The Netherlands have long been known for their graphic design and typography, but little attention has been paid to the hundreds of Dutch pulp fiction covers of the early 20th century. The online collections of brothers Hillebrand and Uilke Komrij bring to light the rising globalization of the international book trade through the early 1900s, and, in the decade following the Second World War, the emergence of a popular Dutch design aesthetic.

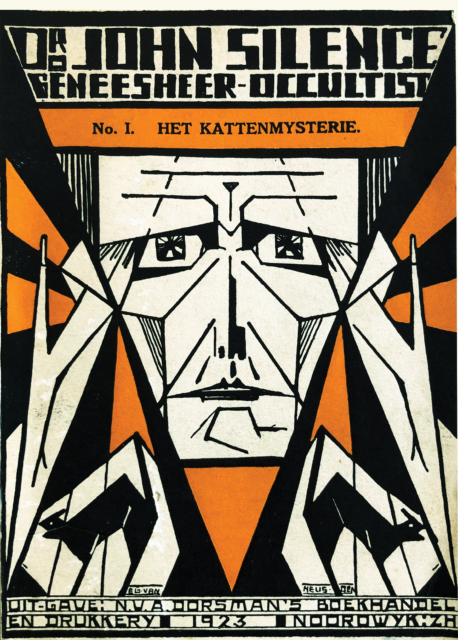

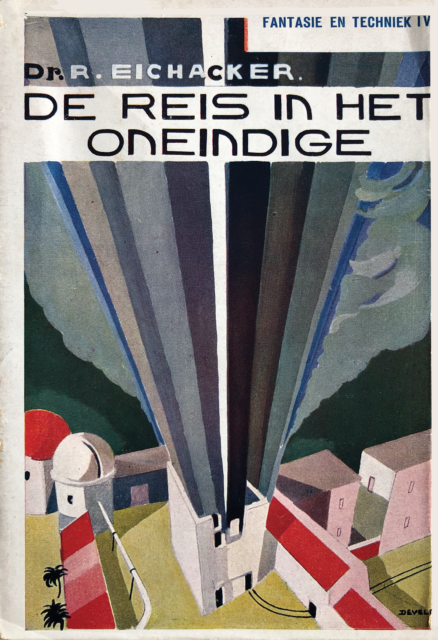

The Netherlands are situated between three different major language centers (France, Germany, and the UK), and over 60 percent of all books printed in the first decades of the 20th century were translations or reprints of foreign literature — much of it popular genre fiction. The Netherlands found itself swept into the global fad of detective fiction, with hundreds of translations of American-style Dime Novels and popular adventure novelists like Edgar Wallace, who, in the 1930s, had more titles translated into Dutch than any other author. The popularity of such detective novels sparked debates about the merits (or lack thereof) of popular fiction, and some publishers attempted to convey the serious literary quality of their work with covers inspired by German expressionism.

