“Become old, young one.” In West Asia, it is common to hear old women say these words to strangers. The phrase may be a prayer, and it could just as easily be a curse. It all depends on how you treat your elders, the past, your future.

Jala Wahid is a multidisciplinary artist committed to exploring what it means to belong to, to remember, to care for, to carry, to be (from) Southern Kurdistan.

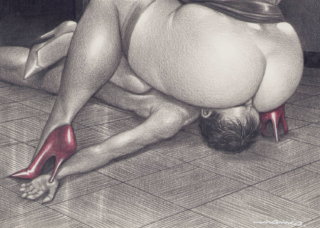

Facing Peril Years Deeper Love, 2021 Courtesy of the artists and Sophie Tappeiner, Vienna. Photo credit: Kunst-Dokumentation.com

Anger and Euphoria (2019) consists of two bodies that stand tall in their brokenness. Nearly life-size, the colorful statues are missing their upper halves. At first glance, they are echoes of monuments — they carry the trace of destruction, the haunting presence of what can no longer be named. But these are also dancing bodies; sweat drips down, the feeling of wind on the skin. Wahid plays with our senses. And she populates her work with whispers that know Kurdish.

Kurd as in identity, culture, heritage, and history. Kurd as in the paradox of diaspora — a people, their land, and the continued oppression refusing their right to nationhood.

Kurdish as in a language under attack — children banned from learning to read or write their mother tongue. Kurdish as in a language that survives — carried from one body to the next, one generation after another. Kurdish as in creating songs to preserve poetry. An old wish; sing, may your body become the archive.

Let us speak with one tongue, let our hearts beat as one heart and let us be members of one invisible body, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Niru Ratnam Gallery, London. Photo credit: Damian Griffiths

In Let Us Speak with One Tongue, Let Our Hearts Beat as One Heart and Let Us Be Members of One Invisible Body (2021), a large brown backdrop resembling a flag, a map, a landscape is punctured, torn, and held together by bodies, faces, and pointed fingers. On the left side is a cutout of a star — a motif of Kurdish fighters. On the right is a mouth, larger than life and bravely open: breathing, speaking, taking space, singing. Jala Wahid’s installation is defiantly adorned by femininity. Brightly colored and jeweled, they flirt with lipsticks, nail polish — dare one say, with pleasure.

Filth as in hyphenates can’t carry such multiplicities. Filth as in the pressure to make sense in English. Filth as in the violence of the dominant language. The erasure disrupted even the silence; it aimed to capture the stories that allowed for survival. Filth as in flight.

Jala Wahid is a British Kurd artist who claims space for a people who know the languages of silence. Wahid refuses to simplify history or geography. Instead, she brings the viewer into a space where we find all that we have known and all that we will never fully understand. Her practice has long, deep roots that are BIPOC and feminist. Her commitment to her marginalized language evokes Gloria Anzaldúa and her borderlands. The conviction and seduction of her sculpted bodies has the spirit of Audre Lorde’s anger and erotics. Her relationship to storytelling embodies Trinh T. Minh-ha’s reclamation of “grandma’s story” — as history itself — and its power to destroy and to heal.

Evil Eye (Moonlight), 2020. Courtesy of the artists and Sophie Tappeiner, Vienna.

In Evil Eye (Moonlight) (2020), Wahid presents us with a massive eye, colored by the many shades of the sky, looking away from the viewer. “It has to be an understanding of the precariousness of the Other. This is what makes the face belong to the sphere of ethics,” writes Judith Butler in Precarious Life. In Wahid’s forms, the personhood is neither that of the colonizers nor the patriarchs.

You who are reading in English, move carefully. Here — woven in the silent spaces in between — are traces of being Othered. Wahid’s work is as urgent as lived experience and as intergenerational as survival itself.

This “I” does not predate “you.”

Meet Wahid’s Southern Kurdistan.