The true paradises, Proust wrote, are the ones that we have lost. This demarcates them in space — the rest of the world is no paradise — and also in time: we mourn them, want them back. Eden was never a hope; it was the first departure point.

Derek Jarman was fixated upon that loss. It was why the writer, director, and artist cared so much about gardening. He observed in his journals: “Each park dreams of Paradise: the word itself is Persian for ‘garden.’” In the gardens of the Villa Borghese, near which he spent some childhood years, he remembered that you could find Scipione’s “ostentatious polychrome villa,” which he disdained as “a far cry from Adam’s wooden hut in Paradise.” By his death in 1994, he had made a hut of his own: Prospect Cottage, out on the Dungeness shore, unostentatiously beautiful. It was, he wrote, “the last of a long line of ‘escape houses’ I started building as a child at the end of the garden: grass houses of fragrant mowings that slowly turned brown and sour; sandcastles; a turf hut, hardly big enough to turn round in.” He described the garden of Prospect Cottage as — what else — “paradise.”

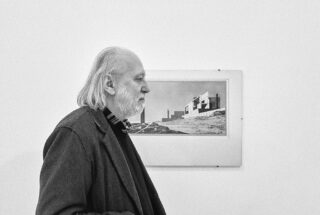

These fantastical sanctuaries — echoes of Eden, the lost ideal — recur through Jarman’s art, from his journals to his films. Tilda Swinton dances at twilight on the enchanted Dungeness stones. The director, pen in hand, gazes out at his patch of earth. Today these images are beloved, and Jarman is akin to an English saint, a queer national treasure for the counter-cultural set. Perhaps it’s because he had the virtue of not being quite like anyone else, one of those distinctive dynamos who seems both unique and, in retrospect, required. Perhaps it’s because he was British, from a land where nostalgia has many flavors but is rarely itself a choice. Given all that, it’s doubly surprising that one of Jarman’s gardens was lost, and that it was made in America. You can retrieve it in his only novella, which was abandoned by its writer back in 1971, but in Jarman’s eightieth-birthday year is appearing at last in print.

Through the Billboard Promised Land Without Ever Stopping is a trip without destination through a surreal and dizzying land. We begin at a “perfectly comfortable villa” in which a young king and his valet live; despite its perfection, they leave it, and set off with wandering steps and slow. Heading down a “Superhighway,” they find oases of neon magic, and a lot of degenerate fun: they stop in Astra Park — “free parking, free love, free souvenirs” — and walk the Lawns of Paradise, a verdant outdoor showroom that hosts “the living rooms of the past.” They then visit the Temple of Autodestruction, where the impresario Borgia Ginz plays host to a wild cabaret in which pigs march across tables, the air is thick with DDT, and a glamorous lady — the “Begum in flowered chintzes” — paddles her breasts in a bowl of soup. There’s chiming, quasi-scriptural anaphora (“And the Pierrot sang… And the air rushes… And John saw…”), but also snatches of queer humor (broken statues with “stone hair permed forever”) and the eroticizing of history (Caesar, Charlemagne, and Richard the Lionheart dancing) — it’s a Jarman film manqué.

“The Billboard Promised Land” was, in the early 1960s, Jarman’s nickname for America, which had stood for abundance ever since he was a boy. In the journals published as Dancing Ledge, he remembered a fifties childhood in which the Land of the Free was “the land of cockaigne… they had fridges and cars, TV, and supermarkets.… The whole daydream was wrapped up in celluloid.” (Cockaigne being a land of luxury in medieval tales; that era being, as Jarman put it in Modern Nature, “the paradise of my imagination.”) It’s tempting to think of Billboard as “cinematic,” too: it hums with detail and color, with the lusciousness of looks. But if this is a dream, it isn’t the American one — or not conventionally. The landscape of Billboard has a Dalí-esque sparseness, a Cockaigne evacuated so that it can be sprinkled with idylls. Some of the wilderness blossoms in visions — mimosas and strawberries, breasts and soup — but when that vanishes, what’s left is a “desolate landscape” with “flaccid undulating hills.” You can see such magnificent vacancy in Jarman’s landscape paintings of the sixties and seventies: vistas in pale block colors, traversed by stick-thin elements. “It was a land,” as Billboard sighs, “to make a traveler despair.” But such is everywhere that isn’t Eden. You have to know absence to feel hope, and then its loss.

