After the end of my marriage, I began assembling a “Daydream Dossier,” gathering texts and art that captured the invention, whimsy, and desperate desires of daydreams: Frida Kahlo’s paintings of beating hearts, cracked landscapes, and floating umbilical cords; Kiki Petrosino’s lyric daydreams about Robert Redford (“It’s smoked salt from Wales, Redford says”); Wangechi Mutu’s fantastical creatures roaming painted landscapes; Marc Chagall’s couples in flight. I’d always been a daydreamer, but in the aftermath of my marriage I started to feel an intensified version of the shame I’d often felt about my daydreams. Had my daydreams at the end of that marriage been lanterns illuminating alternate futures, or simply escapist fantasies?

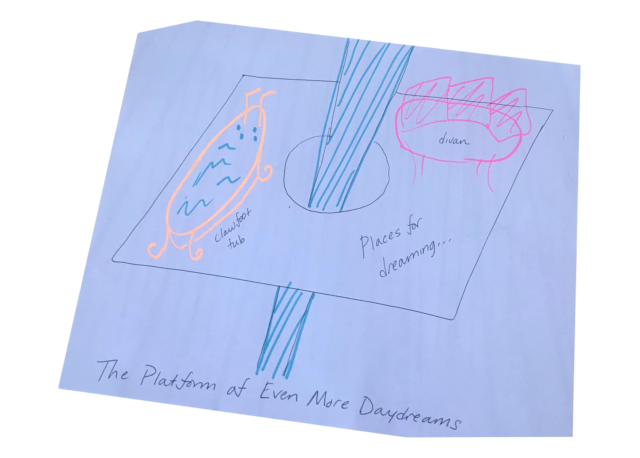

I’ve always believed in writing toward shame, following it like a smoke signal — the way you might spot curls of steam rising from the ground and know they indicated subterranean heat. Sources worth digging into. So I started daydreaming (ha!) about writing about daydreams. I wondered: Did other people daydream like I did? How did people daydream differently? I started asking people about it. I started asking everyone about it. Their responses became part of my Daydream Dossier as well. I researched the ways psychologists had studied daydreams, from Jerome Singer’s “Imaginal Process Inventory” to Eli Somer’s International Consortium for the Study of Maladaptive Daydreaming. During an art session with a beloved tween, we each drew architectural plans for fantasy treehouses. Mine was called the “Treehouse of Daydreams,” and included a clawfoot tub (for disappearing), broken clocks (for forgetting), and a buffet of endless desserts (for indulging).

As my Daydream Dossier grew, I could feel myself approaching the top-heavy black hole of Too Much Research — too many ideas and no idea what to do with them. The territory felt infinite, impossible to put my arms around, like the endless map I’d encountered in a Borges story: a map of the world that eventually grew as large as the world itself.

