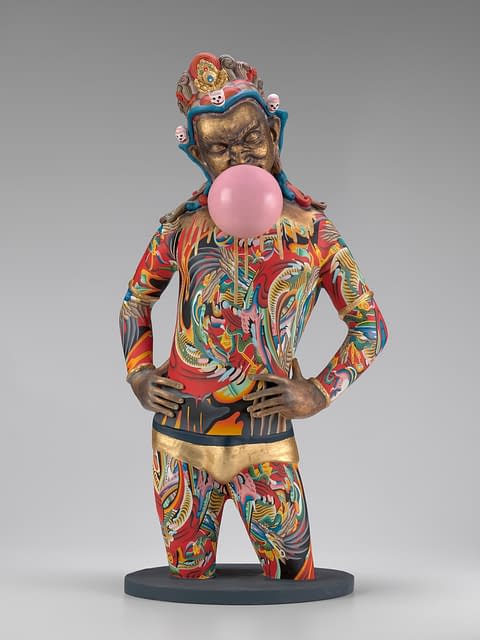

I am greeted by a god. He’s clad in metallic gold briefs, hips cocked like a beauty queen in a swimsuit competition. Pink bubblegum blooms from his scowling mouth. His hands rest on his waist, a gesture that adds to the cockiness, like riding a bike with your arms swinging at the sides, just because you can. But his face is what stops me. Brow wrinkled, teeth gritted, his expression is both aggravated and over it, as if to say This? This bubblegum, this sugar, this small indulgence — this is how you occupy your time? This is the type of distraction you seek? The god has stooped to trying out the pleasures of the material world, but it seems his experiment has yielded only disdain and confusion.

My father walks right past this statue and the two large canvases that welcome us at the entrance of Spirits, an exhibition of works by the artist Tsherin Sherpa at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, which is on view until October. He makes his way into the next room, reading none of the placards, and I wonder if, like the bubblegum-blowing god, he is already bored. In contrast, I read every word, careful to follow the order of the works as laid out, standing in front of each painting and taking it in as if the viewing is an assignment I must complete.

