I was raised in a family of women. I had two sisters. My grandmother and my aunt spent a lot of time in our home. We were all outspoken; we all had big personalities. And at the center of it all, there was my father. My father was not a feminist. Sometimes he would say things in front of me that were misogynistic, or at least stereotyped. But I found some papers he wrote when he was quite young, and every time he talked about Morocco and the transformations the country had to go through in order to develop and achieve a better quality of life, he always mentioned the place of women. He was aware that he lived in an unjust, patriarchal society but that was not enough to make him a feminist. On a daily basis, in our family life, he was the perfect incarnation of the paterfamilias. My father only ever went into the kitchen to ask for something to eat or drink. He never did the grocery shopping, and he hated the idea that someone might see him in the supermarket. He never changed a diaper, never gave us baths. When we went to school in the mornings or went out in the evenings, he would inspect our outfits and send us back to change if he thought our skirts or shorts were too revealing. I don’t think he ever felt guilty about sitting on the terrace reading while my mother exhausted herself doing the shopping, the cooking, and the housework, all in addition to her job. He often made jokes about the fact that he had no son and how sad that made him. This was, unquestionably, one side of my father — a side that my sisters, my mother and I battled constantly, with whatever weapons we possessed.

And yet, over time, through living with us, through hearing our protests and arguments, my father changed. After all, he was the father of three girls, and he understood that we would suffer injustices. For instance, he rebelled against the Moroccan inheritance law which states that a girl inherits only half of what may go to a man. Through knowing us, my father found himself faced with real, living individuals, and while his prejudices and stereotypes were not simply swept away, they did come to seem insufficient. He always told us how important it was, particularly for a woman, to get an education, to work, never to be dependent on a man. He was always very harsh with men who were vulgar or violent toward women. He was disgusted by such behavior and was not afraid to make that clear.

During his life, my father suffered a fair share of loss. When I was thirteen, he lost his job. Involved in a political-financial scandal and later imprisoned, he lost his friends, his social recognition, and his role as the alpha male. My mother was now the one working and providing for the family. I know that this was a tragedy for my father, but I also saw my father free himself during those long years of isolation. He accepted the loss and rather than grieving, he began to look at the world differently. He looked differently at his wife, who worked with courage and dignity and to whom he owed so much, and at his daughters, who did everything they could to do well in school and make him proud. The world in which he had been raised, which glorified male rivalry and the thirst for domination, appeared to him, at the end of his life, as absurd and destructive. Perhaps this is also what it means to be a good man? To accept loss and to offer oneself the possibility to change in relation to the women in your life. To listen to them, to look at them, to become aware of their individuality and their right to privacy.

Despite all this, at my father’s funeral I was told that women could not accompany the body to the cemetery. My father’s corpse was laid on the floor of the white-draped living room. He was wrapped in a shroud while the men around him intoned verses from the Quran. My mother, my grandmother, my sisters, and I sat on a couch and wept. Then an ambulance arrived, and my father’s body was taken outside. The men buttoned up their suit jackets and walked toward the front door. I followed them and I still remember, with heartbreaking precision, the sunlight on the avenue, the ambulance with green writing on its sides, the men getting into their cars, and me, standing there in my borrowed white djellaba. Standing there and wanting to scream at the injustice. I went back into the house. The other women explained to me that we had to wait and prepare the meal, which had to be something simple, because it was forbidden to cook in the house of a dead person.

I tried, but didn’t always succeed, to raise my son outside of gender constraints. I tried to open his eyes to the injustices of the world, particularly to the injustices that women face. But I have never attempted to be a perfect mother or to over-sacralize my role as a mother. My son’s father cooks, cleans, comforts him in his sorrows and goes to meetings with the schoolteacher. This example of fatherhood is much stronger than any speeches I might make.

Often, my son surprises me. One day, while we were on vacation, he ran out of clean clothes and borrowed a pink floral outfit from his cousin. When I told him that the other kids might make fun of him, he said, “So what? It’s not an insult to be a girl.” On another occasion, while I was talking about feminism with my sisters, he suddenly grew angry. He said, “I’m sick of your feminism. That’s all you ever talk about. And the men, you think they don’t suffer? It’s hard to be a man too.” Of course, he was right. That day, I thought about all the pressure put on little boys: The way they are told not to “cry like a girl”; the images of strength and violence they are confronted with from an early age; the rigid standards of masculinity they are asked to conform to, often forcing them to hide their emotions. I remembered when I was summoned by my son’s teacher after he fight he’d had with a classmate in the schoolyard. I arrived horrified and confused at his behavior, but the teacher reassured me: “It’s normal,” she said, “He’s a boy.” This same teacher considered it normal that boys do not like to read, that they are lazier and less diligent than girls. She expected almost nothing from the boys she taught.

