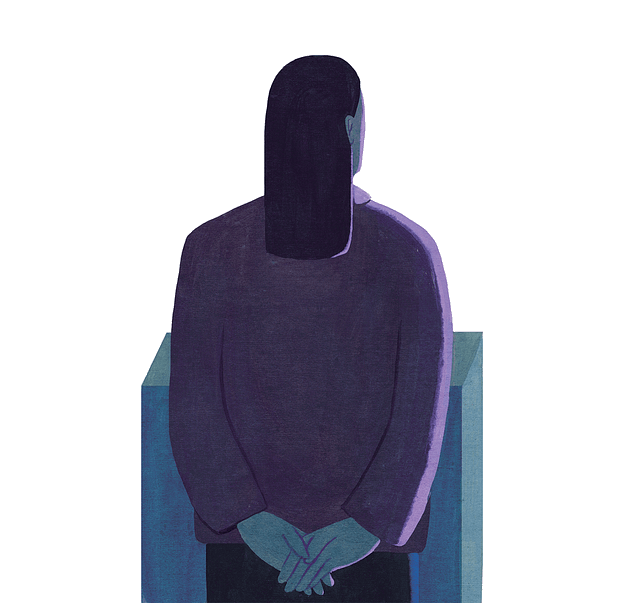

Throughout her morning briefing, the chancellor broods over an unusual prohibition. No one has come right out and said anything, but having worked this many years as a solicitor, she knows an injunction when she sees one. Her awareness arrived at dawn the previous day when, while praying, she realized she hadn’t had a bowel movement in eight days. Eight days! She was embarrassed by her own body. She had been preoccupied with her trip, yes, but even so, eight days is a long time to go without noticing something so essential. Excretion being incontrovertible proof of life, she rose from the prayer rug and placed her left thumb at the base of its twin to check for a pulse. She held her breath and in that dilated hush conflated the clock’s ticking for the high-stepping one-two of her heart. Faint but present, she decided. This was nothing more than a once-in-a-lifetime constipation. It was quite impressive, really. She let out a cracked laugh and made bergamot tea to inspire her insides to move.

Her insides did not move.

Dread, as it is contractually obligated to do, arrived at twilight. The chancellor shed her bedsheets, taking sandaled steps to the doctor’s empty quarters. Years ago, the doctor had worked and lived in the capitol building, but the chancellor ended that tradition early in her administration, thinking it best for the doctor and his wife to have some privacy. In that spirit, after unlocking the door, she ventured only far enough into the office to retrieve the stethoscope from its peg, which, in the dim light of the hallway, cast a shadow that reminded her of shoelaces on a telephone wire, which reminded her of the West, and her son.

Back in her bedroom, she moved the bitingly cold disc up and down her chest. When all the receiver reported was a booming silence, she pressed it directly against her nipples and then her stomach, hoping to hear the gurgling of a digestive tract. She heard nothing and began to pace, eventually stopping to study her reflections in the triptych mirrors of her wardrobe. Standing there, she attempted to coax her infamous blue vein to throb up the right side of her skull, a fleshy parlor trick she once used to entertain her late husband. It was so prominent a feature that a political cartoonist, having illustrated the chancellor’s head as a simulacrum of the earth (a play on her ego), rendered the vein as the Nile River. Her three reflections strained, she pushed her fingernails into her palms, but the vein stayed mulishly flat, dry. Her eyes refocused on her naked and quiet body. Understanding unspooled slowly — if she was alive, it was on something of a technicality. When she slept, she dreamed of her mother brushing her hair with steel wool. She did not presume to take that errant scene as a flare from her subconscious; she liked psychoanalysts well enough, and the writers who thought themselves psychoanalysts, but dreams are often no more interpretable than raw electricity.

Following the morning briefing, the chancellor attends to her obligations as a token of herself. She nods at whatever her aides say, clumsily deflecting questions about the trip she had taken to see her son. She is too absorbed to pay attention, too busy extracting what she can from every story of immortality, of extra life, that she can remember. Myths and parables about athanasia, everlasting existence invariably turning into torment. It isn’t until her last meeting, after she is reminded about an upcoming lunch with a potential biographer, that she knows she must balance a simpler counterfeit equation.