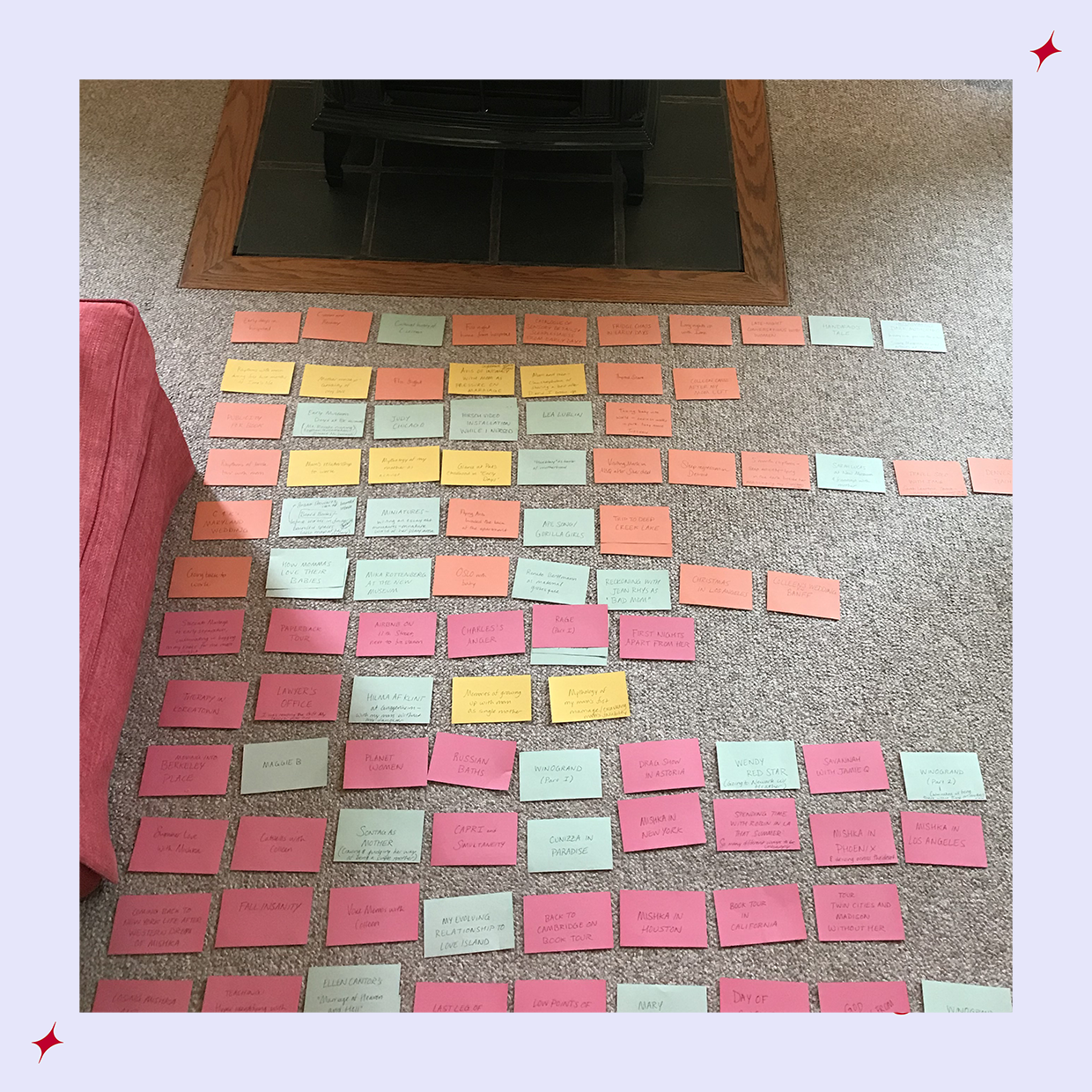

I knew what I needed: index cards. And some floor space.

As part of our divorce settlement, my ex and I had agreed that he would have our daughter for Thanksgiving, and as I approached the first Thanksgiving I’d spend without her, I felt a deep, panicky sense of anticipatory loneliness. The holiday loomed like another kind of black hole. But there was no avoiding it, only passing through it. So I decided to rent a little cabin in the middle of Delaware, and spend the weekend wrestling with my Daydream Dossier.

Oddly enough, I’d always daydreamed about Delaware — a question mark in the middle of the Eastern Seaboard; a place I’d glimpsed from train windows, but never actually seen. My cabin looked like a witch’s cottage, with tangled ivy and slanted gables, a second-floor living room with a potbellied stove and (if you pushed a couch out of the way) some carpeted floor space. Also, an instant kettle I could use to make Cup-a-Soup. This was all I needed. I could get to work. First, I unwrapped my pack of multicolored index cards and began writing down all the bits and pieces of what I wanted to say about daydreaming: daydreams of my own (pink); the daily life from which this daydreaming had emerged (orange); art about daydreams (green); conversations about daydreams (yellow).

Laid out across the carpet on the second floor of my witch’s cabin (my own treehouse of daydreams), these index cards began to convince me that this infinite map could actually become an essay. Laid out as index cards, the ideas became something I could touch, something I could see, and something I could rearrange. Their delightful physicality helped me understand one of the craft imperatives of the project itself: if I was going to write about daydreams, which were intrinsically, helplessly abstract, I needed to ground the writing in the physical, daily world — all the proximate, ordinary circumstances that daydreams emerge from.

Using that weekend to make an outline of my daydreams was a way of taking something painful and asking it to bear fruit: multicolored, papery, rectangular fruit, each one measuring three by five inches. This felt just right, as daydreams themselves are often fruits growing from the rough terrain of boredom, illness, loneliness. For a long time, the working title of the essay was a quote that the artist Jenny Holzer printed on posters and billboards all over New York City in the early eighties, a quote that I taped to the wall of my witch’s cottage: IN A DREAM YOU SAW A WAY TO SURVIVE AND YOU WERE FULL OF JOY.

Read Leslie Jamison’s essay “Dreamers in Broad Daylight: Ten Conversations” in the Ecstasy issue. She would also love to hear about your own daydreams.