I’m always interested in debates, serious or otherwise, on the difference between “gay” and “queer” spaces. Is it the lighting that’s different, or the outfits, or the books people value? Whatever it is, my social cravings typically extend beyond what most male-centric gay spots provide. A party where everyone looks more or less the same isn’t much of a party at all.

The place I most clearly identify as queer in its sensibility and politic is Jacob Riis Beach in New York City. People of every age, race, gender, and body type make their way to the haven of Bay 1, right in front of the abandoned Neponsit Beach Hospital. The four-story edifice, with its busted windows and barbed-wire fencing, walls off bathers from the nearby suburbs. It’s the shoddy backdrop of a glorious scene.

On a busy day, the cacophony of portable speakers sets the mood as you venture onto the sand to find friends — there’s disco, house, eighties pop, nineties pop, hyperpop, merengue, reggaeton, R&B, rap. Here, you’re immediately and materially connected to those around you — you’re also forced to look up and around because of the patchy cell reception. If you do find a signal, congratulations! If not, you’re in good company. The opportunity to unplug and connect with strangers is part of the appeal of Riis. Though once, in a rare blip of service, I received a long text message from a close friend saying my recent actions had hurt them, so I spent the next thirty minutes drafting a lengthy, apologetic response. It was split into three text blocks, and naturally, the texts delivered out of order when I tried to send them. Jumbling heartfelt correspondence feels right for Riis. At least we could joke about it later; this friend and I had spent plenty of time out here together. They understood.

We don’t have to queer everything, but Riis seems like the ideal site to queer effective communication. Maybe my apology’s breakage made it truer and more vulnerable. Likewise, a logical, linear format seems, to me, an insufficient mode for capturing the grand unruliness that is Riis.

If these paragraphs seem out of order, they might be.