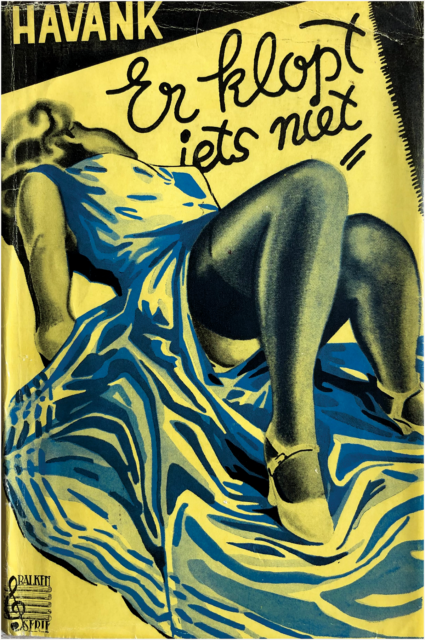

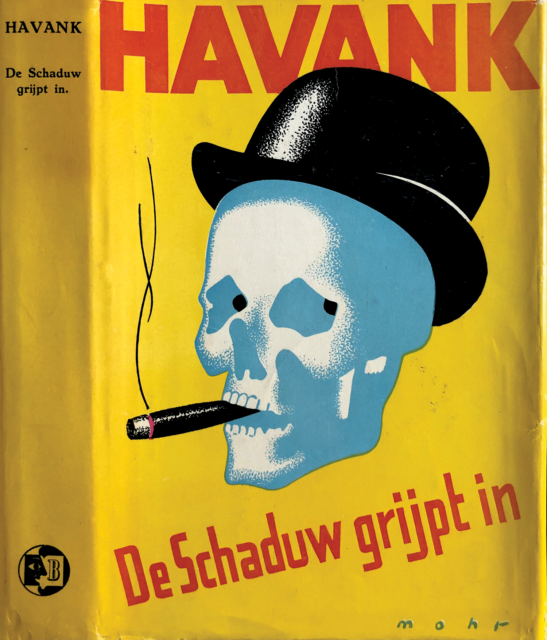

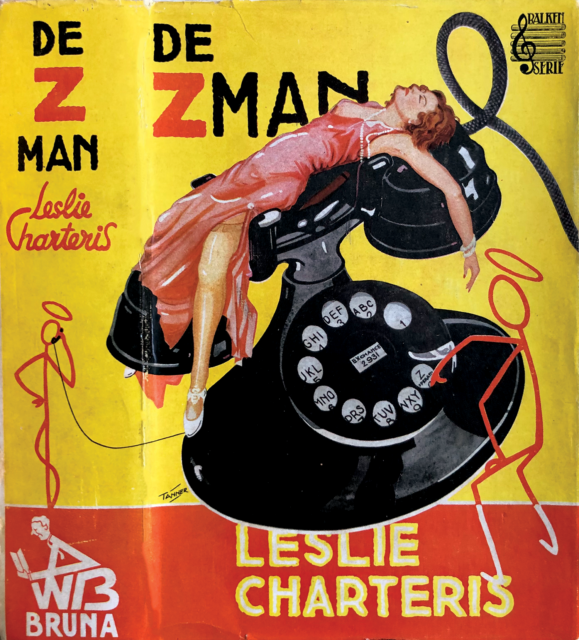

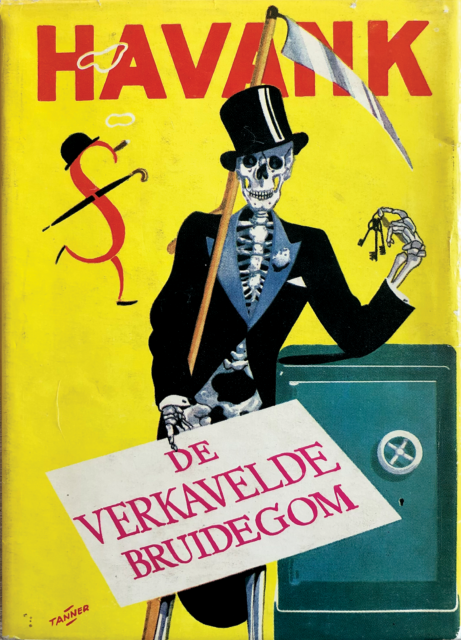

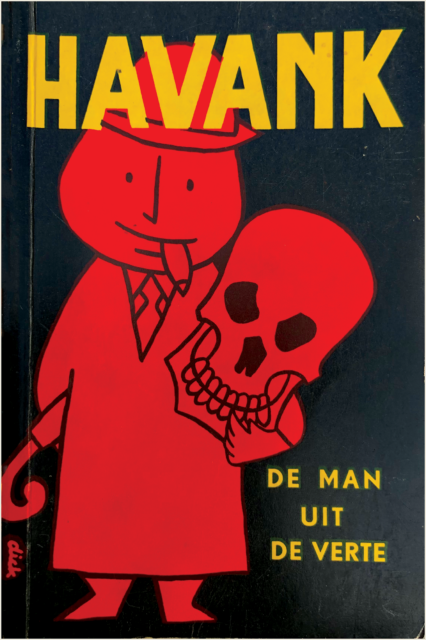

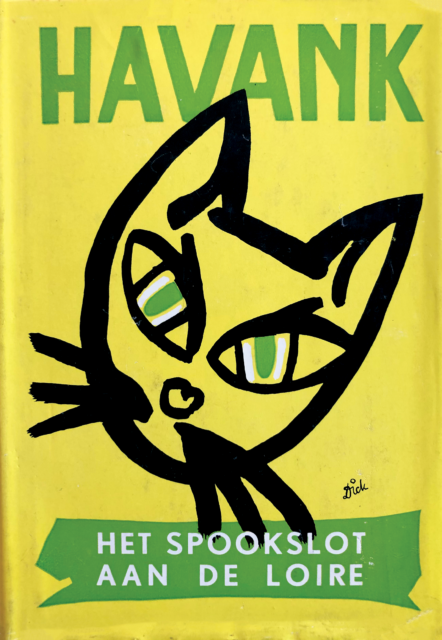

With the German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, the publication of North American authors was banned, but this didn’t dampen the Dutch appetite for detective fiction. A. W. Bruna & Zoon, one of the more respected publishers of detective fiction, pivoted to domestic authors such as Havank and quality cover illustrations, many by “Tanner,” the pseudonym of artist Rein van Looy. The house’s style hearkened directly to the British “Yellow Jacket” series of popular fiction.