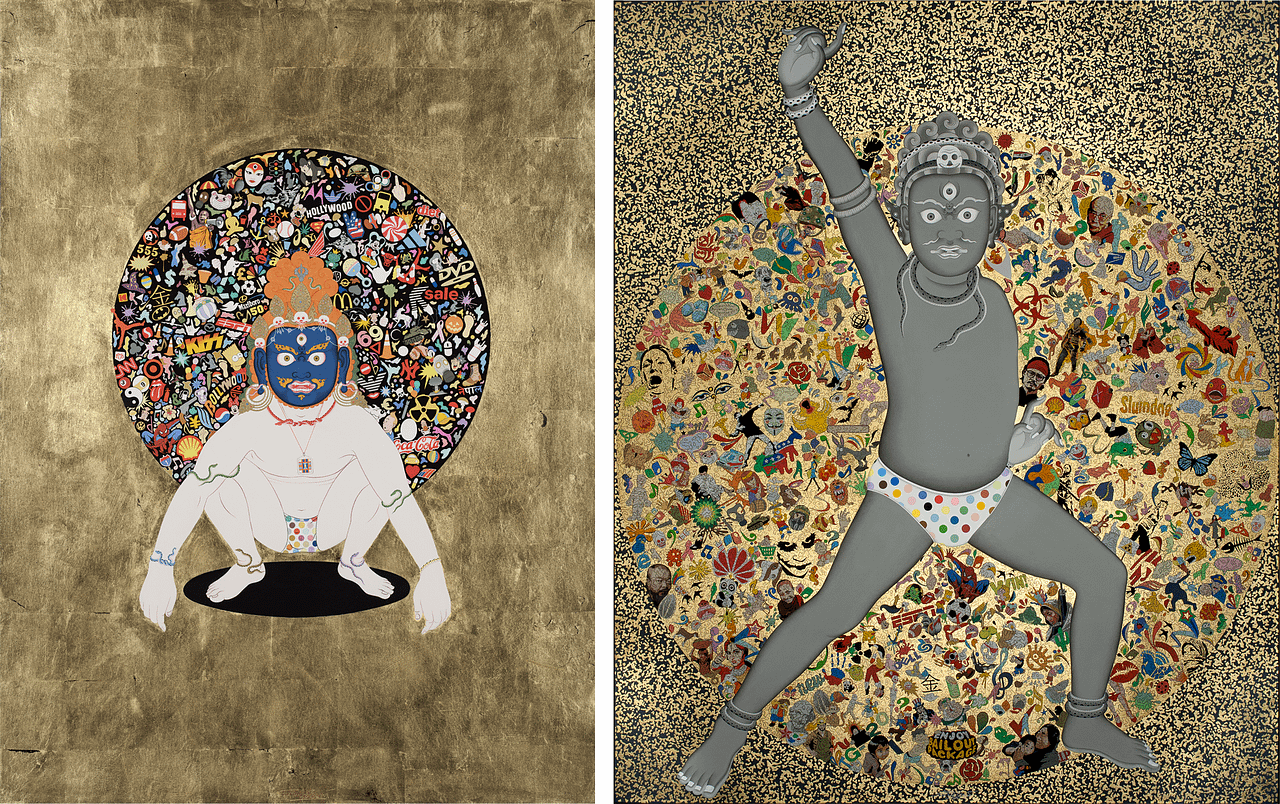

We go on like this. Then Pop wanders back from the fourth section to the second, where I am still lingering. He leans in, arms folded across his chest, and whispers, “The third eye is open. That means it is enlightened,” and I am startled. Third eye? I look up, my very undivine eyes meeting a canvas with two spirits — half-human, half-deity beings — leaping past each other, and there it is on both their foreheads. The third eyes are white, bulbous, as large as the skulls that adorn each spirit’s headdress.

I turn back and notice the eye on the other works I’ve already passed, most of them portraits. In several paintings, the spirit is squatting, buttocks to the ground. In others, the spirit strikes a defiant standing pose: The figure in “Staying Alive (Too Sexy to Die)” — a homage to John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever — appears with one arm aloft, as if caught on the disco floor.

There is something cheeky in almost all the pieces, but Sherpa’s focus is undeniably serious. A Nepali-born Tibetan now based in the United States and Nepal, the artist is interested in issues of dislocation, exile, and cultural dissonance. And while his art may be saturated by pop culture and a neon pastel palette, his craft is informed by older traditions, namely thangka, a Tibetan style of painting in which his father was a master. In the works on display, Sherpa is imagining what might happen if the spirits of a higher realm fell to Earth. What would they encounter? How might they react? And how would they adjust? Witnessing the artist meld ancient and modern worlds, using both ancient and modern techniques, I was reminded of a question that has long occupied me: Is it possible to live a spiritual life while enjoying the pleasures of a material one?

Buddhism and Hinduism influenced the philosophy I was raised in, and both inform the spiritual framework I now follow as an adult. Recently, however, I’ve been considering how the practice and representation of these religions can sometimes feel joyless. There is self-discipline and denial, intense concentration and focus. There are ancient tales of men and women scaling the peaks of the Himalayas in nothing but a threadbare cloth and finding a perch from which to meditate for years, with no thought for food, or warmth, or human connection. There is an understanding that this world we live in, this reality we occupy, is entirely illusory. And to acquire the sight that can pierce that illusion — to open that third eye — one must focus the mind and detach from the material world. I believe in this goal: we must strive for something beyond what we can see. It just doesn’t sound like much fun, does it?

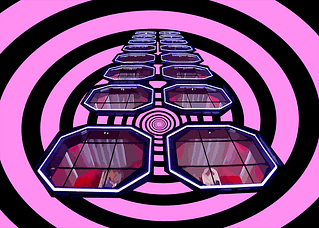

As I wander around the exhibit, I look for clues that might reveal Sherpa’s feelings on my question. Like the gold-briefed god, most of the figures seem at best ambivalent about materialism and modernity. One of the paintings shows a glowering, Atlas-like spirit, with a heavy globe on its back filled with sticker-sized images of company logos and pop culture iconography: Coca-Cola, Bart Simpson, CNN, Bollywood, Spiderman, KISS, Shell Oil, Starlight peppermints, Mickey Mouse, 69, Marlboro, Puma, Playboy, the Olympic Rings, Target, Air Jordan, the empty gas tank icon. The message is clear: These things — colorful and happy and distracting though they may be — are temptations. They fill us and occupy us, but they also burden us. These things tie us down; they keep the third eye shut.

