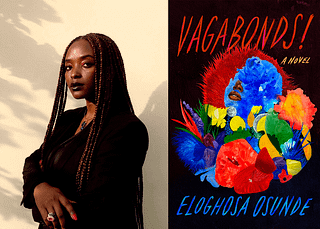

Celia Paul is a rare artist. One of Britain’s most important contemporary painters, she is also the author of two books that have garnered glowing praise. Paul’s first book, the memoir Self-Portrait (2019), recounted her time as a young painter at the Slade School of Fine Art, where she was “discovered” by the painter Lucian Freud, then a visiting professor and nearly forty years her senior. They became lovers. She sat for him. They had a child together, which introduced Paul to the injustices inherent in motherhood — its paradoxes, its impossible choices. How to turn away from her work, the very thing that offered space to live and breathe, and toward motherhood, a kind of mythological ensnarement? Desire and ambition, endurance and betrayal, how to reconcile love with loneliness. These are central themes in her art and writing.

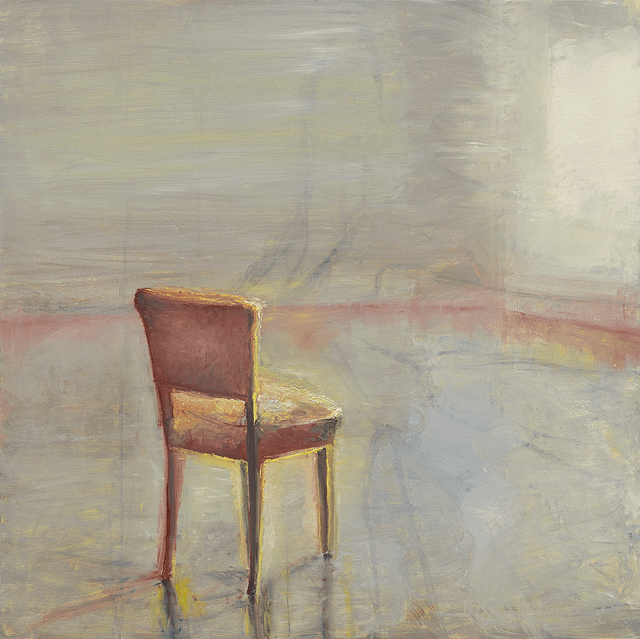

The daughter of Christian missionaries, Paul spent the beginning of her childhood in Kerala, India, before moving to England. She now resides in an austere London studio where she works and sleeps. She has few belongings, even fewer comforts, and devotes herself entirely to her work. She recently lost her beloved husband, Steven, to cancer. They did not live together. In her house there is little more than her paintings, her paints, a chair, and a bed. Her walls are bare. Her method depends on cultivating an inner life. To go inward, Paul believes, is to burrow into truth. In the quiet is where life’s meaning resides.

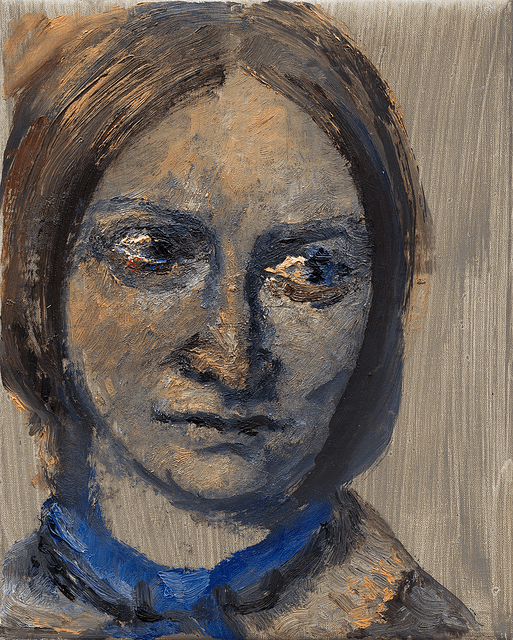

Paul’s most recent book, Letters to Gwen John, released this spring, is a speculative correspondence with the British painter Gwen John, who died in 1939, twenty years before Paul was born. It is a loving and inquiring text, a lyrical correspondence between two women filtered through the inner life of one. It is also an intimate cataloguing of how loneliness and desire transmute to artistic awakening. Gwen John and Celia Paul share similarities. Both are transcendent painters. Both were muses of renowned and notorious artists, men who belittled them, men they devoted much of their lives to, men who were celebrated as geniuses. John had been in a relationship with the sculptor and painter Auguste Rodin; she sat for him endlessly, in painful poses.

