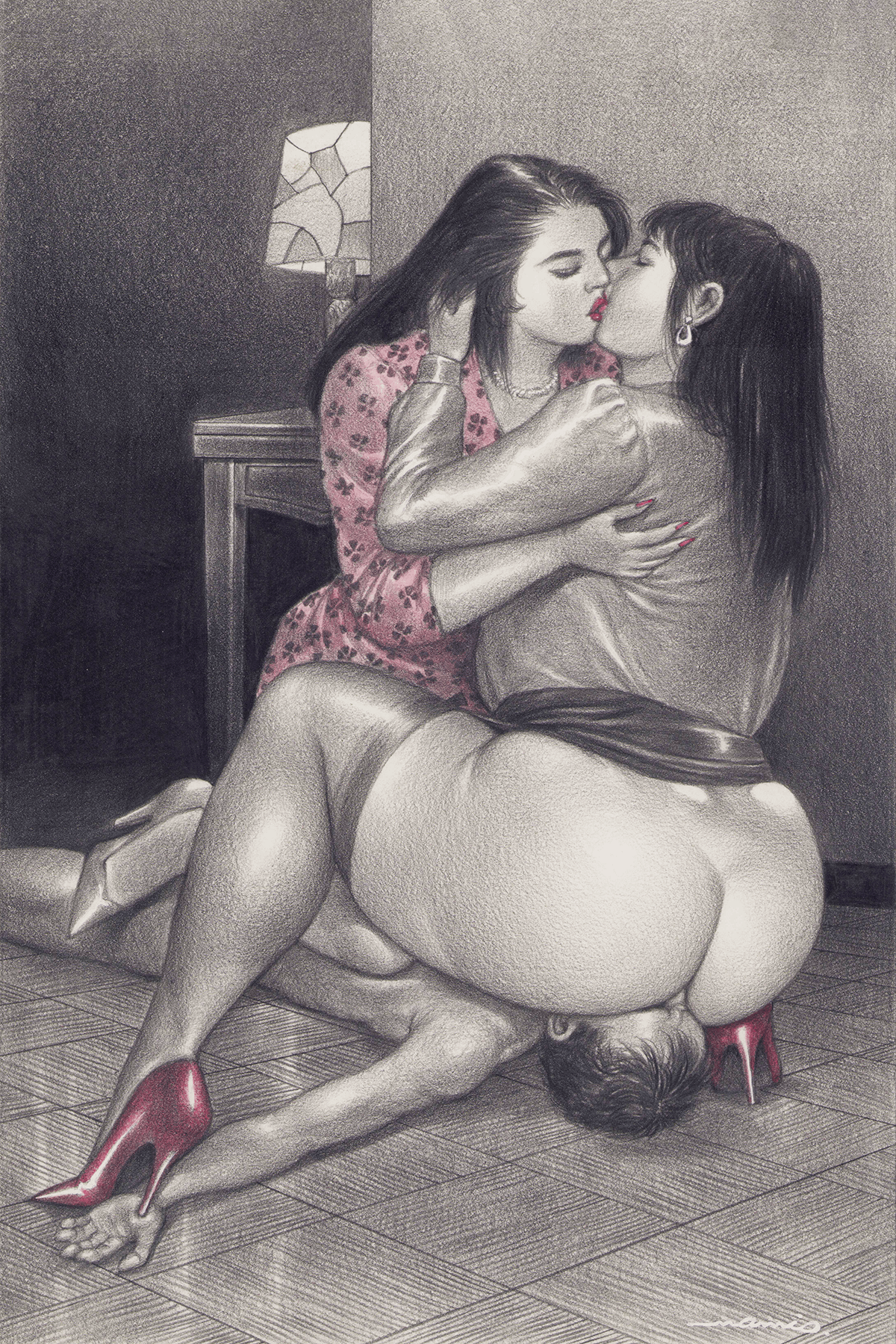

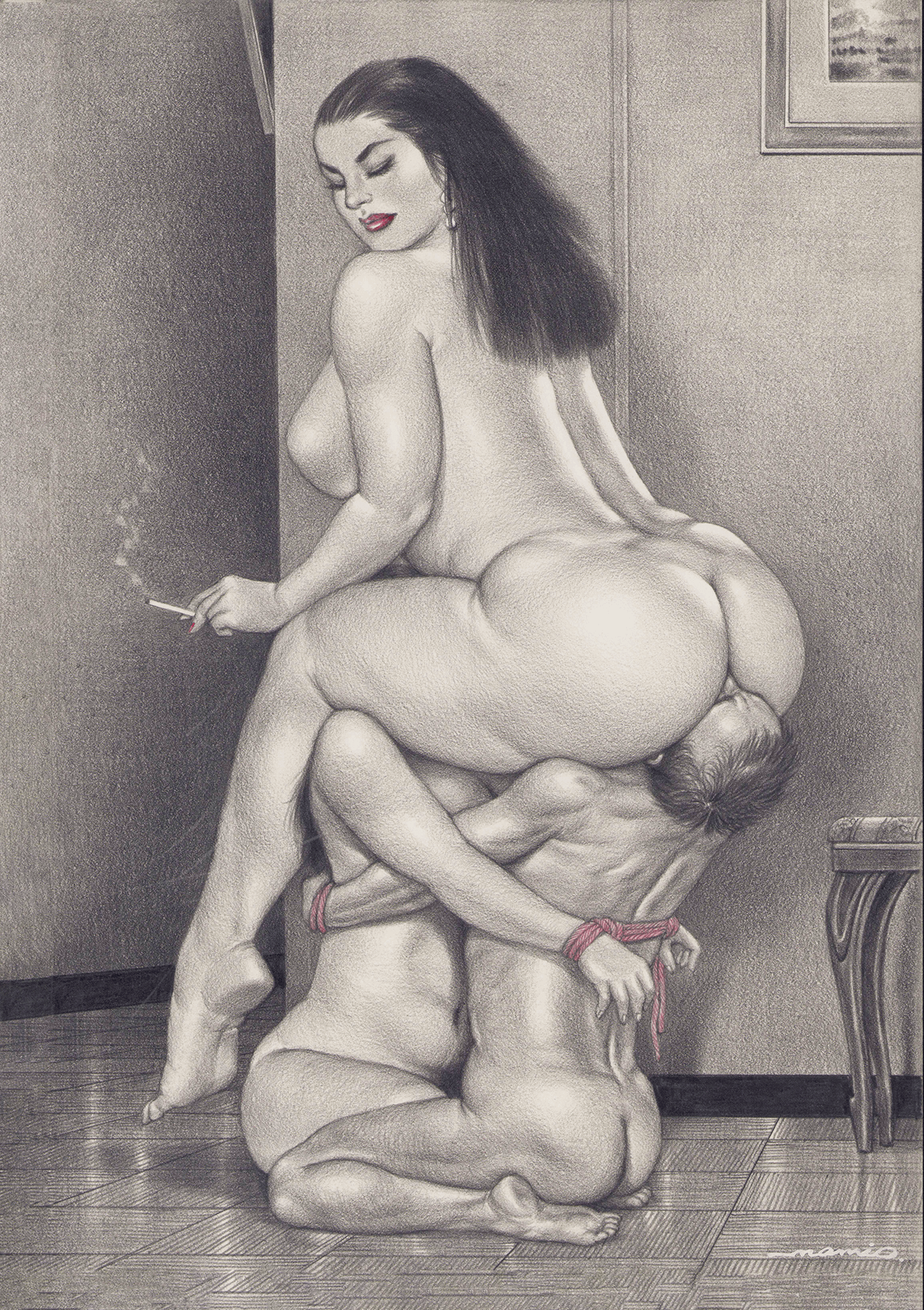

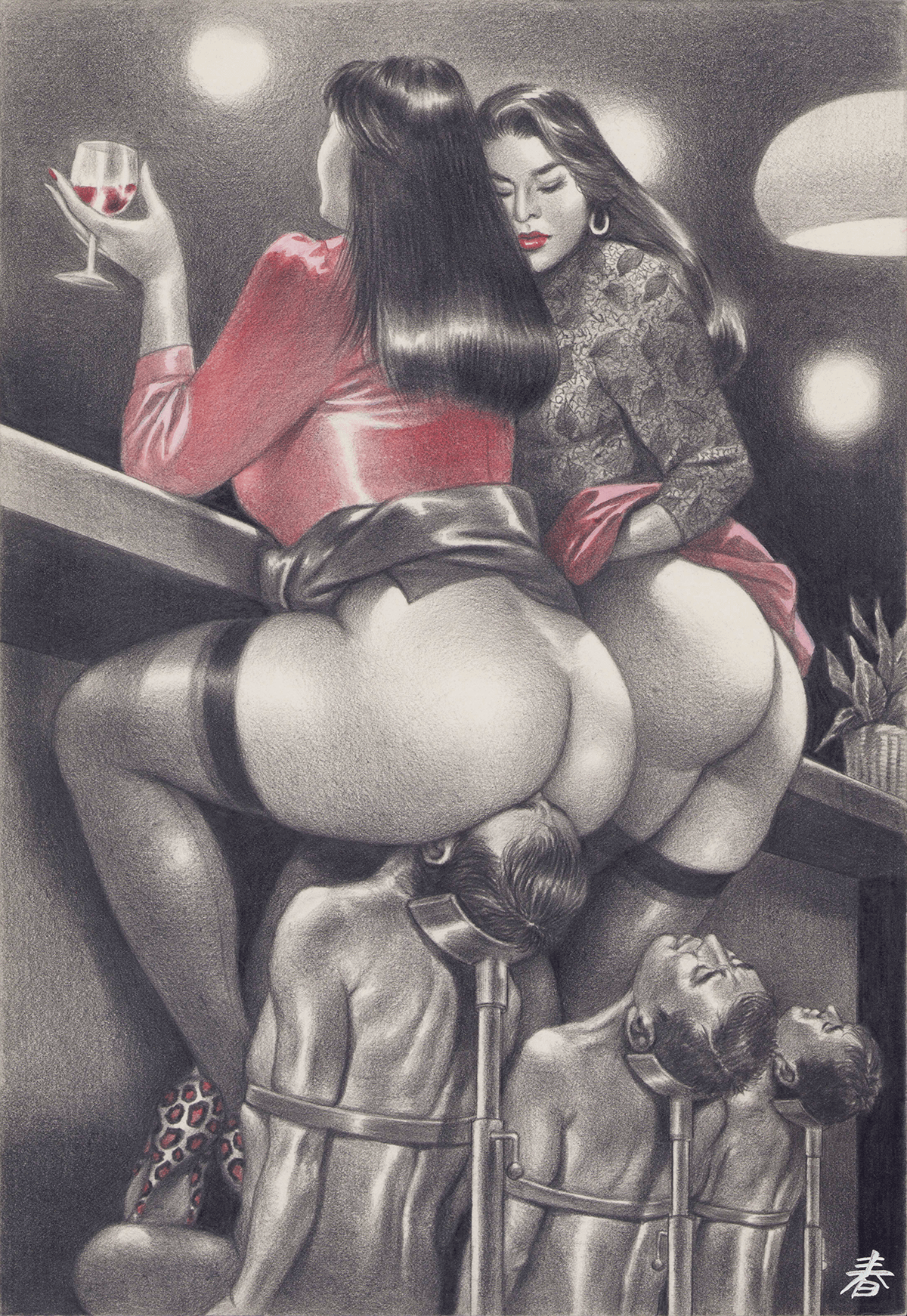