How ironic, or if not ironic then symmetrical, for her to be tethered to her original act of artifice.

It hadn’t been a year since her husband passed when she and her two brothers had gathered around her dining table to drink wine. They made clichéd jokes about their state, about how one could never underestimate its citizens, how these fools, much like children, could be conned into voting for a modern-day Houdini.

“You should be our Houdini!” her eldest brother said to her. She laughed, saying, “Ah, don’t forget, a young widow would get sympathy votes, too.”

“You’re not that young,” he teased. “No, it’s not that. You’ve always been a little, um — ”

Her middle brother finished the sentence: “Joyless.”

“Yes, that’s it exactly! Joyless. It’s easy to vote for someone who can’t possibly be in it for themselves. There’s no chance of corruption. Plus, you’re a solicitor.”

They hadn’t meant any offense, nor did she take any. They were engineers and spoke plainly. Yet that sentence, no, the word, joyless, clarified her life in retrospect. Joyless. They were right, and she knew she had always been this way. It’s not that she couldn’t experience happiness, but it was a wave without froth. Her joylessness had a smell to it, too; people understood that nothing could compel in her the admixture of illogic and ecstasy that gave all life its necessary gratuity. Those closest to her took this deficiency personally. It was why her husband’s expectant smile waned as he aged, and it was perhaps why her son left to spend the summer abroad with his paternal uncle and hadn’t returned — not for twenty years. “You’re right, you know. I should be our Houdini.” She was serious and spent the rest of that evening persuading her two brothers to help with her plan, which formed and re-formed as they spoke.

Six months later, she stood unsmiling in the town square in front of a box of flyers announcing her candidacy for council. To her right was a rusted lorry that her inventive brothers had lined with aluminum, under which they had buried an intricately improvised electromagnet. When a sizable crowd semicircled her and urged her to speak, to say what she had to say, she raised her arms, no different from how a waiter might lift a tray of plates, and the rusted lorry started to creak. Within seconds, the lorry had levitated, stopping, as by her brothers’ design, with enough space for her to occupy its shadow. For ten minutes, she remained below the suspended lorry, refusing to say a single word. Meanwhile, the crowd had tripled in size and was now begging for any kind of declaration. Finally, her watch chirruped, and she stepped out from underneath the lorry and went home. As she opened the door to her flat, the vehicle crashed to the ground, sending the remaining flyers into the clangorous wind. On election day, she won the council’s first chair.

She wouldn’t need the benefit of duplicity again, as she would turn out to be a talented legislator. In her mind, all one needed to be effective in a position such as hers was observation and anticipation. Cultivating those skills (they were skills, not gifts), she would come to enjoy almost universal approval from citizens and fellow officials alike. When she ran for chancellor, a campaign that would have been considered inevitable if she were a man, people thought she was glibly chastising the state for its gender bias. Her opponent, a man who had held the post for as many years as she had held hers on the council, shared the public’s assumptions and didn’t bother campaigning against her. What’s more, he secretly admired his challenger for reasons he couldn’t quite elucidate. “A certain… levelheadedness… ” was the best he could do. Then, four days before the election, he suffered a pulmonary embolism while eating a bowl of stewed gourds. As news of his death spread, there were those who remembered the councilwoman’s trick with the truck. The press, which in states as small as theirs often operated as a singular consciousness, considered that she had had something to do with the chancellor’s untimely demise, perhaps even her late husband’s. Her brothers were worried they would write about their suspicions. She knew they would do no such thing. Like the deceased chancellor, the press was roughly aware of her true gift, her low-ceilinged sentiments, and how that gift might serve them.