Paul and I began this interview by email in May to discuss Letters to Gwen John, but our exchange, which continued for over a month, often extended into broader questions about artmaking and how to live now. It has been an honor to correspond with and learn from Paul; she is a generous person with an unlimited well of kindness and humility.

I can’t help but think of Gwen John as a kind of doppelgänger, your twin from across time through whom you can project another possible experience of yourself. Can you describe your impulse with this book? Is John your model? Are you inhabiting the role of artist, with John as muse?

By writing to Gwen, I want to get to know her and to know myself better through her — like when you meet someone and you feel a deep connection from the start, so that it becomes a mutual revelation of innermost thoughts and desires, spoken and unspoken. It’s not about me being an artist and her my muse, or vice versa, or about power or appropriation; more like a recognition, an encounter, which can lead to newness and inspiration. She grows more and more in focus: the timbre of her voice at one with the colors of the paint she uses; her subtlety and, at times, a whimsicality that irritates me and makes me realize that I am much harsher than her. Where she always chooses beauty, I often choose pain — as in her avoidance of old age as a subject, whereas, for me, old age reveals riches beyond beauty. In turn, I sense that, without acrimony, she defends her love of youth and beauty and innocence.

Gwen often felt misunderstood by Augustus, her brother. He thought it was unnatural to choose solitude and self-denial above loving companionship. His insistence on the perversity of her choice disturbed her and made her both ashamed and stubborn. I share these feelings of shame — my own choice of solitude can seem consciously wayward if I look at myself from an outside perspective — yet I know it’s the only way I can single-mindedly paint as I want to.

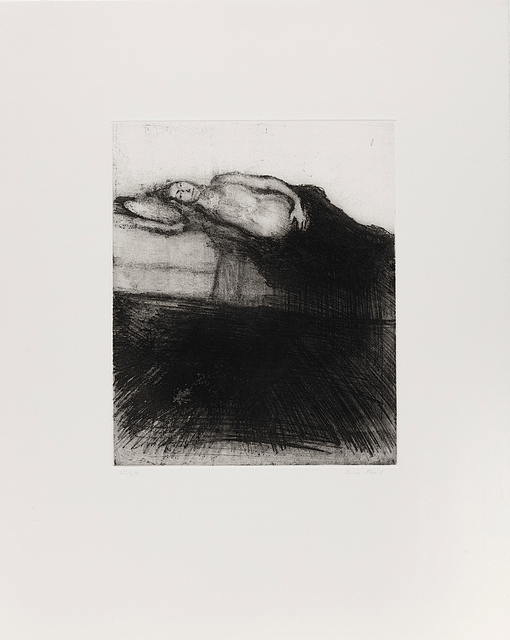

Gwen was able to channel her emotion into her art even at times of extreme mental turbulence. Her delicate brush marks show no trace of the turmoil of her heart, yet the paintings are charged with feeling, full to the brim with poised, reined-in passion. So Gwen is not only a confidante but a precedent. I am comforted by her and feel more at home in the world because of her.

You’ve talked about making space for creative work as a kind of sacred removal, a necessary inner silence that is cultivated both internally and externally. This life of solitude could be misinterpreted as cold, or stark. And yet your work — and John’s — is nothing of the sort. It pulses with feeling. The idea of old age revealing riches beyond beauty seems so transgressive, at least in the West. It reminds me of when I saw you speak at your U.S. book launch for Letters to Gwen John; you glowed with a shimmering radiance, seated in front of a stark, white wall. It was your innerness. I was very moved by your energy. Do you think this energy is what makes art feel alive and true?