But curiously, among these logos there is also an OM. For me, OM symbolizes the supreme soul, the universal energy that every living entity’s spirit is eternally longing to reunite with. OM encompasses the root logic of my belief system, but I wonder why it is lumped in with those material attachments. The inclusion seems to imply that even spirituality, or religion, or the attempt at practicing either, can be a distraction weighing us down. Perhaps, at times, fervent devotion is no different from material obsession.

A few paintings later, I encounter another work that uses these same logos and symbols — but this time the spirit is in that triumphant standing pose, all those burdens thrown off in a cluster radiating behind it. That’s all well and good — but the figure has lost all its color. In the previous work, the spirit had a deep blue face and sported an orange headpiece. Here the triumphant deity is cast entirely in shades of grey, the only color on its body is a pair of rainbow polka dot briefs. In breaking free of those burdens, why must the spirit almost completely abandon joy?

Left to right: Oh My God-ness!, 2009, gouache, acrylic, and gold leaf on board; private collection, Connecticut. Untitled, 2012, gold leaf, acrylic, and ink on linen; private collection, San Francisco.

And why not indulge in rainbow polka dot underpants? They’re fun! Perhaps the spirit feels this way, too. Perhaps it clings to this last simple pleasure, having forsaken all the rest, as a kind of battle souvenir. And here’s the thing: No matter how unhappy or gray Sherpa’s spirits may appear, the overall effect of all these paintings is fun. That dichotomy is what initially drew me to visit this exhibition. The colors, the poses, the depiction of both innocence and defiance in these half-divinities, rendered so precisely in the traditional style, are all immediately magnetic. While the spirits may not embrace materialism or modernity in a straightforward fashion, Sherpa at least manages to make the divine and the modern cohere in a visual sense.

“This guy,” Pop says, gesturing around, speaking of the artist, “has a lot of thoughts. Many abstract thoughts. Lots of things to say.”

“But what do you think he’s saying?” I ask. I have been watching Pop out of the corner of my eye as I made my very slow rounds. I no longer think he is bored. Once, I see him take out his phone and step back to create enough distance between himself and a large four-paneled work so it doesn’t overflow his camera’s frame. The gallery is almost empty except for the two of us, but each time he steps back, he glances over his shoulder to ensure he isn’t bumping into anyone. That small motion fills me with tenderness; I remember that our time here is fleeting. Pop is almost eighty; his health is ever shifting. A day like this, spent just with him, can be rare. Now, I want to know what he thinks.

“Well, who can know? Who can know but the painter?”

“But what do you think? There’s no right or wrong answer. I just want to know.”

Still, Pop resists me. “Lots of things!” he says, throwing up his hands. “He is a very complex guy. I can see that.”

I think about pointing the wall text out to Pop, instructing him to read about how the artist is interested in themes of dislocation and reorientation, in the small deaths and rebirths suffered internally when one feels pressure to shove their identity into a prefab mold, yet finds they are unable to fully fit into those contours. I consider sharing my thoughts about how, when those deities fell to Earth, they were likely traumatized by the expulsion, but also bewildered by the material attractions they found. But Pop wanders off again, arms crossed, one hand cupping his masked face in contemplation, and I leave him be.

My belief system warns against material pleasures not only because they might become distractions or addictions, but also because the attachment binds you to the world, forcing a return in the next life. Yet in 2020 and 2021, when it seemed the entire globe was pitched into a mental, emotional, and spiritual crisis, I did not often turn to my belief system for comfort. I could barely manage my present life, let alone worry about my next one, and so I turned to things. I spent most of my free time watching television. I binged Chinese and Korean dramas, staying up until 2 A.M. and waking at 8 A.M. to begin my teleworking day. I baked, and I ate a lot. I bought items I didn’t need, and I doom scrolled. I once spent an entire day in bed watching YouTube videos of a man visiting various Japanese vending machines, imagining myself in his place as he pressed the buttons for cake, ramen, or a freshly baked pizza.

These indulgences are not extreme, but they are mine. Looking further inward — when the only thing that remained was my internal monologue, too often terrified and nattering away — was not something I considered doing.

