Memoir The Filth issue

The Madrid Orgy

By Daniel Saldaña París

Translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney

To read this story in Spanish, click here.

I lived in Madrid from 2002 to 2006 and studied philosophy there, at the Universidad Complutense. However, I dropped out of college without graduating and returned to Mexico with no desire to rectify my lack of academic qualifications because it would have meant another trip to Spain, something I wanted to avoid at all costs.

My memories of Madrid and the university campus very often seem distorted or unreal, as if in those years my capacity for invention and fabrication had soared to worryingly high levels and it were now impossible to reconstruct the objective truth. To make matters worse, I’ve lost contact with almost all my friends from those days — friends of whom I have rather bitter memories.

But there’s one story I remember better than others, and in a way it sums up my four years of university life. When I returned to Madrid in 2018, the recollection of that story was so vivid that it prevented me from enjoying the city as I would have wished.

When I passed beneath the climbing plants draping Edificio Princesa in the Glorieta de San Bernardo, I recalled that story and, with it, a version of myself I no longer recognized but that still spoke to me, like a phrase whose elusive meaning can never be fully understood.

I lived in that building for three of the four years I spent in Madrid, in an apartment my Spanish grandfather let me use on condition that I didn’t have parties or disturb the neighbors (one of whom, Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Tejero, was famous for his involvement in a failed coup).

In that apartment in Edificio Princesa, betraying my grandfather’s trust in me, I threw a party to celebrate the birthday of my then-girlfriend, C. I suggested we choose a theme and she decided to go with the Wild West. We designed dreadful invitations on the computer, including the word saloon and a sheriff’s badge, summoning “outlaws” and demanding appropriate dress.

One of the few things I’ve kept from those years, one that might help me to grasp the meaning and reach of what happened at that party, is my underlined copy of Georges Bataille’s Erotism.

C. and I used to read Bataille aloud to each other and, for totally unconnected classes, wrote essays about Acéphale — the journal and secret society Bataille headed in the interwar years — or on Pierre Klossowski’s Sade My Neighbor. We also revered a secondhand book about the College of Sociology, a study group that Bataille, Michel Leiris, and Roger Caillois, among others, founded as a cover for the occult gatherings they held in the Bois de Boulogne. But the truth is that at the age of twenty, my theory of dissipation was far in advance of my practice: I was a callow young man from Cuernavaca with a talent for falling in love, and these convictions resulted from the same lack of personality that later led me to poetry and, more recently, Kundalini yoga. “I just want to be loved,” says a poem by Eduardo Milán that I reread from time to time. Any ideology or text that allowed me to belong to a group was brilliant. Bataille and his College of Sociology had been my entry ticket into a group of friends who to me seemed beautiful and sophisticated, and in which C. played a leading role.

My copy of Erotism has lost its original dust jacket, with the detail from Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, and now displays the sky-blue boards of the hardback Tusquets edition, pawed to the point of revulsion by an I who no longer exists. I’m horrified and rather ashamed to discover my notes — in blue ink and yellow highlighter pen — in the margins of the book. Where Bataille writes, “The orgy is not associated with the dignity of religion, extracting from the underlying violence something calm and majestic compatible with profane order; its potency is seen in its ill-omened aspects, bringing frenzy in its wake and a vertiginous loss of consciousness,” (emphasis mine) I’d underlined every single word several times and written, “Yes!” I’d also underlined my marginal note, as though it weren’t already clear that this section was, in my view, important.

For the Wild West birthday party, C. and I made two piñatas. One was dignified and the other ill-omened, with its wake of frenzy and vertigo.

I’m almost certain that at around eleven that Friday night we recited that quotation from Bataille before the first guests began to arrive. To me, used to the less ungodly hours kept in Cuernavaca, the Madrid habit of starting to drink at midnight seemed perfect: it was everything I’d dreamed of in my provincial adolescence.

At first I kept quite strict control over who was allowed in: they were all university friends, disguised as one-eyed priests, burlesque artistes, or sour-faced bartenders. But at some point I became distracted and, when I tried to take an inventory, discovered the presence of a sizable number of law students whom no one had invited and who hadn’t completely respected the dress code.

Strange to say, I don’t remember my costume. In my (surely distorted) memory, I’m wearing a felt hat with absolutely no cowboy connection and I have a toy pistol at my waist, but there may have been some additional elements. By contrast, I remember every detail of what C. had on: a black dress in what looked like lace, a black veil falling over her eyes, and elbow-length gloves.

In her garter belt, which she kept on show by hitching up her dress, she had a real knife — an old faca belonging to her father that glinted against her pale skin.

In a sort of nod to our readings of Bataille, we’d decided it would be a terrific idea to fill one of our two piñatas with raw offal. The other, as was normal, contained candy and fruit.

