On Friday, the Supreme Court of the United States overturned Roe v. Wade— the 1973 ruling that declared a constitutionally-protected right to abortion. Reeling with horror, the Astra Magazine staff reached out to several of the writers we are in touch with around the world to ask for their reactions. Here, Mariana Enríquez, Mieko Kawakami, Leïla Slimani, Katharina Volckmer, and Pola Oloixarac respond.

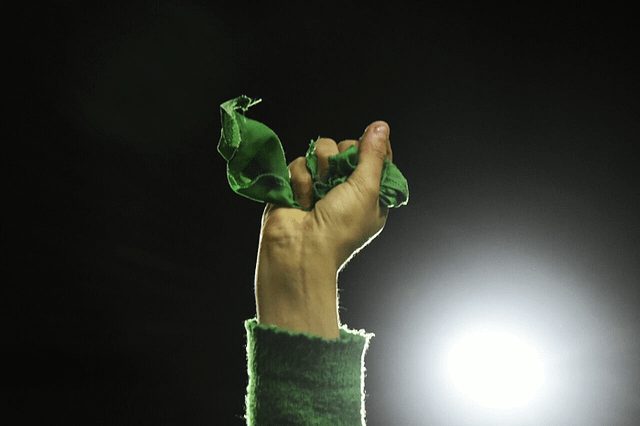

In Argentina, abortion became legal in 2021. Throughout my entire adulthood, abortion was restricted to very particular circumstances — for example, when the mother’s life was in danger. Enshrining abortion in law was the fruit of many years of activism, first from a pioneering group of feminists, and then, in more recent years, from a mass-movement of street protests from women of all walks of life. I’m talking about marches with millions of people, all over the country, who were also protesting against machismo and domestic violence. The abortion law was driven by the President: he knew he had the votes in Congress. (There had been an attempt before, but the vote was lost). It’s a federal law, and although in some of the country’s provinces there are additional roadblocks, due to regional conservatism, there haven’t yet been any serious incidents. As a movement, we always sought to have abortion protected with a law: judicial precedent is notoriously unreliable in Argentina. This is why it has always been surprising to me that in the many years since Roe v. Wade, US politicians have not been able to convert it from a legal precedent, with all the risk that implies, to a statute. Now, I suppose, the only way to achieve this is from the streets. While I don’t know too much about what it’s like to live day to day in the USA, that process seems very difficult. It’s been my experience that every time a nation lurches to the right, it’s very hard to turn back.

—Mariana Enríquez, author of Things We Lost in the Fire (response translated by Samuel Rutter)

Women’s bodies are in danger. Black bodies are in danger. Migrants’ bodies are in danger. The bodies of the poor are in danger. These are our bodies, which are being offered up to rampant liberalism. And if the conservatives sees the overturning of Roe v. Wade as the triumph of God’s will, it is in fact the triumph of the God of money. The God of money that allows Boris Johnson to sell Ukrainian migrants to Rwanda. The God of money that decrees that tomorrow, impoverished women will no longer be able to access abortion services while those with means will be able to travel to states that permit it. Impoverished women who, because of an unwanted pregnancy, will slip further into poverty, making them more likely to abandon their studies, to accept precarious employment, to be victims of violence. Women who, despite it all, will still attempt to have abortions and will die in the process, as happens to one in nine women around the world. No law that can be evaded with money can be a just law.

I’m going to tell you some dark stories. I’m not going to tone it down for you sensitive souls, because in a country where abortion is illegal, every story about abortion is a dark story. In Morocco, where I’m part of an activist collective working outside the legal system to decriminalize abortion, these kinds of stories are part of daily life. Six hundred clandestine abortions are practiced every day. It’s the story of Latifa, a primary school teacher whose fickle husband cheats on her with a nineteen-year-old girl. He promises the girl marriage and a bright future. But the young woman falls pregnant, and the husband, fearing a scandal, takes her to a back-street abortionist — an “angel-maker” as we say in French — and she dies there from a hemorrhage. It’s the story of Jamila, a domestic servant, who is raped by the custodian and doesn’t dare tell a soul about the crime. Jamila hides her pregnancy from her family and her employers, who one morning, find the body of an abandoned baby in a trash can at the end of the street. It’s the story of a doctor who approaches me one day in a restaurant in Meknes. A man whose face is creased with worry, who hands me a letter and disappears. In it, he writes that he and his nurse have spent ten years in prison for performing illegal abortions. His whole life, he has tried to come to the aid of desperate women and to offer them a way to decide their own futures.

The decision by the Supreme Court is a tragedy for American women, but not just for them. It sends a terrible message to everyone who is fighting to make abortion legal. Tomorrow, this new American reality will be one more excuse for those who oppose abortion. We’ll see that even those who usually dismiss the USA as a country ruined by wealth and decadence will find a way to use this example to their advantage. If even the world’s biggest democracy has banned abortion, why shouldn’t we? We must remind those people that there can be no true democracy, no true citizens, in places where individuals can’t make decisions about their own bodies. We must stand up for all of these injured, imprisoned and diminished bodies. We must wake up now, because our enemies are powerful.

—Leïla Slimani, author of In The Country of Others (response translated by Samuel Rutter)

Abortion is illegal in Japan, but it’s possible to get a procedure under the Maternal Protection Law if certain conditions are met. However, consent is required—consent of the parent if the woman is underage, consent of the spouse if she is an adult, or the consent of the “partner” if she is raped. Moreover, morning-after pills are not accessible over the counter because pills apparently make women, as ignorant beings, promiscuous. Surgeries are performed using the curettage method which induces pain and can only said to be punitive. On top of it all, there is the ludicrous fact that the age of consent in Japan is thirteen years old. I am stunned and disheartened at the U.S. Supreme Court decision. In the U.S. and in Japan, judges are almost exclusively male. The decision sends a clear message that women’s bodies belong to male authority and to the state—that women should not live as individuals but are first and foremost child bearers. This is a huge mistake, and we must not accept it. My body belongs to me. This is the fundamental principle of human existence.

—Mieko Kawakami, author of All the Lovers in the Night (response translated by Hitomi Yoshio)

Abortion was legalized just a few years ago in Argentina, after years of congressional debates: one of the arguments that overcame the polarization was that reproductive rights for women were the norm throughout the developed world. It’s sad and weird to think that America is suddenly closer to Iran than to the UK or France. Decades of legalized abortion has shown a decrease of criminality in impoverished areas (I think Rudy Giuliani has those numbers somewhere)…do the pro-life people care about those unwanted babies once they grow up? State-run misogyny is a political problem, not a biological one. Millions of embryos are created everyday via fertilization techniques and there seems to be no shortage of the human animal. I’m positive that American women will prevail, and we must do everything we can to support them.

—Pola Oloixarac, author of Mona

Bodies that can give birth don’t own themselves. They are owned. By the structures they are born into. By the laws that surround them. By those men who are scared of what’s inside those bodies. Of the wombs and the power they hold. It’s fear that drives these structures of violence, the knowledge deep down that you only try to contain that which is more than you. Not less. I don’t always think of myself as a woman, the word doesn’t carry a lot of meaning for me. But my body also holds that miracle. The womb that leaves me subject to oppression. To the violence that stands between us and the world. Between us and our freedom. Between us and the end of our fear. We have to be able to choose our bodies because a body owned by the state can never be at peace. And we need peaceful bodies that can move with grace. Now more than ever.

—Katharina Volckmer, author of The Appointment