The workers came and destroyed the outer walls. The brick wall fell apart like a cake demolished at random by a child with a fork. The next day, the garden was revealed.

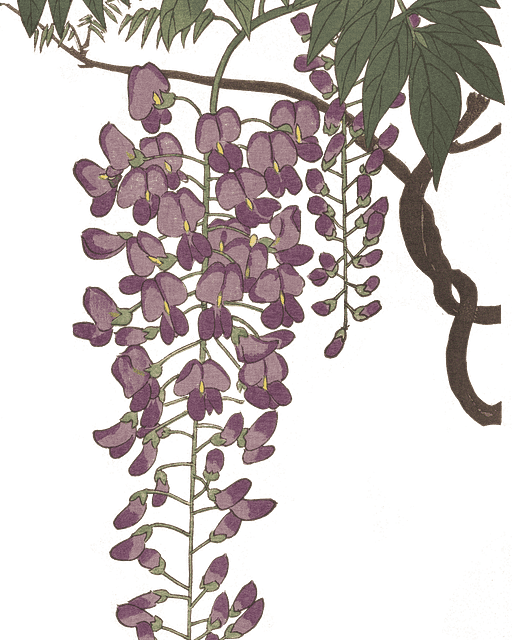

The wisteria tree, the one whose flowers bloomed behind the walls every spring, could be seen in its totality. Its dark trunk seemed thicker than the branches had suggested, and next to its roots was a pond in the shape of a gourd. The water had already been drained, and old, colorless leaves covered the bottom. Behind the pond was an old-fashioned porch. When the small yellow excavator came the following day, it made a low, angry growl and started digging up the garden.

It took only thirty minutes to cut down the wisteria tree. Its roots, abandoned on the dirt, resembled arms that grasped at something in midair. The excavator crushed everything, mixing the laundry pole, the flowerpots, and the stones. It trampled the porch and bulldozed through the house, mercilessly clawing through the furniture and screen doors. So that’s how you destroy a house, I thought, half-amused and impressed. The old two-story house that had stood majestically in the corner lot diagonally across the road was being destroyed, and I was watching the spectacle from my second-floor kitchen window.

An old woman had lived there. I would sometimes see her. When we moved into the neighborhood six years ago, we tried to pay a visit to the house a few times, but no one ever answered the door. Every once in a while, I would pass the old woman on the street as she walked slowly around the house in the morning and evening hours, leaning against a cart. We never exchanged greetings, and yet I felt strangely serene in those moments. She always wore a black blouse with a black cardigan draped over her shoulders, and in the spring evenings, I would see her walking slowly out of the rusted gate onto the sidewalk with a broom and dustpan in her hands. When the wisteria tree shed its flowers, the gray asphalt would be covered in shades of white and pale purple, and every time the wind blew, the petals would dance in the air. The old woman would spend a long time sweeping up those petals from one corner of the road to the other. The petals fell even on seemingly windless nights, and the following day, the old woman would emerge slowly with her broom and dustpan again. This would continue until the flowers were gone. But I had not seen her recently. When was the last time I saw her?

“I wonder if that old woman passed away,” I mentioned during dinner one night.

After a pause, my husband grumbled something inaudible, his eyes still fixed to the TV screen.

“They’re doing work over there. It’s been so noisy.”

“Hmm. Looks like they’re demolishing the house,” he said.

I stacked my own dinner plates and took them over to the kitchen sink. I watched as my husband nibbled on his vegetable stir-fry while sipping a can of beer, laughing soundlessly at the TV.

It had been nine years since I married my husband, who was three years older. I had been twenty-nine at the time, and he had been thirty-two. Three years after the wedding, we bought this house. My husband had a job in the sales department at an international pharmaceutical company, and every morning, he left for work at eight o’clock. After seeing him off, I would sweep around the house and water the grounds, put the towels and sheets in the laundry machine and press the start button. I would vacuum the living room and the other two rooms. At eleven thirty, I would eat a simple lunch, then walk to the supermarket near the station to buy groceries. My husband hated the fridge being full, so I went to the supermarket every day to buy only the things I needed that day. Our fridge was always empty.