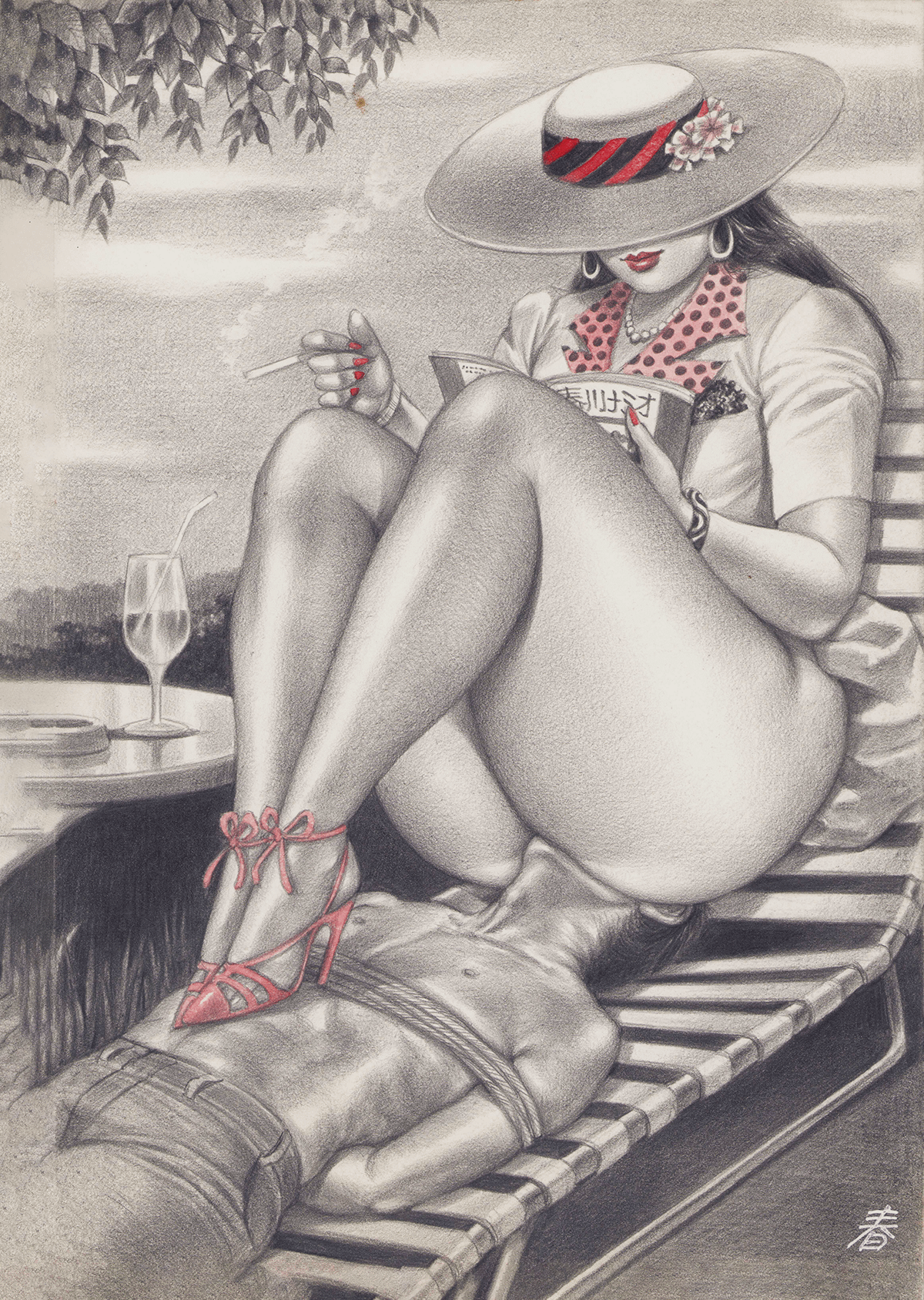

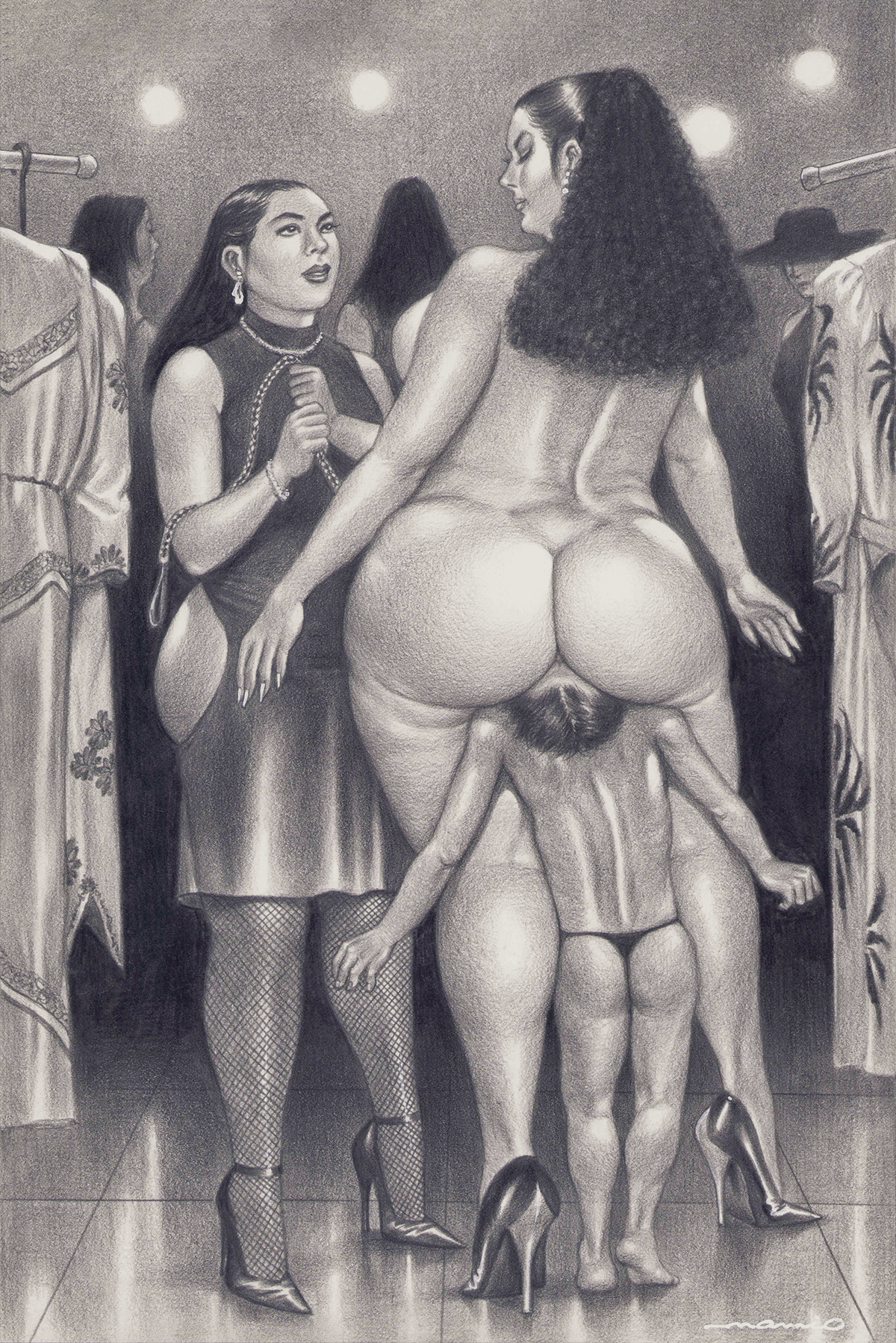

All images by Namio Harukawa, from the monograph “Namio Harukawa” published by Baron Books

He’s an ass and thighs man. They’re ample, sometimes of such girth that there’s a little fold. The women to whom they belong are self-contained. Sometimes the women are just hanging out with others like them-selves. There’s attention to the rest of their bodies, but their asses and thighs are the main attraction. Their power.