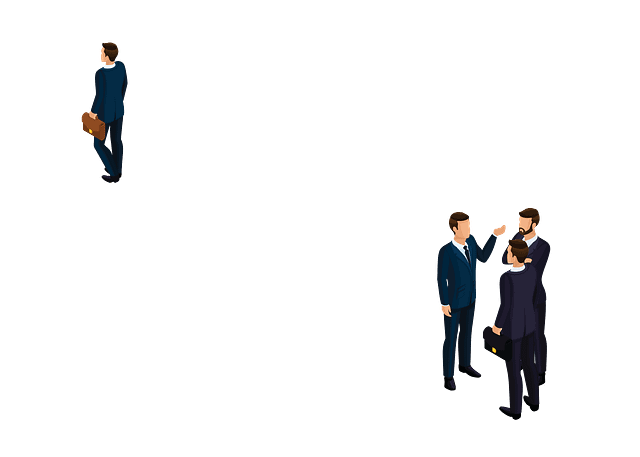

How is it that, for centuries, all the nice men, the good fathers, have not put all their energy into combating the patriarchy? We don’t need the nice men to just be nice, we want personal revolution. And of course, this is where it gets awkward. Most men can acknowledge equality as a good idea in theory, but ultimately they refuse to give up anything important: their seat in parliament, their place on the board of directors, their free time. What of the nice men who still make vile jokes about women, have never cooked a meal, pay their female employees less than their male counterparts? How many times, in Morocco, have I met educated, open-minded men who, when their parents die, demand a greater share of the inheritance than their sisters? How often have I seen a man congratulated for washing the dishes? When my husband gave up work to look after our children so I could travel, people reacted as if I’d married a saint or a superhero (while a female friend of mine who chose to become a housewife is regularly treated with contempt).

What men need to do is question themselves — every day, in every aspect of their existence — about how they can help women to lead free and fulfilling lives. This self-questioning must take place at home, as well as at work or in public places. Men have to make the effort — and this is not easy — to question every aspect of their behavior. What they might perceive as natural — waiting for their wife to make dinner or clean the toilet, going out with friends while their wife takes the children to their swim meet, letting their wife do all the planning and worrying for the household because “she’s more organized” — has to be reconsidered. For the world to change, men must give up their many privileges. Really give them up, in a concrete and active sense. What they must do is to contemplate a whole new way of being a man. Men benefit from the patriarchy. But as my son has taught me, they can also benefit from feminism.

There is one word that I have not yet written. A word that seems absolutely central to me. Love. Because if I have spent so much time seeking the company of men, observing them, studying them, following them, it is also because I loved them. Or, at least, the possibility of love for them lived inside me. What do we do with love? What do we do with desire?

When I was a teenager, most of my friends were boys. Perhaps this is unsurprising in some ways. I wanted to be free; boys were free; ergo, I wanted to be a boy. I was always, even as a little girl, extremely curious about boys. The world of men was, to me, uncharted territory. I vividly remember an embarrassing episode from elementary school. There was a medical check-up and the boys and girls had been separated, each gender in a different classroom. We were standing there in panties and undershirts, terrified of that potbellied doctor who had an enormous wart just above his lip with tufts of hair growing from it. I don’t know how I managed this, but I ran out of the girls’ room and walked barefoot and half-naked through the playground before squatting outside the door to the boys’ room, where the teacher found me trying to look under the door. I didn’t see anything, at least nothing that left the faintest trace in my memory, but I do clearly recall the desire I felt, that eagerness to know boys.

The paradox is that in sexually segregated societies, where desire is suppressed and relations between girls and boys are under constant surveillance, girls are even more attracted to boys. For me, they were forbidden fruit, so I was desperate to taste them. From a very young age, I adored men. I glorified them. For me, they embodied freedom while so many women seemed submissive, insipid, superficial, hypocritical. I didn’t want men to possess me, I wanted to be like them, to be them. I perceived the world as being divided into the dominant and the dominated and I wanted to be on the right side of that line. I wanted to sully myself and, in doing so, to be excommunicated from the virtuous world of women. I hung out with bad boys. I wanted to fight. In the movies I watched, in the books I read, I always identified with the male characters, whom I admired for their courage, their boldness, their strength. As James Baldwin would say, I was an Indian who was rooting for the cowboys.

It was around age thirteen that I learned exactly how boys had more freedom than girls. Their parents were less reluctant to let them go out. They went surfing at the beach or to the movie theater. Girls had to jump through more hoops to be allowed such pleasures. It was during this period that I met a gang of boys who are still like brothers to me today. I wanted to rid myself of femininity. I’d had enough of dresses and dolls and conversations about girl stuff. Though I couldn’t have fully explained this at the time, I sensed that being around boys would toughen me up. By entering their world, I could solve a mystery: what they said about us, how they saw us, what we meant to them. My conclusions were, at first, not especially heartening. Those masculine friendships tended toward vulgarity, boasting, and a sort of violence. They talked about girls in crude and often insulting terms. What they wanted to know was who did it and who didn’t. The ones who didn’t do it were considered uninteresting and the ones who did it were whores. For boys in Morocco, prostitutes occupied an important place in the discovery of sexuality. I knew that several of the boys I hung out with had paid for sex. They talked about it with a casualness that shocked. They gave the impression not only that they felt no compassion for those women, but even that they actively despised them.

Did I hate those boys? Did I try to convert them to feminism? No, I don’t think I did. To be perfectly honest, at the time I was proud to be the only girl in the gang. That pride seems idiotic when I think about it now. But I accepted it. I even laughed at their dubious jokes, sometimes I made such jokes myself. My terror of being dominated, reduced to the image that they had of women, led me to betray myself. Living with those boys, behaving in such a cowardly way, like a sell-out, I also came to understand how mob mentality works. There is an omerta, a code of silence, in groups of men, an instinctive urge to protect one another. Even the “nice” men, when they witness degrading or criminal behavior, tend not to speak out.

Simone de Beauvoir’s famous formula — “one is not born a woman, one becomes one” — is also true for men. This is what I wish for my son: that he can invent his own way of being. I would like him never to feel obliged to laugh at dirty jokes, to puff out his chest. I would like him to erase, on the ground, “those chalk marks,” as Virginia Woolf calls them, that constitute the invisible but cruel border between women and men.