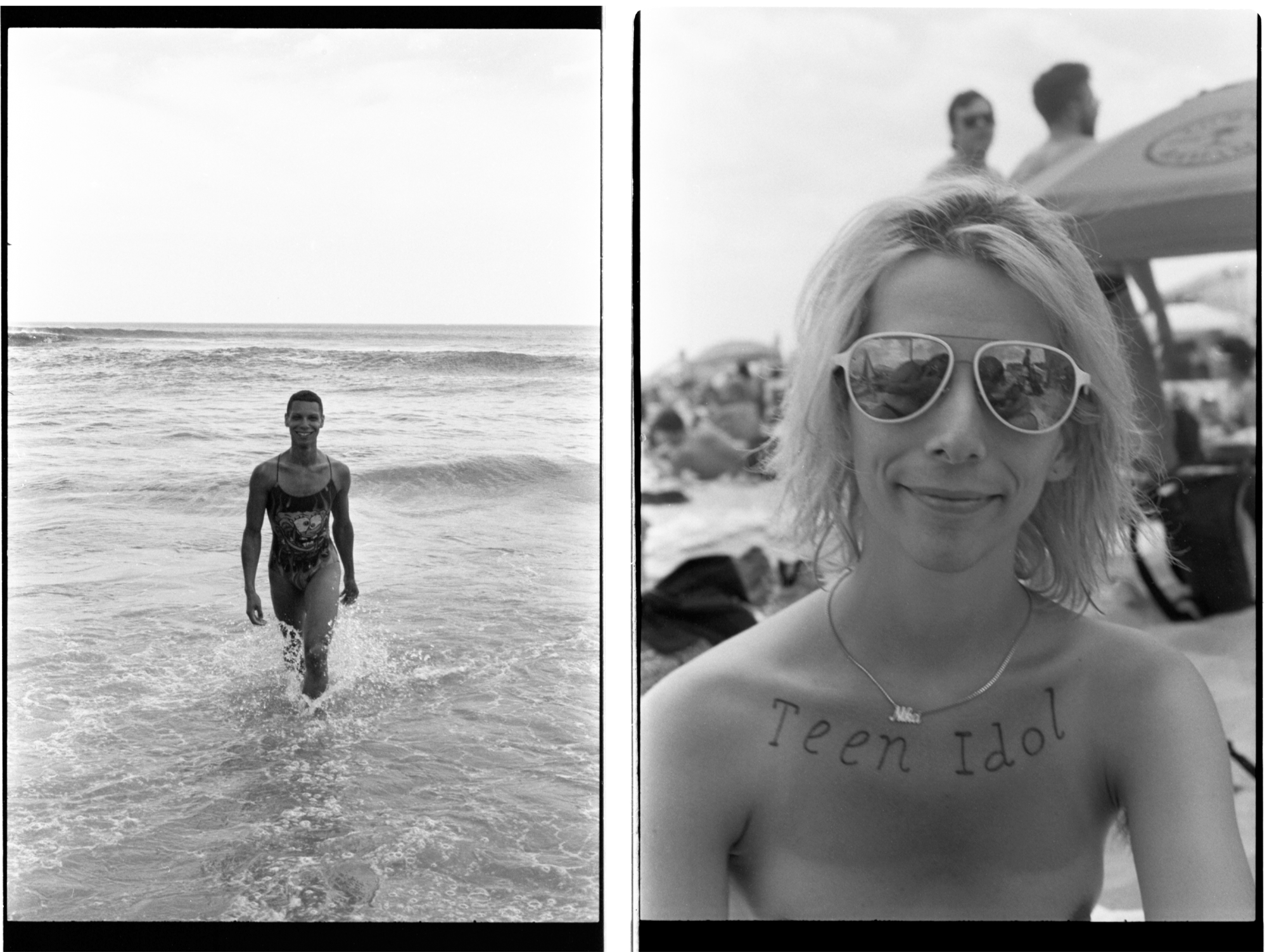

I was a twenty-one-year-old college student when I first visited Riis, following friends I met out in Brooklyn while home in New Jersey for the summer. Barely out of baby gay range, I was excited to see it for myself after hearing the hype. My swimsuit, patterned with shells and seahorses, hit my leg mid-thigh — defiantly shorter than the board shorts I’d seen on most men, sometimes, inexplicably, with underwear below. Arriving at Riis, though, I quickly learned there were more options than I’d ever considered: g-string bikinis, super high-cut swim briefs, jock straps, or nothing at all. Many swam with their breasts out, enjoying the legal toplessness that New York has had on the books since ’92 (a right challenged by antagonistic, less body-positive attitudes around the city and state). Proximity to other people who were free made it seem more possible for me to free myself.

There has, of course, also been resistance to this utopian beach fashion. In A Restricted Country, Joan Nestle writes that in the sixties police would “clean up the beach” by taking men whose suits were too showy into custody. This exact issue played a pivotal role in Harvey Milk’s relationship with Craig Rodwell, whom he dated after his longest romance, Joe Campbell (both of whom he met at Riis). Rodwell, a member of the Mattachine Society, was once arrested and detained for three days after fighting with officers who were harassing gay men in risqué bikinis. The police shaved his head in jail, and once Milk saw him again, he seemed horrified more so by the state of his lover’s hair than by the actions of the state. He faulted Rodwell for getting into trouble and found his radicalism “naïve and silly,” Lillian Faderman writes in Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death, which “triggered the beginning of the end of the relationship.” Riis is for everyone, but it is especially, I think, for people like Rodwell.

