1

During the food justice talk at my new job I watch four crows chase a hawk with a limp mouse in its beak. In a display of dominance, the hawk lands on the window of a new condominium and thrashes the mouse against the floor-to-ceiling window a worker just cleaned from a propelled harness on strings.

In down coats we make small talk about birds. How they were dinosaurs, older than us.

The food here grows in imported soil on what used to be an old paint

factory on top of Ohlone land colonized into an orchard at the end of the old railroad line. The fruits were packed and sent east.

I can maneuver through a commute while a daydream simultaneously

departs from one real moment into multiple imaginary outcomes. Yet I stop at the red light. I watch the black cat stalking patiently in the corner lot.

There’s no world at night in a closed room to interrupt the images of memory, so I wake to the day my four-year-old self broke my arm jumping from the downstairs neighbor’s fence, testing my ability to fly.

The hospital technician said I’m a bad man for setting the arm and causing more pain, but I was relieved to see the arm again. It was either twisted behind my back or my mind wouldn’t allow me to see the disfigurement. Tonight, I remember every detail of his face as he said those words, or I remember the words repeated back to me over the years.

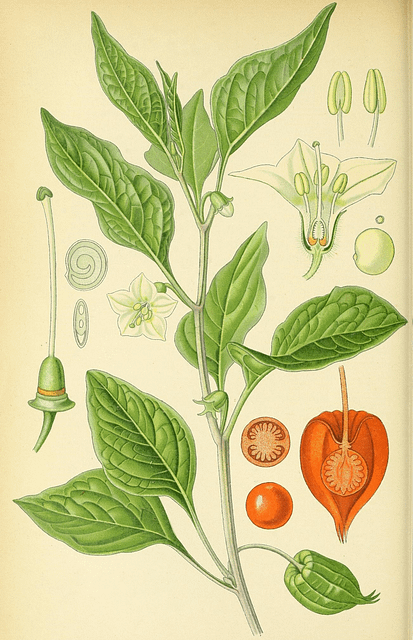

I refuse peripheral memories and trade them for worry for the short-term future. How to get along with the co-worker who flaunts minerals to prove his knowledge of soil. Gypsum. Potassium. Manganese. Invisible, they mean little to me.

2

The missionary inventoried my great-grandmother in rushed cursive as

Julia the Indian woman on February 9, 1897, in the mission home for Chinese women.

I refuse the colloquial colors of the bruises the missionary noted on her, but think of them anyway, approximations of black and blue. The archivist ruler of a color palette on the bottom of the scanned page annunciates what is missing from the document. Nearly everything.

The historian who wrote a book on San Francisco Chinatown noted my great-grandfather, before he was murdered, as a chef and gang member who, when commanded, sullenly harvested blooms from the streets out of

nowhere for the table display. He listed the petal colors, but misspelled violet violent.

I grow sore from scraping mustard and dandelion weeds from the rows and imagine how my mouth might water at the sight of them from pavement cracks in a hungry future.

I dream the fictional documentary filmmaker sat legs crossed on a stool and said it’s not enough for the artist to simply notice, and to do so is just a record of one’s leisure, which is not art.

Earlier I stood in the patch of grass at the traffic triangle before the sun rose and saw a shooting star. I surged to tell someone about it. For someone to witness me witness it.

You say you saw a barn owl on your bike ride along the lake at dusk with a mouse in its beak. The owl, in your words, did a 180-degree turn revealing its beauty in the streetlamp. I didn’t see it, but I can see it.

3

The farm, my uncle tells me, is a couple blocks from where my grandmother worked at a candy factory and lost her fingers. If I knew her, I know she would likely disapprove of my decision to work with my hands. My face more like her husband’s, the son of Julia, who tricked my grandmother, 20 years older than his photograph.

Outside the locked gate, a woman who doesn’t speak English points to an empty egg carton while I put artichoke seeds in lines down the potting soil. Our ritual. I collect only five eggs this time from the old hens. The woman and I say thank you to each other back and forth until it feels like a full conversation.

Today my thoughts bore me. The yellow of rain gear. The blue of blueprints. Must have been popularized by an excess in dye and then produced over and over out of nostalgia.

I want to feel my feet lifting from the weight of another seated on the other side of the past. I told you I might one day want a baby. You had a vasectomy you might reverse and come on my belly.

I put figure eight end caps on the irrigation lines, and I do this without thinking of anything.

I don’t dwell on loss, but move through life wanting more. I find this in my notes, but I’ve tried to write about my grandmother’s missing fingers for ten years and have memorized the words and never the feeling.

I curl the pea shoots around the twine. No. They curl, and I weaken them, retracing their way.