What does it feel like to experience desire that is so overwhelming it is suffocating? That’s a key theme of all of these works. They’re all variations on a particular desire, for a sublime geometry of asses and thighs, a suffocating desire. But they’re more than that. They’re also a desire for that desire to be suffocating.

When desires are specific, codified, repetitive: that’s the formal structure of porn. Harukawa is doing something a little extra. These are images about how the desire is experienced. They add a layer. Over and over the men in the images are rendered as puny, weak, reduced, infantilized by their own desires.

You could read the images in a psychoanalytic way, I suppose. That the images are about a certain kind of male desire. That it’s a desire to return to the powerlessness of the infant. Sucking on ass and cunt rather than tit. A desire to return to a moment before separation, before autonomy, before one had to assume the position of masculinity in the world. The images offer a way out of the anxiety of castration: to give in to it. To return to the moment before an awareness of one’s dick, and its supposed symbolic power, even happens.

Psychoanalysis always seems to be more interested in explaining desires away than it is in feeling out their contours and flavors. Particularly sexual desires. It doesn’t really occur to most people to obsess about other kinds of desires. This quiche I’m eating as I write: Why did I get the bacon and cheese one? How does the smell of bacon relate to childhood trauma? It’s not something one usually has to question. Sexuality and gender are special cases. They’re desires that need explaining as we’re all so fucked up about them.

Maybe Harukawa’s desire is about being in the position of the suffocated men. I guess that’s an assumption many would make. But then maybe the desire is to be the women doing the suffocating. If you ask a transsexual, such as myself, this is the sort of thing we might wonder about. A trans reading of any work of art takes away the assumption that the artist’s desires correspond to the gender they apparently present to the world.

If we imagine the desire is to be one of these women, that presents a problem. Actual women don’t usually have as much power as men do in whatever we think is the real world. But this is Harukawa’s world, and he makes the rules. He makes them with great discipline and consistency. Everything is a variation on the power of the ass and thigh. One could just as well read the images as a desire to be a woman, but only in a world where she has this power.

The unreality of Harukawa’s world can make it hard to look at as a woman. The power of women he imagines either doesn’t exist, exists in rare and exceptional circumstances, or is continually trumped by various powers of masculinity. And then some of the images could be read as implying the men are paying customers — with the power to buy this temporary state of powerlessness.

It might be fun, though, to imagine that we, as women, could bear this power without sanction. Nowhere in Harukawa’s world is there any punishment for women who flaunt their power. They don’t have to mask it. Only the women can see and revel in one another here. The men are sightless appendages.

Let’s hazard a little psychoanalysis again: these are also images about scopophilia, the pleasure of looking without being seen. In the logic of the world depicted, men are sightless. Even when we see their faces, they don’t get to see the women. The exception is the viewer, a voyeur on a scene where the “male gaze” is canceled. Where all a man is allowed to sense is the rich smell of cunt and ass.

One could say the images are structured by this male gaze. It’s usually assumed that the male gaze is about power and objectification. It’s actually about anxiety. The male gaze is all about the pull of desire, about how it “unmans” the male viewer. Men have power, but desire has power even over men. And they don’t like it. The male gaze is about managing the anxiety that desire, particularly heterosexual desire, generates in men.

These images solve the anxiety of that gaze in a very particular way. The power of the male viewer is taken away from him in advance. As such, it’s a variation on the stock themes of “fem-dom,” female domination, as a genre of porn in which masculinity is infantilized. Within the work, there’s no separation across which the desiring look can even happen.

But why assume the male gaze at all? One can look at these images as a woman and imagine a world in which we are visible only to one another. It’s hardly Utopia — men still exist. The price to pay as women, to get to live this leisurely life in one another’s company, is to have men’s faces stuffed in our junk. It could be worse. I just wish I had those gorgeous ass and thighs.

McKenzie Wark is a writer from Australia who lives in New York. She is the author of Reverse Cowgirl, Capital Is Dead, and Philosophy for Spiders, among others. Her book Raving will be published by Duke University Press in spring 2023.