I think the inner energy of each artist is particular to them and somehow makes their art alive and unique to them. This energy is mysterious. In the case of painting, the energy is mostly lost in reproduction. You really need to stand in front of a painting to experience it. Gwen’s energy glowed steadily throughout her life until the end. Now that the book is out in the world, and as I approach the age when Gwen died, I have been considering my own energy in relation to hers and realize that mine has burned much more fitfully. It has been like a fire that has sometimes burned too low, with sudden flares. As I approach old age my energy is burning brighter. I need to guard it now. I battle with insomnia — it’s actually nearly two in the morning in London as I’m writing this to you, Makenna — because I feel almost too intensely alive and everything is almost too heightened and beautiful. The aloneness I feel is very intense, too, and sometimes very painful, but I don’t want to swap it for the comfort of companionship in case I subdue the intensity of my experience.

In the morning I’m starting a painting of peonies — white peonies with a subtle pink glow — so I’ll say goodnight!

I want to know how you begin a painting, the first brushstroke, where it lands. But back to what you said about the energy of the artist coming through a painting — it makes me think of a book, which unlike a painting is a medium that depends on being reproduced and held individually. How does writing a book differ, for you, from painting? Do you feel you have the same energy when you write?

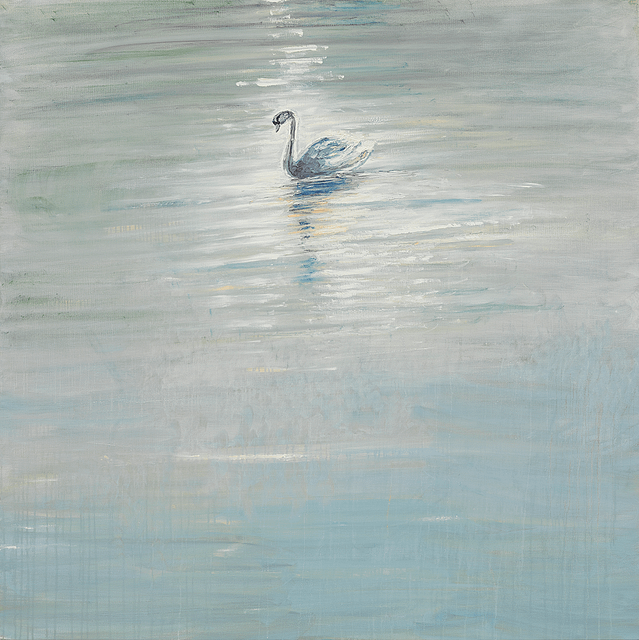

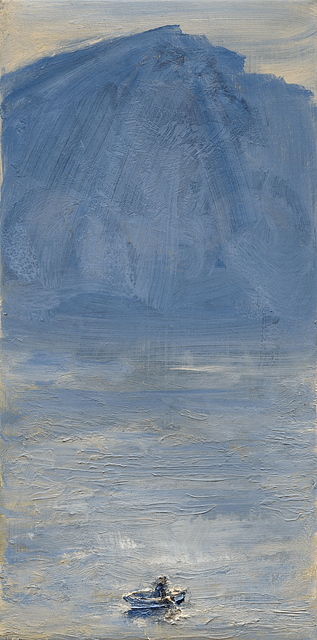

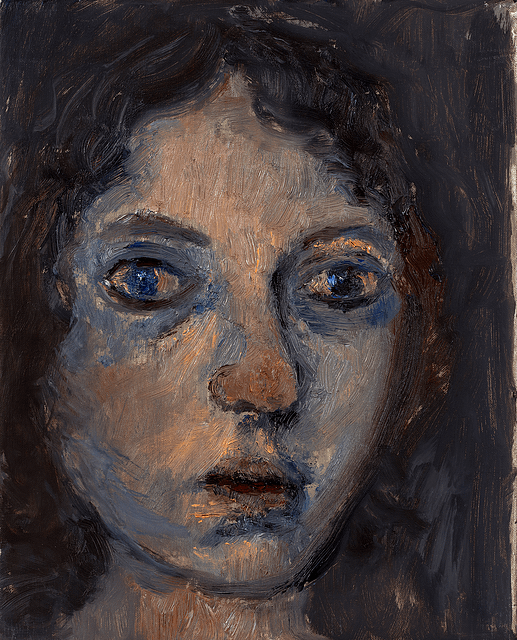

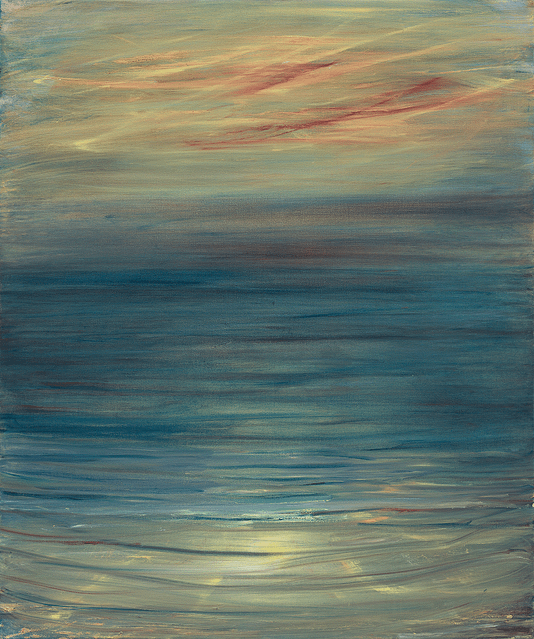

When I start a painting, I need to know it’s what I want to do — that the subject corresponds to my need of the time. Often I work on a series of paintings around a theme which then leads on to another series: my seascapes have recently been replaced by flowers, and I now can’t paint seascapes for the time-being. Throughout I have painted self-portraits as a way of identifying where I am emotionally.