I would scrub the kitchen methodically and wipe down the windows. Around six, I would make dinner and eat on my own. I would turn on the TV, then I would turn off the TV. Around ten, my husband would come home. I would heat up his dinner while he took a shower. My husband sometimes told lies. He would watch late-night TV shows while sipping beer and eating, then crawl into bed and stare at the pale screen on his smartphone for a long time. Every morning, my husband would wake up with dark circles around his eyes. He would slump his body against the door and leave the house.

We started considering having children around the time we bought the house, and for a while we tried. But I didn’t get pregnant—which was a possibility I had never considered. With no preexisting condition and regular periods, I had assumed that it was all a matter of timing. But six months passed since I had begun taking my daily temperature, then a year, and still nothing happened.

After some online research, I realized that we were already at a stage when we needed to begin treatment at a specialized clinic. For two months, I buried myself in books about fertility treatments in the library and scoured the internet. I felt a wave of anxiety that my body had perhaps already lost the ability to conceive. One thing was for certain—if I wanted to get pregnant, I needed to start treatment as soon as possible. And for that,

the understanding and cooperation of my husband was crucial.

One evening, I brought up the subject with my husband. I suggested that we go to a clinic together to find out why we weren’t getting pregnant, and that both of us needed to be examined. I chose my words carefully and explained as best I could.

My husband was clipping his toenails. Looking up, he furrowed his eyebrows and made a disgusted expression. That expression. It felt as if I were being stabbed with something sharp between my lungs every time.

“What do you mean, examined? It’s not like you’re sick, are you?”

“It’s not about being sick,” I answered carefully. “My period comes regularly, but it doesn’t mean I’m ovulating. And even if I were, I still need to make sure the eggs are functioning properly.”

“We need to go together,” I continued without looking his way. “We’ve been trying for a year now and nothing has happened, so there must be some reason . . . We won’t know what the problem is until we’re both properly examined.”

My husband threw the clipped nails into the trash can. Then he stared off into space at the white wall. After some time, his cell phone began to ring. “It’s my business partner . . .” he muttered under his breath and left the living room to go downstairs. I heard him say hello as the door closed behind him.

He brought up the subject again one night, two weeks later, after the bedroom lights had been turned off. “About that clinic you were talking about . . . I think we should just let things take their course.”

I remained silent.

“They say children are a blessing—not something you force. And there’s no end to fertility treatments once you start. People spend ten million yen and still get nowhere. Plus, it’s not like we desperately wanted one, right?”

My husband’s voice assaulted me in the darkness, coming at me like the index finger of a relentless auditor that scrutinizes product defects. I kept my eyes open in the dark, thinking about the pain in my chest. After a while, he seemed to have fallen asleep.

From that day on, we never talked about having children again, and my husband stopped initiating sex. Before long, I was thirty-eight and my husband was forty-one.

It was during the last week of March that I noticed the sound had stopped. I had assumed the demolition work was put on hold due to rain, but come to think of it, there hadn’t been any rain in a while. Looking through the kitchen window, I could see the house still in the process of demolition, only about a third of the way through. When had they stopped?

I listened but there was no sound. It was so quiet. What did people around here do this time of day? Who on earth were these “people” anyway? Even the next-door neighbors were strangers—I knew nothing about them aside from their general family compositions and the colors of their cars. After observing the house for a while, I went down the stairs, put on my sneakers, and went outside.

Although it was only March, the sun beat down and made me sweat under my thin sweater. The house lay exposed and immobile beyond the rubble. I had passed by countless times since the demolition began, but this was the first time I stopped to examine the house carefully. It looked much larger than it had from my second-floor kitchen window.

Pieces of broken debris gleamed sharply in the sun, and the paint can that the workers had used as an ashtray was buried halfway in the dirt. A heavy shovel lay abandoned on the ground. A glove was stuck to a wooden plank, and glimmering shards of glass mingled with the dirt and debris. Dry white mud caked the caterpillar track of the excavator, its scoop still filled with dirt as if it had lost its way in midair.

I must have been gazing at the house for five or ten minutes when I felt a presence and looked up. There was a woman standing on the left-hand side of the property, where the gate and entrance used to be. She was about my height and wore a long-sleeve black dress. Her arms, which hung by her side, seemed disproportionately long. She was staring at the house, just like I was.