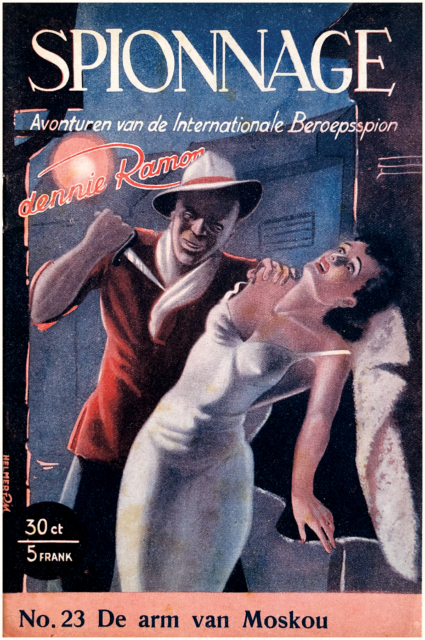

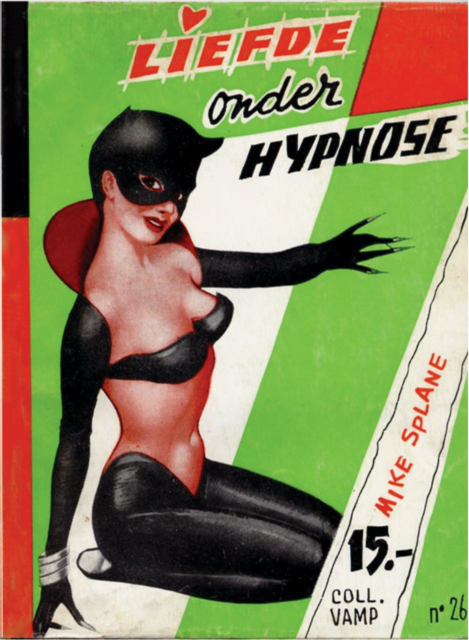

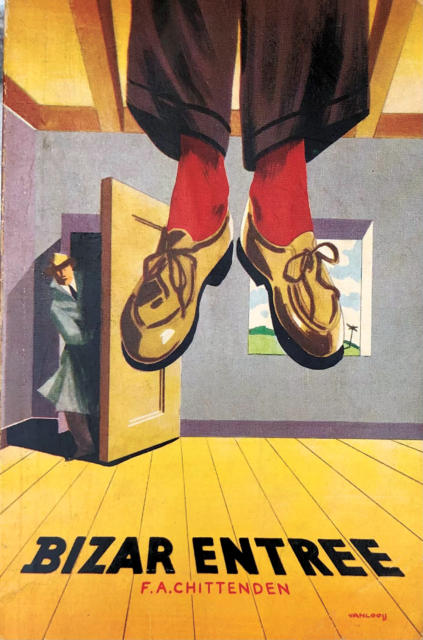

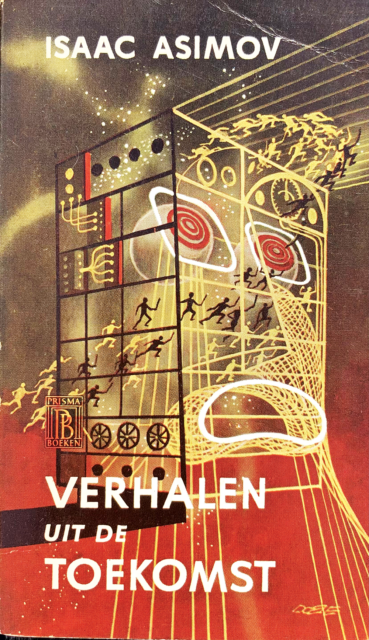

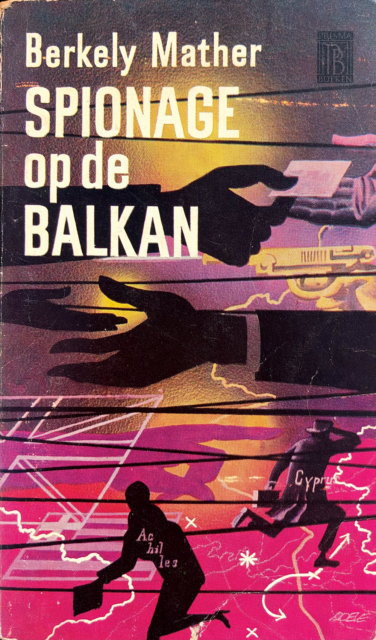

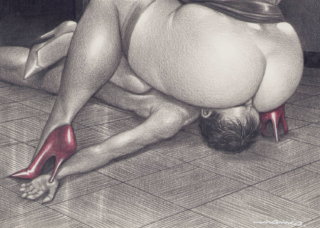

After the war, due in part to the pin-up art favored by American soldiers and in part to the spread of the luridly illustrated American paperback, Dutch design embraced the American pulp aesthetic. Dutch illustrator Helmert R. Miller, who was liberated from a German concentration camp in 1945, cited American pin-up artist George Petty as his inspiration. By the 1950s, Dutch pulp serials, like the Collection Vamp, used covers taken directly from American pulp digests. The pseudonym Mike Splane, author of Liefde Onder Hypnose, was an obvious attempt to cash in on the popularity of best-selling American paperback author Mickey Spillane. The influence of American post-war paperbacks is obvious in van Looij’s cover for Bizar Entrée.

Van Looy’s work paved the way for some of the most famous Dutch illustrators of the 1960s and 1970s. The detective book covers of Eppo Doeve and Dick Bruna (son of the head of W.B. Bruna publishers) established an undeniably Dutch style. Bruna, best known for the Miffy children’s books, perfected his cartoonish, minimalist style for the Havank mystery books, at times directly reworking the Havank covers of the forties and fifties. Doeve’s covers pioneered an exuberant abstract expressionism, hearkening back to the Dutch montage-influenced style of the 1920s. These cover designs from the collection of the brothers Komrij show how genre fiction provided a testing ground for an innovative Dutch style.