I have long been fascinated by the mechanisms of oblivion. Who do we remember? Who do we still mourn decades or even centuries later? Why are so many forgotten? We are fortunately witnessing a revolution in the ways in which our histories are written — we know that if we want people to believe and participate in the concept of history, it needs to reflect more than just the ruling class. In this context it isn’t a surprise that the American portrait artist Larry Stanton, who died from AIDS in 1984, is now finally being celebrated.

Yet it all started by chance, or so my friend Fabio Cherstich told me when I asked him how he had discovered an artist who sold a mere seven works during his lifetime, remaining unacknowledged by major museums and cultural institutions. Cherstich, an Italian theater director and visual art aficionado, was researching the painter Patrick Angus when he found the few images of Stanton’s work that were available online. Unable to resist the palpable charm in Stanton’s art — which had previously mesmerized the likes of David Hockney and Henry Geldzahler — Cherstich knew he had to find out more about him. He eventually got in touch with Arthur Lambert, Stanton’s partner, mentor, adoptive father, and the representative of his estate. This was in 2018 — Lambert, then in his eighties, immediately welcomed the much younger Cherstich into his home and into his world, showing him Stanton’s paintings and drawings that he kept at his flat. For the next few years, the two men would meet whenever Cherstich visited New York. They talked and wrote to each other, in the process of which Cherstich became more and more familiar with the world that Stanton had captured. He fell in love with both the art and the artist’s world.

Stanton was born into a white American middle-class family in the forties. He would struggle with alcoholism and severe mental health issues — following the death of his mother he was hospitalized twice. But he was also a lover and a fighter, a gay man in the seventies and early eighties who enjoyed the liberation that came with those years in places such as Fire Island and LA. And to live, like so many of us, he told stories. Whenever he could, he drew the men he met, most of them young and searching like himself. Since Stanton was not interested in abstract art, he became a chronicler of the times he lived in and created a kind of involuntary memorial because many of his models died from AIDS just like he would. Many of the faces we can see in his works belong to a whole generation lost to an (ongoing) pandemic that — especially considering the scale of its devastation with an estimate of 36.3 million lives lost — still does not receive enough attention. In the face of such apathy, it’s the task of the next generation to name, mourn, and ultimately celebrate these lives that have been cut short. There is still so much pain left unspoken and so many lives to be discovered. So much history that is yet incomplete. This is the reparative project that Lambert and Cherstich are engaged in, ensuring that Stanton’s art and the story of his life and contemporaries are passed down.