“No sign of rain,” the woman said. Then she slowly made her way over to me until we were standing side by side. She seemed to be around my age. Her face, with no trace of makeup, was covered in spots, and her forehead seemed shockingly narrow against her thick black hair, which was tied back. Her hands were empty.

“I’ve been coming here since they started the demolition,” she said.

“I live just over there,” I said, pointing to my house.

“Doesn’t the noise bother you?”

“Not too much,” I responded.

“I wouldn’t be able to stand it. You know, that peculiar sound.”

“Peculiar sound?”

The woman nodded, her face still turned to the house. “The sound of something being destroyed.”

The sound of something being destroyed . . . I gazed at the house before me but couldn’t recall any particular sound from the past few weeks.

“But aren’t there all kinds of sounds?” I asked. “Depending on the material. . .”

“Material?”

“Yes, well . . . glass would make a different sound from wood, right?”

“That’s not what I’m talking about. Whatever the material or size, there’s a kind of essence of sound that can be heard only when something is being destroyed. It’s like catching a single note within a chord. I can hear it mixed with other sounds. You can detect a sort of intention.”

“Intention?”

“I’m not sure if it’s the intention of the destroyer or the destroyed, but I can hear it. It makes a world of difference whether something is destroyed naturally or by external force.”

I had difficulty comprehending what the woman was trying to say. As I searched for words, she took a step into the property and began walking toward the house.

“I’ve never been here during the day,” the woman said after some time.

“During the day?”

“I usually go into empty properties at night.”

“Empty properties?” I echoed with surprise. “What do you mean?”

“An apartment, a condo, a house. It doesn’t matter what kind, just as long as it’s empty.”

“Why at night? So you don’t get caught?”

“There’s that. But I really like houses at night.”

I thought to myself, It must be so dark . . .

“Of course,” she said, as if she had read my mind, “the circuit breaker is switched off, so it’s pitch dark. I enter the darkness and sit in the living room, or in the center of the room if it’s a studio. Then I lie down and open and close my eyes slowly. The eyes adjust after a while, and you start to see all kinds of things. Light finds its way in even at night, no matter how small the window may be.”

I imagined the woman opening and closing her eyes in the dark.

“Yes, like that. I lie in the room for a while. Then, I leave.”

“What about the keys? How do you find these empty properties in the first place?”

“Real estate agent websites. I look through their rentals. Expensive properties are no good since they tend to have tight security. Same with upscale condos with a front desk. Old buildings are best, especially if the apartment has been sitting for a month or two since the listing. You can usually find the keys taped to the top of the mailbox, or attached to the side of the pipe closet or the meter box. Or they could be sitting on top of the gas meter. If I can’t find the keys, I just give up. One in three, I find a way in.”

I tried to imagine an abandoned house in the middle of the night. No furniture, no human breath, just darkness alone. Then, light finds its way through the windows, eroding the room in shades of blue. A woman’s arms, plump with blue shadow, slowly extend toward me. I looked up.

The woman was still gazing at the house.

“Did you go inside this one?”

The woman shook her head. “I came as soon as I heard about the estate sale, but the demolition work had already started. It’s not every day you come across such a large house, so I was quite disappointed.”

We fell silent and gazed at the house together.

The woman with the long arms looked up. “Smells like rain,” she said

From that evening, it rained for two days straight.

I vacuumed every corner of the house with more care than usual and scrubbed the floors with a tightly wrung towel. The rain turned into a downpour, and the wind blew against the windows so hard it seemed like someone was running across them. I listened to the low tremor of thunder in the distance.

My husband came home late. “I’m entertaining clients this weekend,” he grumbled while watching TV. His boss had come down with a stomach flu, so he would have to take them golfing instead. It would be an overnight trip. “We’re going to the hot springs and it’s not even winter,” he complained. I listened half-heartedly while doing the dishes, then leaned against the cupboard and looked out the window. Beyond my own face reflected on the dark murky window, the house stood in the depth of the night.