As you say, a book depends on being reproduced and held individually — the opposite to a painting which is often, though not always, diminished by reproduction and is there on the wall, forever open. Part of the pleasure of reading is that fact of holding the object in your hand, the privacy of the text, the words addressed to you alone. There’s a purity in the democracy of a book — that it is easily available to everyone. And affordable. The whole question about money in relation to the art world, and therefore the inaccessibility of a lot of art, makes painting literature’s opposite in many ways. In my books I have integrated images — John’s paintings and my own — and though, as reproductions, they only indicate the original, there is a particular delight in seeing them interwoven with the text, like seeing friends in a crowded room.

When I write, I think. When I paint, I don’t think — or not in the same exacting way. The act of painting is like the act of prayer, for me. I depend on grace. I need to still myself and allow myself to be guided. When I write I am definitely the one holding the reins. The energy in the writing process has a different quality for this reason — more like a searchlight than a fire.

The quietness you speak of I also seek, and yet I sometimes feel I have no right to it. It is likely because of my children, who, perhaps rightly, assume I am always there for the taking. I am grateful for my husband, who I jokingly call my muse, as I find endless inspiration in him, the way he lives his life, so true to his own center, so uninterested in the world’s opinion. And just now, I reread your acknowledgements in Letters to Gwen John and cried when you spoke of your husband Steve’s last days. I think I could never survive it.

Quietness is so necessary. We should be entitled to it naturally, but it is a battle to gain it. The best quietness is when you are surrounded by loved ones and they are allowing you the aloneness — rather than full-blown aloneness. I wish everything wasn’t all or nothing. Your husband sounds a rarity, a treasure. My husband shared that insouciance about the world’s opinion. It’s tremendously reassuring. Such a contrast to Lucian and other men I have been involved with who have been in competition with me and possessive of me as an artist rather than loving me for myself. My husband loved me for myself — which of course includes myself the artist — and I must be grateful I had this. Not many women do. But my goodness, life is strange without him.