She proved more than worthy of the people’s trust. Though she had a general distaste for her constituents — she thought most of them regressive and stupid — she was able to make their needs paramount. She navigated a secession from the larger republic with shrewd grace, arranging for a beneficial trade agreement on their leading export (the fateful gourds), and coordinated the construction of two lucrative transit hubs. Near the end of her first term, her brothers burst into her office with an announcement. “The deadline has passed.”

“What deadline?”

“To register candidates. You’re running unopposed.”

She nodded, satisfied. Even the press didn’t have anything negative to say, save for an occasional half-hearted slight about her growing self-regard. Three terms later, when she was constitutionally obligated to abdicate her office, the council suggested amending said constitution (a pathetic screed, in her opinion), with a onetime provision that allowed her to hold the position until death. She agreed, shrugging. “I had no other plans for my time.” She went on with her duties, content that she would be occupied. She held her position for more years than her late husband had lived. Both of her brothers passed away during her administration. She didn’t bother grieving them, knowing they wouldn’t want her to lie in such a manner. In more recent years, she achieved near-celebrity status in the West; a newspaper of some standing called her the world’s first and only benevolent dictator. Two weeks following the article’s publication, when she was invited to speak at a university where her son was a tenured professor, she made the travel arrangements herself.

After the chancellor’s speech at the university, there was a corporate-sponsored question and answer session with an attractive media personality she had once seen on television. The young man asked her banal questions, allowing her to answer while she scanned the crowd for her son, who had invited her to his house for dinner after the event. She found her son in the third row. He had a long forehead and seemed interested in what she might have to say. “Do you think,” the media personality said, “that being a woman, being a mother, has helped you govern so effectively?” The more she thought about his question, the angrier she became. She wanted to ask him if the pomade had assumed control of his hippocampus, but she instead met her son’s gaze. “No, not at all.”

Her son’s home was inherited from one of her brothers, who never had any children of his own. Her son decorated tastefully, updating what was necessary, leaving the signifiers that might remind guests of a rich past. He had a picture of her on the kitchen wall. Small but there. How many times had they talked over the years? A dozen? Neither of them made much effort. As it began to rain, they dined on a roast chicken. Her son was clever and a professor of history, no less. The night warm and waning, she said, “They love me here, it seems.” He thought for a moment before replying. “They love you as they have loved me.” He left no doubt as to his meaning: they love you because your insanity is the obverse of theirs, like mine. She understood then that her gift, her joylessness, wasn’t what drove her son away. He had simply inherited her gift and made decisions as she would have. The West was the correct choice for him, that was all. She instantly regretted orchestrating this reunion, but how else could she have known who he was and who they were in relation to each other?

The drive to the airport cut through a wedge of forest, and due to the rain, the road had become untrustworthy with mud, grimy. A heavy fog swallowed their headlights, converting the beams to yellow smoke. The chancellor’s son took a wrong turn and then two more before stopping the car to gather himself. He looked over at her, but she would not look at him, as she was offended by his miscalculations. In the still dark, the trees seemed to gather closer to her window; she sensed their desire to breach the glass and shove their rain-slicked fingers down her throat. “Ah, I know where I went wrong,” her son said suddenly. He put the car in drive, returning them to the correct route.

Before parting ways, mother and son shook hands as warmly as they could.

Today, as she is reminded by her staff about the biographer, she understands that although her title is chancellor, she is a despot. Even if she is, as they say, benevolent, and no one in her state would think of ousting her, certain actions are immutably corrupt and must be reconciled. She should risk her life. No, one can risk only what they value. Perhaps she should arrange to stand in the town square again and this time allow herself to be crushed under metal. Yes, that’s it. She’ll make a posthumous announcement, too, a prerecorded speech about the lie that started her career. Yes. Tarnish the legacy. Yes. Punch her ego through with sunlight. Just as she comes to this conclusion, her brow begins to bead with milky sweat. Heat travels like a clattering train through her torso. She groans loudly and is struck, disgusted by the putrid smell of herself, the smell of a hot open gutter. “What’s wrong?” someone in the room asks.

The despot stands slowly, careful not to unclench any muscles, as a warm and foul seepage moves down the backs of her thighs.