I’m probably lying about this: it was most likely C. who decided to fill her piñata with offal, and I just went along with it. But I no longer know who I was seventeen years ago. It’s quite likely that I had a less passive role in the whole thing. Whatever the case, we had a traditional piñata filled with candy and another whose papier-mâché shell was damp with blood. We both knew that at some point during the party it would have to be broken. It was a rite of passage, a foundational moment for our secret society. After that party, we’d be prepared to live the dissipated lives, replete with orgies and cheap wine, that we dreamed of when reading French philosophers.

I once wrote a thinly disguised short story based on this same anecdote. But strangely enough, fiction took the edge off the narrative. What in fact happened was much worse and much less credible. In the fictional version, I felt I had to tone things down, and it ended up being a bad story because I feigned an emotional distance from the events that in fact has never existed: even now, seventeen years later, my hand trembles slightly as I write this.

That night, after three or four hours of drinking, I was hammered enough to suggest to C. that it was time to fetch the piñatas from their hiding place.

On the wide balcony of the apartment, we tied a cord to the ring used for the hammock and hung a piñata there. First the normal one, filled with candy. The bulb on the balcony had blown and so we could only count on the dim light from the living room, which did little to illuminate the outer darkness. There were more people than was really safe and I was afraid that when the stick was swung, someone would be hurt, so we dispensed with the blindfolds and simply whacked the piñata with all our might. At the third or fourth attempt, the papier-mâché split and the candy tumbled to the floor. The Spanish guests thought this was great fun and very folkloric, and some of them asked me about the symbolism of the custom. But I was incapable of responding, paralyzed by the anticipation of what was coming a few minutes later.

C.’s piñata, the one containing the raw offal, split much more quickly, at the second swipe. I won’t linger on the details here because this is a story I’ve already told too many times, egged on at other parties by friends who have heard it before, and I no longer have the urge to gloat over it all (quite the reverse: it seems to me a horrible story, one of the saddest moments of my life). The offal fell with a disgusting plop; some pieces were left clinging to the remains of the piñata, and a sadistic friend shook the cord to dislodge them. As it was hard to see anything, the same people who had taken part in the previous splitting of the piñata threw themselves to the floor to collect the candy. When their bloodstained hands touched the revolting, slimy material and the smell of death began to impregnate everything, they sought the beam of light coming from the living room, trying to figure out what was happening. And when they did, they invariably began to scream. One guy, who was six feet tall, told me we were a pair of imbeciles (he was right) and said that what we’d done was both dangerous and aggressive. I started to feel faint. Everything smelled of blood.

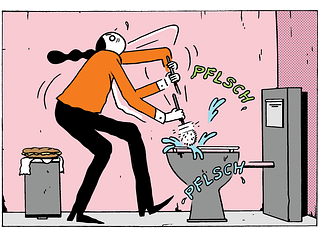

I made an attempt at damage control. The female law students had run crying from the party, followed by twenty or thirty others who didn’t have the stomach for such things. Those who remained were either close friends who had also read too much Bataille or, to be blunt, unhinged individuals who began to toy with the chicken heads still inside the piñata. Despite being drunk, I made an effort to clean up a little. I got a garbage bag and a pair of kitchen gloves and, filled with remorse, crouched down on the balcony tiles to gather up the remains. I vainly entreated the guests not to spread the blood around the apartment and complained that if they weren’t going to help, they should leave me in peace to get on with my task. Only one friend, Constanza, more sober and kindhearted than the others, helped a little. But the blood from the offal had seeped in between the tiles and I couldn’t remove it. I must have been kneeling there in the shadows, feeling the chilly spring wind on my face, for at least an hour.

When I went back inside, the party had moved on to a new stage. The bathroom door was locked and moans could be heard from inside, a couple were kissing with cannibalistic intent in the hallway, and the singles were dancing in a trancelike state, oblivious to the general lasciviousness.

I just wanted it all to end as soon as possible.

I went into the kitchen to dispose of the bag of offal and blood-soaked paper and saw C. fucking some guest I didn’t recognize who was wearing a hat. C. was leaning back against the wall, her dress hitched up, and the knife was lying by her feet on the floor; her lover had his back to me and his pants were pulled down around his knees. To the best of my memory — although I admit that I may be exaggerating, because nothing so disturbing has ever happened to me since — C. looked at me and gave a slight smile, as though the scene were dedicated to me.