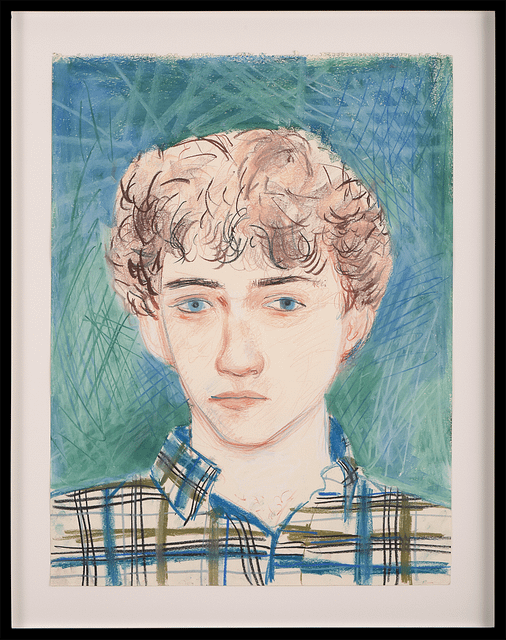

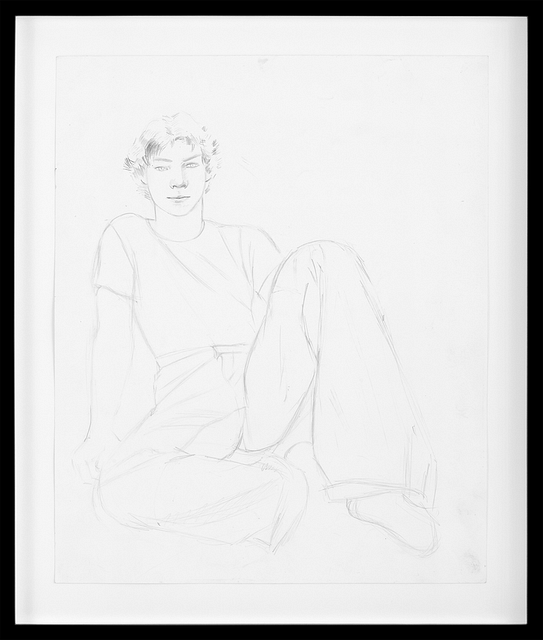

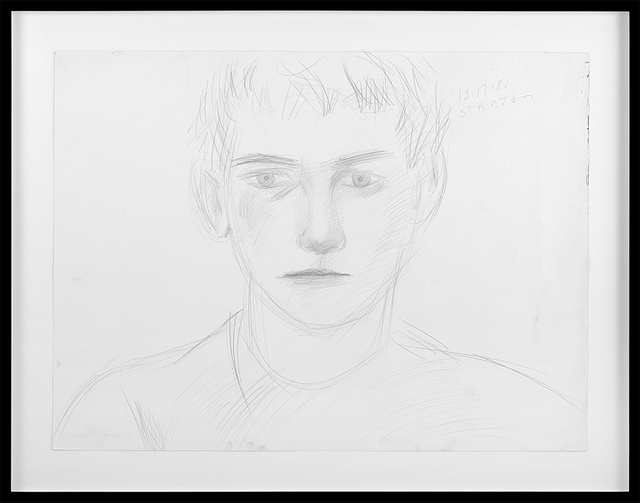

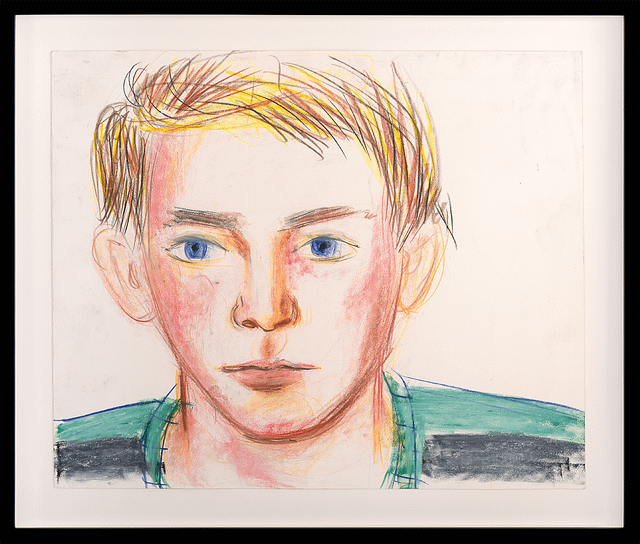

What do we see when we look at Stanton’s art in more detail? Lambert and Cherstich generously compiled a monograph entitled Larry Stanton: Think of Me When It Thunders, released by Apartamento earlier this year, allowing us to pore over a selection of Stanton’s works in one volume. (There is only one other monograph, assembled by Hockney and Geldzahler and published by Twelvetrees Press in 1986.) We see photos and polaroids of Stanton, his friends, and sometimes his models, some of whom Lambert was able to identify, while others remained anonymous as Stanton painted them during spontaneous live sittings. These are the portraits of men Stanton met during his nights out, who agreed to pose for him and whose faces Stanton portrayed with an extraordinary intensity. We can still feel that these were live portraits, that Stanton needed to have these strangers in front of him to paint them. We can also still feel the nocturnal atmosphere in which they met, the moment after intoxication, the fine line many of these subjects treaded — caught between the imminent danger they all faced and being young and free. There is an unmistakable urge to capture this world in these portraits, and there is a melancholia in the boys’ faces that isn’t just imposed through our hindsight.

And then there were the people Stanton could render from memory. His good friend Alice Sulit; his crazy Maine Coon cat, Sidney; his therapist, Dr. Mayo; his family; and of course Lambert himself. In these portraits we see a world that was relatively small, Stanton didn’t leave Manhattan very often and following his more severe mental episodes he was entirely devoted to his art and the love those people evidently felt for him. In his later works we see an artist coming into his own, and it feels far too soon when we arrive at those final pieces. The drawings he made during his last weeks in hospital. Where he was dying from AIDS. Where Lambert had no say over his care as the hospital didn’t recognize him as family. Where Stanton ultimately died alone. These final works show an artist’s incredulity at his own death. The knowledge that he still had so much living to do.

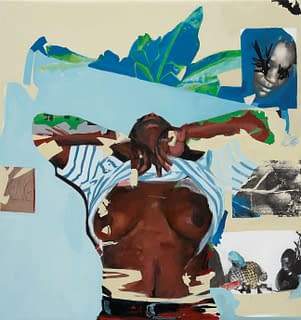

Earlier this month another commemoration of Stanton came to fruition: On July 5, an exhibition entitled The Male Gaze: From Larry Stanton to Now launched at The Artist Room in London. Milo Astaire, who only opened the gallery last year, contacted Cherstich after seeing some of Stanton’s works on Instagram and together they developed the idea of a group show. (Following exhibitions at the Apalazzo Gallery in Brescia and Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York, this is the first time that Stanton’s work is on show in the UK.) Stanton’s portraits and self-portraits can be seen alongside works by Kenneth Bergfeld, Jimmy DeSana, Cary Kwok, Paul P., Leon Pozniakow, and David Weishaar — all of them exploring what happens when men look at men. There was a real buzz at the opening despite the strangely humid London heat. The gallery is on the third floor of a Soho building, and it was moving to see a new generation of young men looking at Stanton’s works. Many of whom he would undoubtedly have loved to paint, members of London’s queer community, which has always been here in some form and is as old as the city itself. I was struck once again by art’s ability to survive, to still be there when everything else is gone. To bear testament to those who have come before us. It was uplifting to realize that sometimes it’s beauty that stands at the end of our otherwise so difficult lives. As a writer, I don’t often go to exhibition openings, but I could recognize that moment of joy of a thing finally coming together. The opening was also a moment of resistance. Dr. Mayo, Stanton’s friend and therapist, was right when she said to him during his final weeks: “nothing dies that is remembered.” A story that continues to be told is a powerful thing.