The darkness, the desolate sound of the winds, the low growl of thunder, the unceasing rain—everything seemed to flow out of the house like a wound, half-destroyed and laid bare. The rainwater came alive as it made its way down the gentle slope below. I pressed my fingers on the glass as if to touch the movement—then noticed my husband’s voice.

“Are you listening?”

“Sorry,” I said. I hadn’t heard a word he said.

Early Saturday morning, my husband loaded his golf bag in the car trunk and drove off. I finished the housework as usual and waited for night to come. Three days had passed since the torrential rain. The sun moved slowly across the sky, and as the dusk melted into asphalt and trees and houses, darkness fell. A dog barked. A young woman talked into her cell phone. A motorcycle drove by, its engine blasting. Then the sounds ceased. At one o’clock in the morning, I left the house.

Small puddles remained in what was once the garden. My whole body felt stiff, and I could feel my back starting to sweat. I advanced little by little, holding my breath. The closer I got, the farther the house seemed to move away from me. When I looked back, I saw a faint round light. It took a while for me to realize that it was the entryway light to my own house.

The tatami mat was dry, thanks to the half-remaining roof. I took off my sneakers with some hesitation and placed them inside what must have been the living room, now half-destroyed, and proceeded to go farther on my hands and knees. When I came to a pillar, I stood up and passed the alcove I had seen from afar, then continued to tread with caution toward the right-hand side.

It did not take long for the shapes to appear on the tatami mat, like a hidden pattern in a trompe l’œil picture. Worn pencil with the eraser still attached. White coffee cup. Large wall calendar covered in cloth, caked with mud. Magazines with pages falling out. Grand prize shield with gold plates. A cord, perhaps. An entire drawer overflowing with sheets of bundled paper. And then there was a set of two dark-colored sofas. Behind them were a shelf and what looked like a record player. I advanced slowly while studying these objects one by one, and eventually reached a narrow corridor that led to the interior of the house.

In the corridor, the blue light that had filled the room until a moment ago receded, and a thick darkness of an entirely different quality engulfed me. The darkness became thicker as I inched forward, and my heart began to make a drumming sound. Eventually the corridor came to an end, and my toes touched a doorsill on the left-hand side. Extending my feet, I could feel carpet. Here’s another room. When I swallowed the saliva that had accumulated in my mouth, it made a sound so loud my body shook. I took a step into the room.

The room was filled with profound silence and darkness. I could no longer see myself. Shouldn’t I go back the way I came, crawling on all fours, to return to a place where there is light? Suddenly overcome by fear, I felt my heart beat faster. I realized then that I had no water with me. I wetted my lips several times. My mouth felt dry. I took a deep breath, telling myself to calm down. My house is on the other side of the street. If I get thirsty, all I need to do is go back. Everything will be all right. But was it true? Did such a place—a home to go back to—really exist?

My eyes showed no sign of adjusting to the dark, no matter how long I stood there. The darkness seemed to exclude light altogether. And yet I kept walking farther into the room. The living room was strewn with countless objects, but this room was different. I could feel the carpet under my feet and nothing else. Taking three more steps, I lowered my body and fell to my knees. I placed my hands on the carpet and gradually moved them outward in a stroking motion, as if drawing small circles with my fingers. Still nothing. Then slowly, I leaned back and lay down. As I relaxed my limbs and lay still, the boundary between myself and the darkness became more and more ambiguous.

What kind of room was this?

I couldn’t make out the color or pattern of the carpet, nor was there anything peculiar about the texture. It was impossible to tell how big the room was or how it was arranged, whether it was a Japanese-style or Western-style room. Was it a bedroom, perhaps, or a study, or a children’s room? A storage room, or even a walk-in closet? I imagined the old woman with her white hair pulled back, hunched over a cart and walking slowly around the house, meticulously sweeping the fallen wisteria petals. Where did she spend most of her time in this large house?

I realized I knew nothing about the old woman, not even her name. I tried in vain to recall the name plate in front of the house. Could she have been eighty years old, or perhaps even ninety? It was hard to guess the age after a certain point. How long had she been living alone? The house seemed much too large for one person to occupy. When I tried to picture the house, however, I realized I couldn’t even remember what it looked like.

