In the Same Light: 200 Poems for Our Century From the Migrants & Exiles of the Tang Dynasty

Translations by Wong May

The Song Cave, 362 pp.

Bloom & Other Poems

Xi Chuan

Translated by Lucas Klein

New Directions, 176 pp.

It’s hard to hear around Cathay. As anyone a little bruised by the topic will tell you, Ezra Pound’s slim khaki-colored volume, the product of a hundred international coincidences, collaborations, and misreadings, went off like a bomb in the first year of a European war. It defined how “Chinese” poetry was thought to sound — observational, imagistic, elliptical, heavy on landscape and understated pathos — and used it to explode the maudlin hypotaxes of Georgian verse. The values Pound located in ancient Chinese poetry were metabolized as distinctive traits of English literary modernism, which was then exported globally.

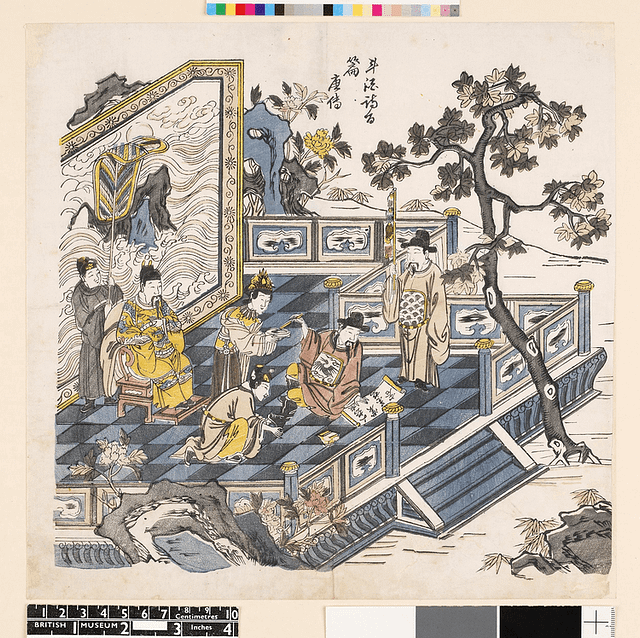

Two recent, exuberant translations of Chinese poetry challenge this stale paradigm from all sides. In the new book, In the Same Light: 200 Poems for Our Century from the Migrants & Exiles of the Tang Dynasty, Wong May (b. 1944), a global writer of Chinese origin, returns to the Tang canon not as to a treasury, but as to a vintage store, rummaging for what fits now and walking out with it. In her radical translations, the gridded five-or seven-character lines of Du Fu, Li Bai, and their fellow bureaucrat-poets, splinter into poignancies jotted down in flight or captivity; her free renderings return motion and breath to these artifacts that have stiffened into sepia and landscape. Furthermore, the thrilling, spidery translations are only half the show: the heart of the book lies in its ninety-seven-page, shape-shifting afterword, where Wong and a magical rhinoceros, who sounds suspiciously like her classical Chinese poetry-writing mother, enter the Tang chat. Wong and the rhino function as impresario-interlocutors, plucking at questions about poetry’s imbrication with Chinese society in the eighth and twentieth centuries, chatting familiarly with Ezra and Emily (Dickinson), and painting in vivid strokes the misery of the An Lushan rebellion (755-763 CE).

Bloom, translator Lucas Klein’s second selection of the prominent contemporary poet Xi Chuan (b. 1963) sings and theorizes what it means to have a body and to write, to love books in a materialist culture, and to be Chinese in a wide range of global and historical contexts. Elliptic lyric seekers need not knock. These are garrulous rhapsodies and charismatic meditations, and they advance implicit arguments against the sight-music of Pound or Bei Dao’s (b. 1949) image-forward “translation style,” which has been widely and warmly received in Western contexts. Xi, whose penname means “West Stream,” writes a maximalist postmodern poetry that raids global intellectual history for fodder. Whereas the Cantos, for instance, encase Chinese content in a frame built from Western epic, Xi’s metastasized fu (賦) — a rhyming narrative form with moralizing tendencies that dates from the Book of Songs (c. 600 BCE) — modernize a catalogic mode with a two-thousand year pedigree, where Heidegger vectors with Luxor, Mencius with Manhattan.

Both books are explicitly concerned with arbitrating a three-way relationship between the contemporary poet, poetry, and history. They resemble each other in positioning the poet as marginal, and poetry as a refuge of value and solace in times of upheaval, including the present. This is the center of Wong’s project: to make suffering, which is always contemporary, palpable again by scraping off the accumulated chinoiserie. There’s a three-step in the afterword that stands in for the whole:

What was it like to be a human being in Tang China?

Twenty-one families together entered Shu, only one man

came back from Camel Pass.