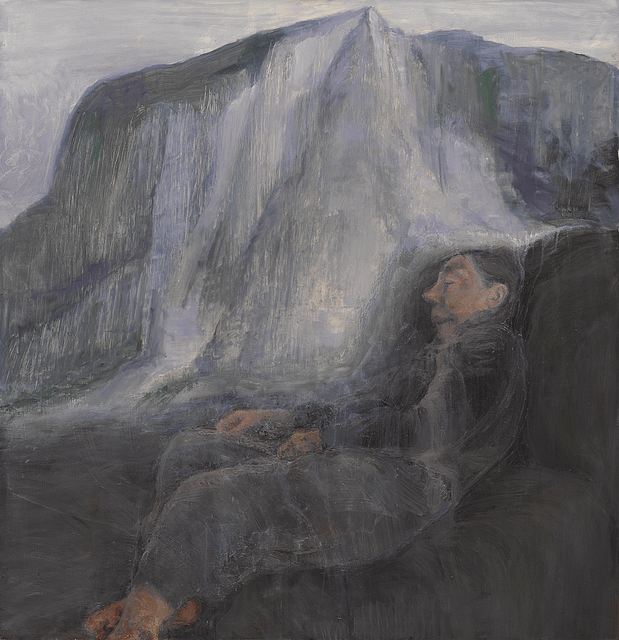

You’ve said that your writing is something your mother would have been happy about, that, as you write, “she was more at home with words than with images.” She was one of your most committed sitters. In Letters to Gwen John you describe a particular painting, My Mother and the Mountain (1994-2020), which is a painting with an arresting sense of loss. Her mouth is almost childlike, her body position so vulnerable, as if either death or the return of infancy are about to visit her, as an angel, in sleep. You write that you always longed for your mother’s attention. Do you think in some way, through this prolonged encounter with John, you are communicating with her?

I am very interested by this question. I do think it’s an uncanny coincidence that I started writing only after my mother’s death and that in some way her death liberated me into the language of words. I often wonder about it. She needed my attention when she was alive. She gave herself up to the experience of sitting for me because I think she felt deprived of real attention during her own life: widowed young, with five demanding daughters. She was not a good listener, often anxious and preoccupied. She was proud of me as an artist, but literature is what counted for her. I hope she wouldn’t feel competitive with me as a writer since that is really what she wanted to do. My voice is different to hers — more tempered. I needed to write in order to get her attention. She didn’t listen to me in ordinary conversation, but I know she would seriously listen to my writing self.

It is an intense time for me — the grieving — and it means a lot that you understand. It is inspiring to be in touch.

For me as well, Celia. I want to go back to something you said earlier, that men in your past, particularly Lucian Freud, were in competition with you, seeking to control you as a possession. To be in competition implies a threat of losing one’s power — they must have seen in you the innerness they could not summon, a kind of genius they wanted to obtain but could not fully manifest themselves. It makes me think of a book called Witches, Midwives, and Nurses (2010), an inquiry into the demonization of women healers and the sociopolitical, economic monopolization of medicine, tracking the roots of medical school as created for men only, with women healers — those who weren’t burned at the stake — limited to the role of nurse. This feels similar to the idea of a male artist and his female muse. And how transgressive for you, in the context of this system, to finally be the one in full power.

I have been puzzled and hurt that I often inspire competitiveness in the men that I have loved — most especially in the case of Lucian Freud. His rivalry communicated itself to me as anger, which frightened me. As I withdrew from him, he became more possessive. I needed to withdraw in order to create. His scrutiny felt intrusive at times and unsettled me. But I loved him and wanted him to love me. It was my talent that attracted him to me in the first place and why he felt connected to me, but I became tangled about my ambition. I am interested in your analogy of the medieval woman healer being regarded with fear and suspicion. It can create a feeling of shame in a woman if she clings on to her uncanny powers: she can become alienated and undesired. There is no place for her except of her own making. It is easier to fit in, easier to be a muse than to be the artist — that way you can remain cherished.