What I could recall was the exterior wall, made of reddish-brown brick that you would see anywhere. Standing behind it was the wisteria tree, which had the most exquisite color. I would often gaze at the hanging flowers from my kitchen window or from the street on my way to and from the store. Next to the large rusty iron gate hung a well-worn placard for an English-language school for children. The sign was difficult to read due to rain and wind damage, but one could make out a foreign name written in large katakana letters. And beside it was a Japanese woman’s name. MS. ** WILL TEACH YOU ENGLISH, the sign had stated proudly. But what was her name?

I tried to imagine the old woman as a young teacher, giving English lessons to a small group of children. Enveloped in total darkness, my imagination was strangely vivid and raw. She is in her mid-thirties. Her thick lustrous black hair pulled back, she peers into children’s notebooks while resting her hands on their desks and checking for mistakes. From time to time, the foreign teacher pronounces the words in English, opening her mouth wide so the children can see the movement of her tongue. Seals. Owl. Umbrella. The children, having just entered primary school, repeat the English words. The foreign teacher smiles and reads aloud the next set of vocabulary. She is some years older than the old woman. Two dimples are visible on her red cheeks against her pale skin. Her hair, so blond that it looks white depending on the light, is cut short, and she towers over the petite old woman by at least half a foot. Whenever they were in the classroom, the two women always wore black blouses in various types of fabric. They never made a conscious decision to do so, but it became a kind of unspoken agreement.

The foreign teacher arrives at ten o’clock in the morning. Over a hot cup of tea, the two women go over the lesson plans for the day, followed by lunch at the kitchen table. Sometimes the old woman would make thin wheat noodles, and other times the foreign teacher would bring simple sandwiches. After clearing away the dishes, the foreign teacher would listen to a record in the living room. On that particular day, she brings over her favorite record and invites the old woman to listen as she carefully places it on the turntable and drops the needle. They sit side by side on the small velvet sofas and listen. Piano Sonata no. 32, second movement—Beethoven’s final piano sonata. The old woman closes her eyes. Listening to the soft and soothing voice of the foreign teacher as she talks about the piece and the female pianist performing it, the old woman experiences an inexplicable feeling, at once dark and happy, like an endlessly spreading gray sky. Over the years, they would listen to the piece over and over, more times than they could count.

The children are generally quiet during lessons, writing neatly in their notebooks with their pencils. Aside from the girl sitting by the window who has a habit of letting her eyes wander, the students are well behaved for the most part and listen attentively to the teachers. The classroom is on the upper floor of the house in a large Western-style room with a wooden floor, and different students occupy the room depending on the time and day of the week. Saturday afternoons were reserved for upper primary school children.

Does one of the children belong to the old woman? Probably not. Since her father passed away about ten years ago, she has lived in this house alone. She was brought up by her father, in this house that had escaped war damage, and aside from the absence of her mother, she lived a privileged life and received an excellent education. She never married. Her father’s efforts in matchmaking were in vain. The old woman loved the English language, and by the time she was fifteen years old, she could read simple novels in English. In college, she studied modern British literature and fell in love with Virginia Woolf. Clutching her dictionary, she would try to decipher Woolf’s complex sentences, which seemed to weave together a beautiful tapestry with shadows falling here and there, never repeating the same pattern twice.

One day, the old woman met the foreign teacher in a small reading group. The foreign teacher told her all kinds of stories about the town of Chelmsford, where she grew up. She also told her about London—about the air raids, Westminster Cathedral, the fountain of St. James’s Park and how the light would dance on the water, the coronation ceremony of Queen Elizabeth II, the curse of London Bridge. It didn’t take long for the two to become best friends. And one year later, the two women decided to open an English-language school together, in the house where the old woman had been living on her own since her father passed away.

The wisteria tree had stood in the garden since long before the old woman was born. Every year, the tree blossoms with flowers, gently swelling into pale pink and purple clusters as if inhaling the dreams of dawn. In springtime, the two women would sit side by side on the porch between classes and look up at the tree. “Wisteria,” the foreign teacher would sometimes murmur, as if filling the blank space between herself and the flowers. That day, as they sit gazing at the wisteria tree side by side like always, the foreign teacher suddenly asks the old woman if she could call her Wisteria.