Jarman would often start a work with an exit from a perfectly comfortable home. Take his feature-length films: at the opening of The Garden (1990), a voice-over offers “a journey without direction”; in The Last of England (1987), Jarman is seen setting words to paper, and beginning his montage of national ruin. (In the latter, color is downplayed, except in the family movies that portray his own childhood. Elsewhere, he wrote that “in all home movies is a longing for paradise.”) And Jubilee (1978) begins with a royal journey: Elizabeth I and the magus John Dee travel through time to Britain in the seventies, where the pleasures of bingo and disco are stacked against violence on the street. We hear a speech from one Amyl Nitrate (a variant form of “amyl nitrite”, the chemical name for poppers), a punky rebel who paints England as a paradise besmirched by alien men:

It all began with William the Conqueror, who screwed the Anglo-Saxons into the ground, carving the land into Theirs and Ours. They lived in Mansions and ate Beef at fat tables whilst the poor lived in houses minding the cows on a bowl of porridge, whilst they pushed them around with their arrogant foreign accents. There were two languages in the land, and the seeds of war were sown.

Later, clad in a Union Flag minidress, she performs a cabaret “Rule, Britannia!” with dirty dancing and a Nazi walk. Her audience — back for an encore — is Borgia Ginz, who’s now a fusion of media mogul and proto-Thatcherite spiv. He declares:

I build their houses, plan their roads, plant the trees, and run the buses. They’re all working for me. I call it improvement, progress, babe. And they follow blindly. I’m their life insurance. Without progress, life would be unbearable — progress has taken the place of heaven. It’s like pornography, better than the real thing.

When Jubilee was released, the punks didn’t like its insinuations, but Jarman was unrepentant for the rest of his life:

Afterwards, the film turned prophetic. Dr Dee’s vision came true — the streets burned in Brixton and Toxteth, Adam [Ant] was on Top of the Pops and signed up with Margaret Thatcher to sing at the Falklands Ball. They all sign up in one way or another.

Heaven had been abandoned by the kings of the economy and the insurrectionists alike.

Billboard wasn’t the only avenue Jarman tried, and abandoned, in the early seventies. There was also his only poetry book, A Finger in the Fishes Mouth, published in 1972 and mostly forgotten until its reprinting, by Test Centre, only eight years ago. Again, it was an oblivion that Jarman did little to stop; at one point, his partner Keith Collins found an old copy on Jarman’s shelves, upon which its writer quipped: “Don’t read that. It’s puerile rubbish.” In one sense, he wasn’t wrong: largely written on Jarman’s 1964 trip through America, it takes the typical Beat sententiousness and makes it sillier still. And since I’ve been writing about Finger and Billboard, people have asked me whether they’re good, to which the answer is complex: a Jarman neophyte shouldn’t start here, instead of his films or his journals, those lush introspective wells. Yet the puerility of these books, in another way, is turned usefully to their strength: much of Jarman’s puckishness lay in his refusal to mature. Besides, he was in tune with the nation that he was obliquely writing about. Americans have long believed that Eden belongs to them: the seventeenth-century Puritans described their new continent as a paradise gone wild (and there for regaining), while one Mormon tradition still locates the Garden in Missouri, somewhere in the west of the state.

Reading Jarman can feel conspiratorial: everything connects to an unsettling degree. You go looking for words on a certain topic, a particular image or phrase, and there you find them, in the place that had seemed altogether too obvious. To say that Jarman spent his last years chasing bliss, for instance, is to mean it literally: with his body cut off from sensual joy, he caressed states through words instead. In 1993, he wrote his own funeral address, saying: “I die in Bliss, but a shadow in my sunshine day has haunted me all my days.” More involutions, more play with selves. “Sunshine day(s)” is from Shakespeare’s Richard II, a play so exquisite and homoerotic that you’d expect Jarman to have directed it, while “bliss” is from Milton’s Paradise Lost, a filmed version of which, in 1987, he almost did. “Bliss” was also, at that point, the working title for Blue, his cinematic homage to Yves Klein, and “blue,” in turn, would be described in his book Chroma as the color of “the fathomless blue of Bliss,” and as a “terrestrial paradise” — so the constellation grows.