It does feel transgressive to be finally in power and it is liberating. But it has come at a cost. I have never wanted to have a happy domestic life with anyone — that has never been an aim. I am certain that, even if I hadn’t been involved with Lucian from when I was very young, I wouldn’t have desired to share my daily life with someone. Maybe because I spent much of my childhood living in communities. My father was a missionary in India where I was born. My first home was part of the complex of the theological seminary in Kerala. Later, my father was warden of an evangelical community on the North Devon coast where we, as a family, shared all our meals with the community. I desperately desired solitude. My burning ambition was privacy. So in this way, Lucian suited me because he also desired privacy and separateness. My husband Steven Kupfer and I lived separately, too, and let each other be completely free. Yet we were always there for each other. So the power that I now have to live my life in freedom to create has, since Steven’s death, come at the price of sometimes overwhelming solitude.

To be cherished is such a fundamental human desire. To have Lucian see your paintings and acknowledge your talent as he neared the end of his life, as you write about in the book, is as if his cherishing of you could finally be pure, perhaps letting go of ego in death. How do we cherish each other, as artists? Can we cherish what challenges us?

I have found a place more readily open to me as a writer. In my own experience, to be a woman painter is to be separate. There is no communality in the language of painting, for women. Our identity is defined by the use of our medium — our paint — which remains unique to us and isolates us.

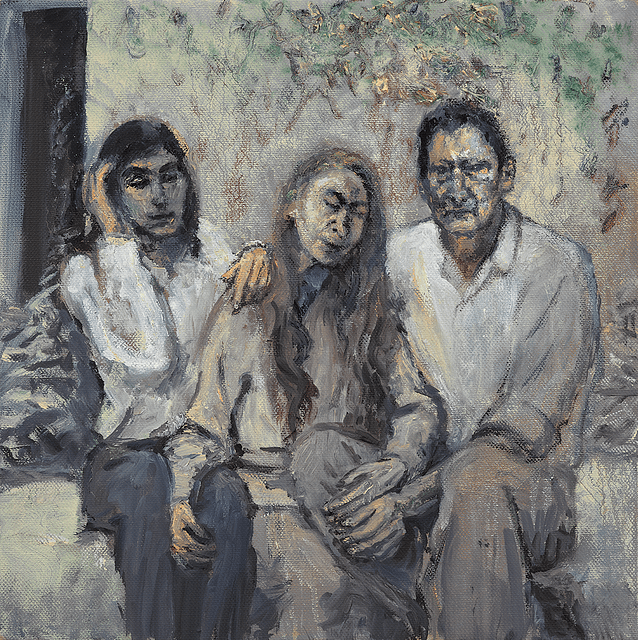

There is a famous photograph by John Deakin taken in 1963 of the most celebrated painters in London at the time: Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, Michael Andrews. They are in animated conversation with each other. They are obviously discussing art. They are showing off, and there is definitely rivalry, but they are being inspired by each other, too. I am often associated with the School of London, which is predominantly male, so I find it hard to imagine a group of women painters united by a similarly electric dynamic. I have no female friends who are painters. I have acquaintances who I admire and even feel close to: Paula Rego, for instance. Yet there is a boundary that must not be crossed. Paula doesn’t visit my studio and I don’t visit hers.* If Gwen John and I knew each other in real life, we might well keep our distance. It has been exciting to me — through the world of writing — to be sharing ideas with women writers, like yourself, Makenna.

Male painters are unashamedly competitive, mainly with other male painters but, in Lucian’s case, he was challenged by female painters too; he was particularly disparaging of their ambition if he considered it to be disproportionate to their talent.

When I started to go my own way by allowing my more visionary view of the world to guide my art, as opposed to Lucian’s strictly existential view, he felt he had lost control of me; his lack of control disturbed him and unsettled the loving balance between us. I no longer felt cherished.