The undocumented with no papers, the refugees with no camp, in the Tang dynasty they have poetry.

The candor is disarming: we notice first Wong’s earnest voice as it asks, then tries to make sense of what it hears, a paraphrase from a line from Du Fu. Beneath the sincerity is a haze of cognitive dissonance. Wong’s question combines attentiveness to historical difference with a frank presentism: she quizzes thirteen hundred year-old objects with the kind of questions we bring to contemporary poetry. The wooly equation of poetry and testimony is implicit, as well as the internal equivalence of the category “human being,” which itself has a decidedly twentieth century fume. But, by framing the passage from Du Fu as a response, Wong dramatizes both what the dead can tell us and what they can’t. The atrocity the poem hints at also reads like a parable for historical inquiry, for translation — for what can be brought back.

Yet the near misses of Wong’s paraphrase are most revealing, as she attempts to reseal the epistemological rupture Du Fu opens. Formally, it’s a sentence any teacher is bound by oath to squiggle: impossible to tell whether the first two terms (“the undocumented…the refugees”) are appositive or serial; the parallel structure they set up isn’t completed; the commas splice; the pronoun “they” is unclear. The content is hardly better: tautologies, then a bromide. And yet the sentence is evocative, and the not-untruth of its litany has a strange, curdling aftertaste.

It shows, I think, what can happen when we turn, earnest and vulnerable, to a poem from the past, how, entering us, it can remake our habits of thinking and feeling: how we put things together. When Wong really listens, Du Fu’s elliptic descriptions, his syntax, and his taste for proverb take over her own writing. Poetry is not the poem; it’s what happens when the reader and the poet meet and change each other. As she declares later,

Poetry lives in the present — though it happened in Tang China.

You are there at the moment of its creation; the poetry comes into being as you read.

In practice, Wong serves an anthology that travels through many of the familiar names and poems found in Three Hundred Tang Poems, the foundational eighteenth-century anthology. The resting stance of the English is a clipped, noun-driven idiom, that, broken sharply across the page, reminds the reader of the fixed forms it dilates. And the more familiar the poem, the more vigorously Wong riffs. Liu Zongyuan is an important poet for the book, held up as “the quintessential poet of exile.” The standard, lilting Walter Brynner translation (1929) of “River Snow” reads in its entirety:

A hundred mountains and no bird,

A thousand paths without a footprint;

A little boat, a bamboo cloak,

An old man fishing in the cold river-snow.

Wong, on the other hand, makes the poem on the page sound and look as starkly alienating as what it describes. Liu’s four tight, five-character lines splinter into clipped, hermetic utterance: “Mountains— // No birds arise”. White space enters between single words, between lines, reflecting Wong’s reading of Liu as a writer of exile and civil strife. A society stripped of its right relations strips the poem of connective grammar. The poem breaks off:

Man

Seen

Casting

Cold river snow

Any motion that happens in this version is only a trick of the reader’s eye, as the typography forces saccades that flit, ghostly, over the single words strewn on the snow of the page like footprints. This is high Modernist technique (an American reader might hear Moore, or Williams) returning ouroboric to its primal scene. Notwithstanding its sly charm, the ambition of In the Same Light — which, even in its title, pitches the language of the present into the past, and vice versa — is as immense as those Modernist predecessors. This raid on a classical tradition ranks her alongside remix scholars such as Alice Oswald, Anne Carson, Christopher Logue, and Eliot Weinberger; the refusal to treat translation as less expressive than original verse calls to mind recent weavings such as Hai-Dang Phan’s Reenactments and David Ferry’s Bewilderment.

If Wong emerges sly and slow from her materials, Xi Chuan struts forward in Bloom’s first pages. The long title poem, which opens the book, is a series of imperatives: the reader is instructed to “…bloom to my rhythm / close your eyes for one second breathe for two be silent for three then bloom.” Lucas Klein’s propulsive translation gets at the poem’s focus on breath, rhythm, mantra as ways of capturing the reader in the poem; this flirtation and its strategies are the real subject of the poem. It’s a good gateway. The reader’s very body becomes part of the poem: we’re hooked in. And, despite the eros along the way, the endpoint of the poem is interpersonal power. It reflects the crisis of modern poetry’s authority in contemporary China, which is more pronounced because of the greater cultural esteem of Classical poetry. If we acquiesce to Xi’s bardic charm, it’s hard not to also hear in such devices a reflection of how a different kind of authority is created and maintained in contemporary China: “so I order you to bloom that is request you to bloom/ I humbly implore you”. For Xi, the world of poetry is no egalitarian refuge from actual political control, but its translation, a shadow country made interesting, and sometimes erotic, by the play of hierarchies.