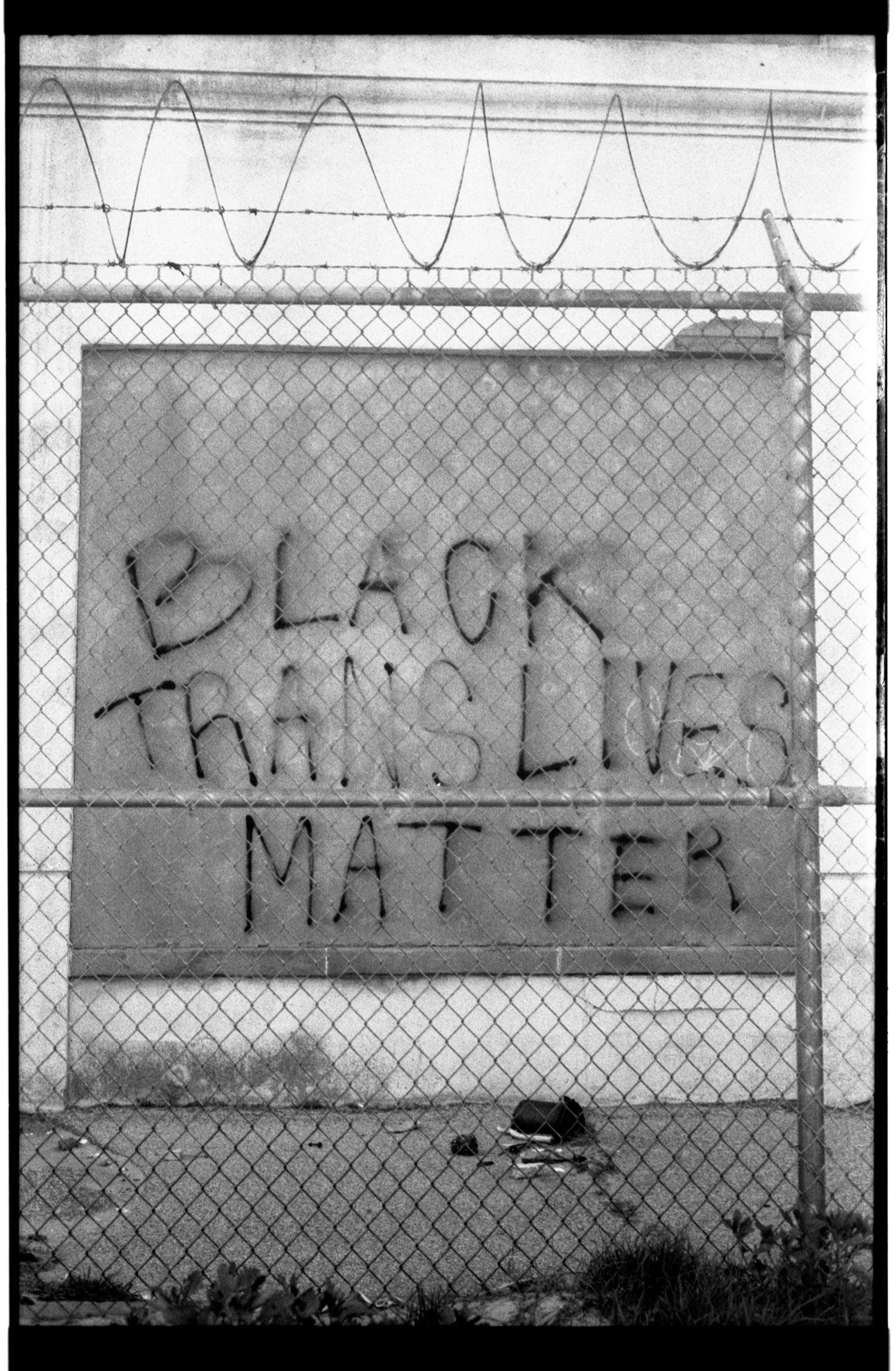

I once witnessed an altercation between a group of sunbathing cops and surrounding beachgoers over a Blue Lives Matter flag the cops were flying. Out-reasoned and outnumbered, they took it down, and we never saw them fly it at Riis again. This was in the aftermath of — and empowered by — the 2020 rebellion in response to George Floyd’s murder, a moment most sharply chronicled by Tobi Haslett in his essay “Magic Actions,” named for an Amiri Baraka quote on acts of civil revolt. This city had just seen what collective action can accomplish and its residents were riding high on nerve. The flag removal was a magic action, an answer to the history of queer and trans people finding themselves policed at Riis.

In Gay New York, George Chauncey notes numerous arrests of men for cruising at Riis in the years following World War II. Nestle’s A Restricted Country details constant police surveillance of lesbian and gay Riis-goers twenty years post-WWII; neighbors did their part, with teenagers laughing and pointing from their bikes, while the most rabid spies even observed the debauchery through telescopes. Regardless, Riis queers persisted — writer and scholar Jack Parlett notes Riis earned the nickname “Screech Beach” among gays in the sixties. Walking through the water — nasty, at times, seaweed-filled and seasoned with plastic wrappers — I feel beautiful, knowing that a historic project of survival holds me in its cold.