“Sure. But why?”

“Everyone has a real name. I can guess what it is. After knowing someone for a while, I start seeing the name appear in the middle of their face. I figured out soon after I met you that your name was Wisteria.”

Wisteria, the old woman whispers in her mind. Wisteria. The name, with such a foreign ring, tickles her and makes her blush. She tries saying it aloud. “Wisteria.”

At the foot of the wisteria tree is a pond shaped like a gourd, with a few medium-size carp swimming in it. The pond shimmers every time the wind blows, and if one watches the movement of the water, it seems possible to touch a soft part of some distant forgotten memory. On especially windy days, the petals would fall and cover the water in white, and the two women would scoop them up endlessly with their nets.

One spring afternoon, the third spring since they started their English-language school, the foreign teacher loses her balance on the edge stone and falls into the pond, taking along Wisteria, who instinctively grabs her hand. Seeing each other sitting in the pond, the two women burst out laughing. Clothes soaking wet and covered with petals, water dropping from the tips of their hair, softly shining in the light. Seeing the foreign teacher laugh makes Wisteria laugh, but after a while she becomes aware of emotions she has never known before. It isn’t pain or aching or sorrow exactly—whatever it is, that shadow engulfs her and makes her look away from the brilliance before her.

The two women would finish their work around seven o’clock in the evening. Then, it would be time for the foreign teacher to leave. Sometimes they would have dinner together at the house, and other times, they would walk down to a soba shop near the station. No matter how late it is, the foreign teacher never stays the night. The two always wave goodbye at the entrance of the house or by the train station.

From the living room, Wisteria would walk through the corridor to reach her bedroom. Unlike the sunlit living room and garden which faced south, the north-facing bedroom seems to exist in a perpetual bluish shadow, remaining cool even at the height of summer. The nights are especially long. Turning off the light, Wisteria would lie on her back in the darkness and breathe in and out. “Drop upon drop, silence falls . . . As silence falls I am dissolved utterly and become featureless and scarcely to be distinguished from another.” Wisteria stares at the words that suddenly came to her, blinking in the darkness. Ah . . . it was Woolf. The waves rushing to the shore, eternally, yet never to return. “In this silence . . . it seems as if no leaf would ever fall, or bird fly.” The characters whisper. “As if the miracle had happened.”

Wisteria imagines the doorbell ringing—with the force of a prayer, she imagines it ringing. She rushes out of her bedroom and heads for the entrance. When she opens the door, the foreign teacher is standing there.

“I left something behind,” she says with a shy smile. Wisteria takes her hand and invites her inside. She is on the verge of tears, overcome by the feeling of ecstasy upon touching her beloved’s body for the first time. In silence, the two join their bodies together. Wisteria slowly extends her arms. Holding her breath, she stretches her arms straight before her. But the only things her fingers touch are the cold lonely particles of darkness that fill the room, where she lies all alone.

There is no doorbell. There is no miracle.

The days pass uneventfully. Wisteria is not released from her nightly suffering. She lies on her back in the bedroom, her hands placed on her stomach, waiting for sleep to take her away from the here and now. But she is wide awake.

In the darkness, Wisteria clenches her hands, which rest on her stomach. She closes her eyes, then opens them again. I never gave birth. At thirty-eight, it is the first time that she puts the thought into words. She finds the thought almost comical, after all this time. She has never touched a man, even held hands, never felt any romantic feeling whatsoever. It seems humorous somehow that someone who has never desired nor been desired would think of such a thing as that.

But that evening, the thought of a child captures Wisteria’s imagination and does not release her. What does it mean to give birth? How does it feel to have a baby grow inside your body? Staring into the dark with these thoughts, Wisteria begins to hear a faint cry coming from somewhere. It is a baby crying—Wisteria is sitting on a sunny porch, cradling a tiny baby in her arms. The baby has the same color hair as the foreign teacher, so blond that it looks almost white in the sun. Wisteria knows instantly that this baby, clasping its tiny wrinkled hands next to its mouth, belongs to her and the foreign teacher. How or where the baby came from, she doesn’t know. But she knows it is their baby girl. A feeling of love rushes forth from within. Our daughter. Wisteria gazes and gazes at the face of the sleeping baby, places her gently in the basket so as not to wake her, and closes her own eyes to succumb to a warm afternoon slumber. When Wisteria awakens, the baby is gone. Inside the basket, only the blanket remains with the baby’s imprint. She screams. She realizes, then, that she is lying on her back in a profound darkness that was even deeper than before.