It might be useful to note that Xi, like many internationally prominent Chinese poets, began in the eighties as one of the “Obscure poets” or “Misty Poets,” (so called for their highly coded reflections on the Cultural Revolution). A later style, dubbed “Intellectual,” followed in the nineties, as the country’s focus shifted to economic development, and modern poetry was (further) marginalized. In this collection, after the direct bravura of “Bloom,” it’s hard not to hear in the mostly long, mostly charismatic monologues a retrograde grandeur, a kind of main-character syndrome à la Richard II: “Shakespeare wasn’t left-handed, but he never dreamed of becoming Shakespeare / How could Shakespeare dare steal a professor’s job, especially a professor in China?”

Michelle Yeh has argued that the cult of the (tragic) poet has a special religious resonance in contemporary China; the poet sacrifices himself to obscurity in the name of all those values left behind by the broader, materialist society. Enter Xi, likening himself first to Shakespeare, then other world poets. In a prose poem about walking around Manhattan as he thinks about the cultural construct of New York, Xi writes, “One day, Ezra Pound will stroll through the streets of Beijing and sigh, ‘There is nothing in Beijing that can be called Beijing.’ And you’ll say, ‘Keep looking,’ and see if he can discover any secrets.” Xi sets up a slow-motion chiasmus, in which China and the West take turns encountering and correcting each other’s fantasies of cultural and linguistic hegemony (“that can be called Beijing”), in the person of their respective grandiloquent poets. Compare Wong, who imagines poetry being as valued today as it was in Tang China: “John Ashbery in Kabul holding peace talks with the Taliban? Louise Glück as Secretary of State? Interesting. Would that change the world?”

Xi’s poems often land in prose, either entirely, as in “Random Manhattan Thoughts,” above, or tactically, as in the ambitious performance “Abstruse Thoughts at the Panjiayuan Antiques Market.” The diminutive titles are belied by the scale and erudition of these meditations, which make refreshingly earnest claims for the power of thought, and genteel culture, to reorder and pronounce judgment on the chaotic welter of commodity culture. In Xi’s hands, the fu becomes the right mode to think through the hucksters, trinkets, buyers, and fantasies that fill the massive bazaar that the title refers to:

Fake antiques are also the fruits of labor, whose cost can never be eradicated, but to pass fake antiques on to people is immoral.

Most real antiques come about through grave robbing, but that’s immoral, too.

The entire Panjiayuan is an immoral place. Why is it so enchanting?

…

This is a place for the acquisition of knowledge, correct knowledge and incorrect knowledge.

…

This is a place where city and country, home and abroad, modernity and antiquity, thepresent and the present all come together.

So it isn’t the present, it isn’t antiquity, it isn’t abroad, it isn’t the country, it isn’t the city.

Thought, we like to think, aims at clarity, at resolving contradiction. Here, however, contradictions are the point; incorrect knowledge, a paradox, remains knowledge. Likewise, the syllogism of the first two and a half lines attains a conclusion (“…is an immoral place”) that utterly fails to explain the individual’s experience of “enchantment.” Meanwhile, reminiscent of the authority play in “Bloom,” the half-ironies of Xi’s schoolroom manner, flagged by the italics, flicker and crumple. This is poetry inserting itself in the place of logic: poetry that drugs logic, steals its clothes, and presents itself as the sole principle that can make sense of chaos. Though logic says a thing can be either a or b, poetry knows it must be both; like improv comedy, it says yes-and, and remains open to what comes next. Like improv, too, it’s a mode whose shifting perspectives deflate pretension, and Xi’s speaker, dwelling with real sympathy on the sham and hypocrisy in the Panjiayuan market, comes to see himself, wryly, from a distance: “Trafficking in fakes he trafficked himself fake. / Trafficking in goods of the dead he trafficked till he died.”

The third paragraph quoted above, “This is a place…,” is a good place to end. It’s a deictic construction, meaning that “this is”, and the “it isn’t” in the next line depend on context, or indexing, for meaning. They refer equally and ambiguously to both the physical Panjiayuan and its shadow, the place the poem creates, that we inhabit as readers. As in Apollinaire’s Zone, or in Wong’s ventriloquy, the poem/Panjiayuan becomes a twilight sort of no-place, all borders, that negates our most fundamental cognitive principles. By its end our ways of evaluating the world — true, false; now, then — have been eroded. Yet the pleasure of inhabiting this freedom from firm knowing, and the persistent linguistic frisson it occasions, compels us to keep following Xi’s speaker into the deep past or the future — it’s impossible to say. His last word, like that of a Tang exile, reaches us from the border of knowledge:

While the wilderness of occasional human and animal bones, and the mountains

of booming silence become solitude itself.