When I look at these divine spirits, who have found themselves back on Earth after being booted out of a higher spiritual realm, I wonder what they did to precipitate their fall. Was it a series of spiritual slips, or was it one single mistake? Was the temptation something initially innocuous, only to reveal itself to be far more dangerous? And if a half-god can make a mistake, what chance do I, or any of us zero-gods, have?

I walk on. One of the larger works in the exhibit is a single giant canvas that occupies an entire wall. Washed in a solid black background, it features two spirits crouching on the ground, observing a few butterflies that flit between them, while a larger cluster wafts above. I’m entranced by the butterflies. They are so luminescent, so exquisitely detailed, that they look as if the artist plucked them out of the sky and coaxed them to lie flat on the canvas.

Spirits (Metamorphosis), 2019–20, acrylic and ink on canvas. Collection of Dolma Chonzom Bhutia.

The body still has to live in the world, be it illusory or real. While living, can I not take pleasure in the sight of a butterfly, in blowing bubblegum, in sneakers and Target sales and Sanjay Leela Bhansali films, and simultaneously not be attached to that pleasure? If we have been banished here like those deities, can we not be allowed to enjoy, just a little bit, even as we work toward enlightenment in whatever ways we can manage it? True spiritual liberation, after all, is a thing to be achieved over hundreds, perhaps thousands, of lifetimes. If indulging in these things results in one additional life, well — so be it.

Pop is waiting for me on a bench by the time I make it to the last painting, but I tell him I want to take one more round. And then I see something I missed. While many of the spirits in the first rooms have bodies all of one color — be it a grapey purple or a fleshy ivory — in the later spaces, the spirits’ skin begin to drip, as if their outer shell is melting upward. Beneath that melting shell, contained within the outlines of the spirit’s body, is a glorious swirl of color, so vibrant it seems to undulate.

I wonder if the problem is perhaps not the things and distractions themselves, but the noise they bring into a life. It becomes harder to hear yourself. But the spirit remains constant. And maybe there is a way to allow the noise but still be attuned to the soul — like isolating the sound of a clock’s tick in the din of a raucous house. If you focus deeply enough, if you can quiet yourself long enough, the self — the spirit — contains wonders waiting to be found, enough to hold its own alongside, and one day surpass, the most dazzling material attachment.

Walking away from the exhibit, I finally just ask Pop my question. He deflected my prodding before, but now there is no resistance at all.

“Enjoy, enjoy! Nothing wrong with that!” His mask is slipping down as he talks, and he yanks it back up, then holds his hands out, one upward-facing palm holding the other hand perpendicular. “It’s just a matter of always being on the edge.” He tips the upright hand from side to side. “As long as you do not go too far over on either side — enjoying the thing to the point of addiction, denying a thing to the point of misery — then enjoy! Enjoy anything your heart desires.”

We are standing in a hall with ceilings twice the height of the exhibit space. There is more light and air in this room, but I’m not ready to let go of the color, the question, just yet. Pop again fixes his mask into place and turns away toward the next gallery. “Don’t think too much.”

We leave the museum and get lunch, sitting at the bar of a crowded restaurant. He gets an appetizer, I get an enormous sandwich, and we split the fries. At the end we each order dessert, an ice cream bar for me and key lime pie for him.

This moment with him, this day, this food — seen from one angle, it’s all its own distraction, I suppose. But equally, my time with Pop is finite. We will all be gone from this earth soon enough, our existence nothing more than a lightning bug’s flash in the dark. I think of him tipping one hand back and forth in the palm of the other. How to balance between pleasure and discipline, how to counter a life lived fully with a soul satisfied, a spirit heard?

Pop scrapes his spoon across his plate to get the last crumbs, his chin cradled in the mask still slung around his ears, pulled down so he can eat. “Marvelous place,” he says when he finishes, pulling his mask back up and rubbing sanitizer over his hands.

We are living in the material world, enjoying these material pleasures. Is the spirit indifferent to these things? Does it accept them with a mild amusement? Does it hanker for them, or feel repulsed, or shake its head and say Again? Surely not again?

On its own, the spirit hums. Perhaps I might learn what mine has to say, if I could only quiet myself long enough to hear it.