you can always visit her.”

Julie gave me another kiss on the cheek and then left. Rolf carried her bag while she talked nonstop. I realized what was going to happen.

I would go home. I’d pretend to know nothing about Julie’s whereabouts. They’d look for her for a time. We’d report her as missing. Her brothers would come; her father would return. She’d be given up for dead. And I would come back to Nueva Helvecia and I’d never find the pretty but abandoned house, I’d never again see Rolf’s teeth or my cousin’s bulging ass walking away down a dry dirt path, under the sun, heading off to meet the other people who were just like her.