In that chapter from Chroma, Jarman also connected the color blue with the “archaeology of sound.” This was a twenty-year-old memory of one of Billboard’s most bewitching images, from the travelers’ errant journey through the “sacred city of Disc.” In these ruins, “students of literature quietly brush the earth with sable brushes to release the precious fragments of the past.” (“Brush” and “brushes,” like “sunshine day” and “my days,” is a shameless repetition with which Jarman somehow gets away.) This is a place where time can melt. The tenses flirt with eternity, drifting from simple past into present; you might call that present “historic,” though it has the wide-eyed wonder of a script. The drift happens in one other place, on Billboard’s opening page:

The wind stopped; it was perfectly silent.

If you climb the eighty steps to the portico, you will find yourselves in white rooms of perfect proportion and geometry. The clock strikes twelve, a breeze blows the net curtains and a swallow flies in. He circles the room you have just entered three times and flies out again. […] The young King stirs in his sleep, stretches his arms, yawns and is awake.

It is always like this, the young King thought.

Past moves forward into present, and outwards to the conditional mood, then returns to the indicative, and eventually backtracks to the past. The grammar figures the lovely stasis of paradisiacal dreams: they dwell on an Eden we can no longer access, they imagine it anew, then they repeat. Formally, these are closed loops, drawing ceaselessly on a myth whose colors change as time goes by. “What Cockaigne said back to religion,” T.J. Clark once wrote, “was that all visions of escape and perfectibility are haunted by the worldly realities they pretend to transfigure.” They imply, he added, that “every Eden is the Earth intensified, immortality is mortality continuing; every vision of bliss is bodily and appetitive through and through.”

Jarman’s politics were both nostalgic and queer at once: he was conservative despite, and in opposition to, the heady new Thatcherite strain. He knew how ghosts could be fashioned through veneration, and neutered as easily: in a 1986 NME interview, he deplored “the complicity between the avant-garde and the establishment. It’s symbiotic — they need each other.” Above all, he knew that paradise is distinct from utopia: one is forever lost, the other is continually dreamt. Heaven faces a different way. Jarman preferred to look back to Eden, though not exclusively: he thought of calling the film that would become Caravaggio “The Murderer Who Held the Keys to Heaven.” In agony in Dungeness in 1992, he saw himself “neither [on] earth nor heaven,” and he even liked to call flowers “heavenly,” though a garden should be their home. It’s true that since the New Testament, the distinction has been slippery. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus tells the thief nailed beside him that they’ll soon meet in “paradise,” paradeisos, a heavenly reunion. And Jarman was — another of his pleasingly literal joys — a regular for years at Heaven, the London nightclub where, in 1991, he held a party to launch his film version of Edward II. On stage were the Pet Shop Boys, and some footage appears in the video for their single “Was It Worth It?” around the lyrics “all at once / you changed my life / and led me in / to paradise.”

Such a journey is a temptation more than a viable hope, but that’s exactly its allure. It flourishes on the tips of our tongues. Eric Griffiths wrote that heaven, in Dante’s verse, conjured “a continuously enraptured litany of ways of saying, ‘I can’t say’” — a world where that rapture never wanes. Jarman is unlikely to have thought, at any stage, that the Terrestrial Paradise was out there on Earth, but the belief was gorgeous enough: in the medieval era he loved so much, few scholars would have disbelieved it. Their arguments were over its exact location, likely in the Middle East, how it had stayed hidden so long, and how God’s children might find it again. In The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry writes that Eden’s “great isolation” made it a perfect impression of home: afterward, everything became multiple, scattered, a mess in which wrong could proliferate. And think of how gigantic the deserts of Billboard are, or the smooth, slab-like expanses of Jarman’s landscape canvases; or how, amid the derelict docks of The Last of England, figures shrink in the hulking dark. To be out there beyond the sanctuary is to be at risk of solitude.

Jarman was always attuned to loneliness, and as his body failed, his sensitivity grew. He was never short of friends, but he reduced groups to isolates. Modern Nature records him struck by the shopfronts of Hastings, then an ice-cream seller at King’s Cross. In April 1990, he confessed in his journal: “I weep for the garden so lonely in the shingle desert.” AIDS was robbing him of his vision, and darkness encroached upon his shore. I miss one image, in particular, that he came so close to committing to film. As Paradise Lost describes it, there were once stairs between Heaven and Earth: angels glided upon them, and beneath them “a bright Sea flow’d / Of Jasper, or of liquid Pearle.” Then the Fall changed everything. Those stairs were “drawn up to Heav’n,” and Eden was left alone.