In the last years of his life he was supportive of me and acknowledged my talent. That meant a lot to me. I think you are right that as he started to slip out of this world, he let go of his ego and that helped him to love me as separate from himself.

And thank goodness for your visionary view of the world, as juxtaposed to Lucian’s existentialist one. I wonder how many artists feel their true spirit is misunderstood by those who consume it, or seek to obtain it. The connection with women writers that you speak of seems to summon a transformative energy, one that is richly alive in your book. You write about transformation toward the end of Letters to Gwen John, a future fire that you mention in a kind of prophecy: “I don’t know how this fire will present itself to me, or in what form, but I am certain of it — as certain as when in a train one is made aware, through the change in air pressure, that one is approaching a tunnel.” Has the fire happened yet?

I suppose the reference to a transforming fire has a mystical reference — purification through fire. It is part of the religious language that I was brought up on. It connects to images — sometimes very specifically. The burning bracken fields around the religious community where I grew up is one image that recurs. I think they burnt the old bracken in autumn so that the new bracken would be healthier, stronger. I had a sense, before the pandemic, that something was about to happen, some profound change. I titled the painting I finished of my sister Kate in February 2020 Last Kate in White; I had done a long series of portraits of her in a white dress. I said to her that I would paint her again in a year’s time and she should wear a different color then because everything would be different. In fact it was eighteen months before I could paint her again — due to lockdown restrictions. She arrived wearing a rust-red silk blouse and a brown skirt — the colors of autumn. Between the finishing of the last painting and the start of the new there had been the pandemic and my husband had died. Those events were my personal transforming fire, so Kate’s fiery clothes seemed to visually fulfill this prophecy. I am still dealing with the impact on my life of the transforming fire, and I am considering what direction my life should take. Whether to follow Gwen’s absolute asceticism or whether to go for something more engaged with life. So I am still at the stage of the new bracken shoots after the fire has cooled. Whether to be gilded by winter frost or to wait for spring and slowly unfurl.

Do you think it would be possible to live a life of asceticism and of engagement? Or is the choice between them an imperative?

The ideal would be to live a life where asceticism and engagement went hand in hand. For me, I am more drawn to asceticism; engagement would be much more challenging. Gwen John wrote, “You make your life let it be consciously, with fearlessness.” I want the choices I make from now on to be my own choices, not imposed choices.

I wrote Letters to Gwen John because I needed to explore the kind of painter I am. There were some questions left unanswered in Self-Portrait. Is self-denial necessarily victimhood? Lucian Freud has been described repeatedly as a misogynist; but then the public image of him is also of a womanizer — people never stop going on about how many lovers he had, and countless children by many different women. He was a successful lover, in the world’s eyes. What does that say about the innumerable women who fell in love with him? If he is a misogynist, then a lot of women must be self-hating. I fell in love with him, and I have also battled with self-hatred.

I wanted to look at myself more closely. It helped me to see myself in relation to Gwen John whose involvement with Auguste Rodin seemed to bear so many comparisons to my own experience. Rodin, like Freud, is almost as famous as a lover as he is as an artist. How did Gwen and I turn our submissiveness into strength so that our passivity became for both of us the powerful fuel that drives our highly charged art?

I see that it is healthier and better to find equality in love, so that each lover is free. In writing Letters to Gwen John, I deliberately confronted my bondage, hoping that the confrontation would free me. By successfully capturing Lucian in the painting I did of him — which I describe towards the end of the book — I gain power over him, and I feel more free as a result.

It’s hard to end a conversation that feels like it could be never ending. I’m curious about what you hope for yourself, or for the world, in the coming year.

I don’t as yet have any plans to do more writing, but I haven’t ruled it out as a possibility. I am excited to be painting on a bigger scale. I feel energized. I hope my energy — which always ebbs and flows — will last so that I can complete some large paintings that I have in my mind. I want to paint figures in landscapes — portraits of people, rather, in portraits of landscapes.

There are a number of things I need to settle in my life. I have a sense of urgency. Please God that the world will become freer, more equal. Please God may it not become the opposite.