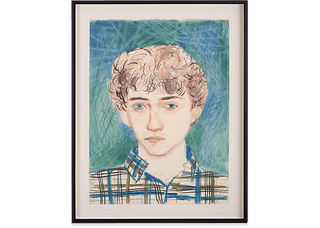

Andersson Lopez and Nika Lomazzo

In his new history, Fire Island, Parlett identifies Frank O’Hara as an admirer of Riis, noting that O’Hara tried tempting John Ashbery back from Paris by conjuring the pleasures of the beach in a letter. Audre Lorde also writes about trips to Riis in Zami, a New Spelling of My Name.

If this sounds like a name-dropping exercise, that’s because it is: Riis’s ties to queer literary history — and queer history at large — astound me. Though of course not all of these celebrated writers were known figures at the time, at Riis today, surrounded by all kinds of artists, I sometimes get the feeling of being in a kind of incubator or creative retreat. You never know who you might spot at a queer venue, Riis or otherwise. I consider this experience equalizing, and it should perhaps model what true access can look like for increasingly money-hungry queer events and spaces. The places that are for us, in a global sense, are limited, but the distance between us all is blissfully narrowed as a result. What if more of us chose equity over profit and clout, and worked harder to break down the partitions between queer factions?

Socioeconomic accessibility has always been central to Riis: in We Too, Must Love, published in 1958, Ann Aldrich describes Riis as the affordable alternative for New York gays unable to vacation on Fire Island or the Hamptons. It’s also known as “The People’s Beach.”

Kyle Carrero Lopez, Basit Shittu, and Garrett Allen.

Anyone who’s traveled to Riis by train from upper Brooklyn or higher can attest to the tedium of the transfer-heavy journey, but my favorite mode of public transit is the ferry to Rockaway. I went out one night a few years ago with the artist Asafe Pereira, whose photographs appear throughout this essay, and we ended up at a friend’s apartment around 4 A.M. with a pair of girls we’d just met, all five of us chatty, wired, and not working the next day. When someone eventually suggested we go to Riis, it didn’t take long for us to get to Pier 11 and catch the 6:15 (the first of the day). The morning sun and views of Manhattan and Coney Island greeted us along the journey to our destination, where we set up blankets and sheets and napped in near solitude.

Only a couple of scattered groups had arrived when we awoke a couple of hours later. No one had bothered us. We were in heaven, the hovering seagulls above as our beaked seraphim. It felt the way it always did at Riis: like this public good was truly ours, free from the impositions of any authority.

We laughed about it, remember?

On Riis Beach, in what used to be autumn,

the air’s odd warmth on our hands

as we sipped nutcrackers and danced.

The sand burned from the sun’s stare.

Days before we’d talked about meteorologists

dubbing our city subtropical, how dogwoods

and magnolias and other humid daughters

have found new life in the Big Apple.

Hours at the gay beach stretch like taffy.

You changed through black and pink swim thongs

and our speaker’s Donna sparred their Madonna

and somewhere in there we laughed about it again

how we had on hikes or bikes or stoned in parks,

sunned chests’ sweat like the pulp of a fresh gash.

It wasn’t a guffaw. You didn’t toss your head back.

There was a wind chime in your laugh. Glassy.

And haunted, surrendered to forces upon it.

Sanyu Kyeyune

At the time I’m writing this, the scheduled demolition of Neponsit Beach Hospital, our weathered shield, draws nearer and nearer. Speculations on what might replace the hospital vary from playground (worst-case) to community-centered wellness facility (best-case), and the sanctity of Riis remains very much at risk. I back every effort to preserve this place that has changed and even saved my life and the lives of so many. Though I wonder sometimes if this rescue mission might be side-stepping the issue that we will one day lose Riis anyway; that we are already losing Riis. Things look a little different with each passing year. Sand dunes disappear, shorelines shift, the beach shrinks. What actually can be saved, I think, is the spirit of Riis. There were Riises before Riis, and they’re long gone now, and they were what they were because of the people, not the locale. To begin claiming new public space for queer and trans people, all we need to do is go there together. Demolition is part of any builders’ process.

One day at Riis, I finally made it out to an elusive sandbar fifty or so feet out from the shore. It’d been folkloric, to me, having heard of its appearance on days I hadn’t visited. From that distance, the beach umbrellas looked like mushrooms lined up: an arc of a fairy ring. The people dancing around them were about the same size.