Nothing I’d read of Bataille had prepared me for that. I dropped the bag of offal and exited the kitchen on the verge of tears. I’ve been cucked, I remember thinking, all the sophistication of my studies forgotten. I cursed French philosophy and the city of Madrid and wished I were old, suffering from dementia, able to return to a state of Edenic innocence and forget the whole episode. I sat in an armchair in the living room with a glass of wine I’d found on a bookshelf and remained there, stunned, for the rest of the night. The few remaining people departed at about 5 A.M. One or two friends, too drunk to walk, curled up on the floor around me to catch a little sleep. C. and her lover took themselves off to my bedroom, and I guess they slept, too, because I neither saw nor heard any more of them.

A man who was much older than the rest of us, probably around thirty-five, shook me out of my lethargy by unexpectedly asking if I liked Andalusian heavy metal. I said I didn’t, that it was the thing I hated most in this god-awful world, but it made no difference: he took a cassette from the pocket of his leather jacket, put it on, and started to swing his long mane — which hid a receding hairline — as if he were at a gig. Annoyed, I asked who had invited him and he told me he’d spotted a flyer for the party on the floor at the university, and when he read that they wanted “outlaws,” he’d decided to turn up at the party. He didn’t regret it: the bloodied piñata was “cool as hell.” He wasn’t wearing a costume. Without waiting to be asked, he explained that he was wanted in Andalusia for a series of crimes: a few armed robberies. I suggested he leave my home, but it was an unconvincing request, little more than a mumble. He said, “One more song and I’ll clear out, man. Some party! You kids are off your heads.”

At six the sun began to appear over the horizon. I’d been crying and my eyes were swollen. In the early morning light, I was able to see the ruinous state of the apartment and the bloodstains on the floor. The remnants of C.’s papier-mâché piñata, now stained a dark rusty red, made me retch. I couldn’t bear the sight of it all and went out for some air, leaving behind me a veritable carpet of half-naked people and dead animals.

I walked along Avenida San Bernardo, past the Noviciado metro station and Calle del Pez. There were few people around, just the occasional drunk returning home in silence and one or two groups who’d washed up from the nightclubs in Malasaña and were smashing bottles and singing.

On a corner, I saw an illuminated sign for a gay sauna and, on impulse, went in.

In the Bois de Boulogne, during the most turbulent period of his life, Georges Bataille was the head of a secret society that practiced vaguely pagan rituals: there were initiation ceremonies, code words, and, presumably, sexual encounters, possibly even sacrifices. At some point, Bataille came to the conclusion that, following the tenets of his philosophical movement, the society should decapitate him: when all is said and done, the name of the journal that spread their ideas was Acéphale. But the Parisian bourgeoisie who participated in the sect’s activities were shocked by that most eccentric of their leader’s requests and left his head on his shoulders. The society was disbanded and some of those involved distanced themselves from Bataille to take up other intellectual pursuits. Leiris went to Africa and Caillois to Argentina.

On entering the sauna, I was handed a towel and I put my clothes in a locker. I remember that the key was on a rubber wristband. Inside, the clientele was mostly elderly men, but I’m only partially sure of that since for many years, I chose to wipe the whole affair from my mind. An Arab man with a strong accent took my hand and said I should come watch a movie with him. I was grateful for this tender gesture and followed him submissively. The sauna had a small movie theater: three or four rows of seats and a screen showing pretty explicit material. We sat down, and without further ado, he asked me to give him a blowjob.

With scarcely a second thought, I put his dick in my mouth. I was excited, of course — my heart was beating at an incredible rate — but I was also worn out from lack of sleep and everything that had happened during the party, the banquet of offal, C.’s public copulation, and the idea that I’d very likely have to find somewhere else to live since the crypto-fascist neighbors would have me thrown out. It was the first time I’d given a blowjob, and with so much else going on in my head, I was probably making a mess of it. I sucked the Arab man a few minutes more and then, politely apologizing, as if I’d stepped on his foot in the supermarket line, stood up, went back to the lockers, and dressed hurriedly.

Some hirsute men standing in the lobby asked me why I was leaving so soon and I told them I was feeling unwell. They were very kind to me, said I seemed to be in a bad way. Without going into too much detail, I explained that I’d had a terrible night, that my home was a disaster, my girlfriend had left me, and I didn’t know where my life was headed. I stood there chatting with them for a while, and they told me to take it easy. I can’t recall their exact words, but they joked with me, said I was real good-looking, and made me laugh a little. Now, when I remember it with greater clarity than I’ve ever before allowed myself, I think they felt kindly toward me. And today, through the eyes of those two naked men, near the door of a gay sauna, in early-twenty-first-century Madrid, I finally feel kindly toward myself.

Literature has such miracles: one can return to a scene from the past and can suddenly be able to observe it with the eyes of an onlooker, a witness capable of compassion and laughter.

Before leaving the sauna, I said goodbye to those two magical bears as if they were lifelong friends. I thanked them for talking to me and told them they were real good-looking, too. On my way back to the apartment, I stopped at a store to buy detergent.