Her heart beats fast. The tears crawl around her temples to the back of her head like a living thread. They wrap around her neck and strangle her. In the darkness, Wisteria tells herself, The baby doesn’t exist. Nowhere in this world does the baby exist. There’s no such thing as our baby. Even if we were to act on our love—though it would never happen—we still could not have a baby girl together. Because I am a woman, and she is a woman.

One day, the foreign teacher departs. Her mother has fallen ill, and she needs to return to England to take care of her. “I love this country. I love our work together. I’ll be back as soon as things are settled. In the meantime, I can introduce you to someone who can teach the children on my behalf.” Wisteria shakes her head and says she’ll try to manage on her own. It is the tenth spring since they opened the English-language school together. The wisteria tree has flowered beautifully this year, as always. The two women sit side by side on the porch, watching the petals fall one by one on the surface of the pond and on the warm soil of the garden.

“Do they have wisteria trees in England?”

“Of course. Lots of them,” the foreign teacher answers.

In silence, they gaze at the wisteria flowers together. Then, after some time, the foreign teacher says, “I had a child once.” Wisteria looks at her face as if struck by lightning. The foreign teacher keeps her eyes on the wisteria tree and continues in a low voice.

“I don’t have one anymore. The baby died. It was a long time ago, almost thirty years. The baby lived for only three months.” She exhales and looks over at Wisteria’s face for the first time, smiling faintly.

The foreign teacher leaves for England. Wisteria receives letters from her twice a month, which becomes once every two months, then once every six months, then eventually a Christmas card once a year. Perhaps that was all to be expected. They were close friends who trusted each other and worked together for a decade, but they had never made any future promises to each other.

One day, after the same number of years had passed as they had spent together, Wisteria sits down and writes a letter with singular hope. Although the two have grown apart, Wisteria wishes to see the foreign teacher again even just once. It is unlikely that she would return to Japan. So why not travel to England herself? Wisteria has never traveled abroad in her life, but if the foreign teacher were to reply with the words, It’s been so long. How are you? It would be lovely to see you again, then she feels she could do anything. Wisteria worries about how much she has aged, being already near seventy, but more than that, she is moved by the strong desire to see the foreign teacher again. She spends many days writing the letter.

But no reply comes. Wisteria waits a month, then six months. She does not receive a Christmas card that year. Had she written something to offend her? Or was the letter itself unwelcome? Wisteria thinks of all the possibilities, but there is no way to find out the truth. Wisteria spends the winter full of anxiety and depression, but as winter gives way to the fragrance of spring, filling the air, a letter arrives. One afternoon, Wisteria sits on the porch amid the falling petals and reads the letter from England. It contains news of the foreign teacher’s death. “I was her colleague,” the letter explains. “She had lung cancer, and by the time she was diagnosed, it was too late. She died within three months. This past spring. There was a will, but it contained mostly administrative matters. There was no mention of you. I’m writing to you of my own accord because I found a stack of letters from you when I was organizing her belongings. I thought it best to let you know. Please don’t take it hard. She went to heaven without suffering.”

Wisteria closes the English-language school and begins spending her days alone in the house. She wakes up in the morning, gets dressed, and spends a long time cleaning the house. She goes to the kitchen and scrubs all her unused pots and plates and wipes down the inside of the empty refrigerator. Before dust has a chance to settle, she dusts all of the furniture and sweeps the tatami mats. She keeps sweeping the invisible dust with a broom as if caressing the traces of time that has passed.

That was when Wisteria was still able-bodied. After a while, her consciousness begins to shift shape and change color, and her body becomes so weak that she can no longer leave the bedroom. Darkness torments her without mercy. That day the letter arrived replays endlessly in her mind. It is spring. As wisteria petals scatter like snow in the wind, Wisteria learns the news of the foreign teacher’s death. A single image whispers its presence to her once again, one that had visited her repeatedly since the foreign teacher left. It is the baby—dead three months after it was born. It’s all my fault. Wisteria opens her eyes in the dark. The baby died because I wished for a baby together and held it in my arms.

It is illogical, of course. The foreign teacher’s baby had died long before they ever met, and time would have to be reversed for the two events to connect. But Wisteria understands. She had felt emotions she was forbidden to have, desired what was not meant to be desired. She had caressed the baby’s fair hair, which did not exist, and brought her face to its soft cheeks and inhaled its gentle breath. And for that, the baby was lost. Please don’t take it hard. She went to heaven without suffering. The wind blows. It is as if all the winds in the world come gushing toward Wisteria. The wisteria tree shakes, and the petals turn into a whirlpool that engulfs her. She cannot see. She cannot breathe. In the darkness, resting her withered hands on her chest, Wisteria thinks these thoughts as she takes her final breath.

I have been here from the beginning. I have been here all along.

I opened my eyes and blinked several times. I slowly exhaled the air that remained in my chest, then breathed in again deeply. My body felt heavy, and I could barely move my limbs. My head throbbed. There was a piercing pain in my hips. I had no idea how long I had been lying there. My body ached with a distinct sensation that signaled an oncoming fever. A chill ran down my back, and my breath felt hot.

My mind, on the other hand, felt eerily acute. When I opened my mouth, my back teeth stuttered. It was cold. My entire body ached with grating pain. As I sat up slowly on the carpet and rubbed my shoulders, I came upon a realization. The texture of the darkness had changed.

Ever since I entered, the room had been filled with an impenetrable darkness. I had become part of that darkness and the darkness had become part of me. But now it was different. The darkness had transformed into a bluish shadow that gently illuminated my arms and thighs and feet.

Light finds its way in even at night, no matter how small the window may be. It was just as she had said.

I don’t remember how I left the house, walked across the muddy grounds littered with debris, and arrived home. Countless large raindrops pelted my body. I took off my sneakers by the door, went up the stairs straight into the kitchen without turning on the light, pulled a glass out of the cupboard, and drank two glassfuls of water from the tap. I grabbed a towel and wiped my face and hair, which were both dripping wet. My body wouldn’t stop shaking.

“Where were you? Do you know what time it is?”

There was a dark, sunken figure on the sofa in the living room. It was my husband.

Resting my weight against the sink, I stared at my husband’s shadow floating in the dark. Why is he here? But I no longer cared. He floated there in the darkness like an obscure lump of shadow. Looking at the lump, I realized I could no longer remember his face. Who is this man?

“Can’t you answer me?”

I could sense him standing up and saw a shadow moving slowly to the door. In the next moment, the light was switched on. The kitchen and living room suddenly became flooded with light, and I flinched and instinctively shut my eyes tight.

“What’s going on?”

The voice I heard in the distance seemed to be trembling, and I looked up and peered through my eyelids. Because my eyes had been closed for

so long, my vision was muddled and it took a while to form a clear image. My husband was staring at me.

“What is that?”

I followed my husband’s gaze and looked down.

My body, soaked in rain, was covered in white. From my arms and chest, stomach and thighs, to calves and ankles, countless white things covered my body like fish scales. They were wisteria petals. The petals, still tinged with color, were soft and moist and looked as if they had just left the branch. They clung to my body, still alive. They even fell even on my neck and shoulders.

“What the hell happened?”

I looked straight into my husband’s face. So this is what the man looked like. Why didn’t I realize until now?

“Who are you?” my husband continued in a nervous voice that seemed to trail off.

“I don’t know,” I said. “All I know is that it has nothing to do with you.”

The raindrops pelted the outer walls and windows more intensely than before. The strong wind swayed the branches and rustled the leaves. Eventually, I noticed something else mixed in with the sounds. It was a sound so faint that if I didn’t listen carefully, it would be lost. But the sound pursued me. The sound came straight at me and sought me to listen. From the crevice of the rubble, from the fragments of broken glass, from the rifts of the demolished tree, from the unearthed dirt—from within myself.