Book Review Online

Not Not Michel Houellebecq

On James Greer’s novel Bad Eminence.

By Digby Warde-Aldam

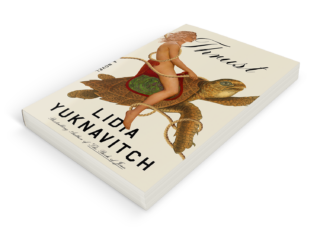

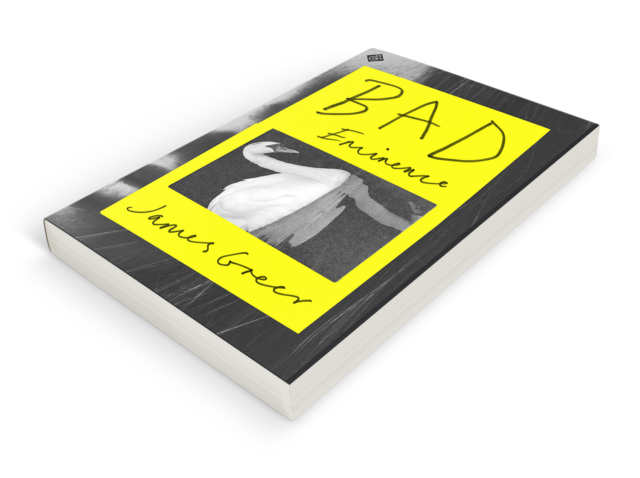

Bad Eminence

James Greer

And Other Stories, $26

A few pages into James Greer’s novel Bad Eminence, Vanessa, its literary translator protagonist, gives us a précis of her trade: “It boils down to this: you try to get down as best you can what the writer has written while also reproducing the way the writer wrote it — in a different language.”

Vanessa subsequently sums up two other tenets of the discipline: first, that “there’s no money in it” (good thing, then, that she is by her own admission “a privileged, entitled trust fund bitch,” the owner-occupier of a vast East Village apartment filled with Frank Gehry furniture and blue-chip art); second, that “nobody can agree what makes a good translation; nobody can agree what makes a bad translation; everybody agrees that it would be ideal if everyone could read the original work in the original language; everybody knows this is impossible.”

It helps, nevertheless, to have a decent grasp of the tongues you’re dealing with. Translation software might have come a long way since the early days of Babelfish, but the robots haven’t won yet. For anything longer than a basic phrase — “where did you buy those croissants?” — Google Translate, or any other contemporary platform will be incapable of penetrating the thickets of idiom and structural nuance that stand between any two given languages.

Not that this has prevented us from trying. Take the case of Pedro Carolino, a writer in nineteenth century Portugal who, for reasons lost to time, attempted to compile an up-to-date English phrasebook for “studious Portuguese and Brazilian Youth.” That he appears to have had no working knowledge of his target language and was thus incapable of beginning from scratch was of little consequence. He translated, word-for-word, an existing French phrasebook for Portuguese speakers. The result was English As She Is Spoke, published in 1855, a treasury of idiolect and the source of much anglophone mirth. The French croquer le marmot (“to knock on a door and wait”) became “to craunch the marmoset.” Better still, “after the paunch comes the dance,” which was presumably a rendering of the medieval aphorism “après la panse vient la danse,” denoting celebration or contentedness following a meal.

Unfortunately, the elegantly mangled phrases of English As She Is Spoke — one of the many texts alluded to in Bad Eminence — were never adopted by native speakers. Yet as Vanessa assures us, equally nonsensical howlers of historical translation have become everyday fixtures. As she tells it, phrases including “a fly in the ointment” and “a labor of love” have their origins in mistakes made by the Alexandria-based scholars who translated the Torah from Hebrew to Greek in the third century BCE.

If all this seems like so much digression, it’s worth noting that Bad Eminence is full of it. A good third of the novel consists of a string of tangents and red herrings, on subjects from the Lisbon earthquake of 1744; to American attitudes about coffee (they “have no idea how coffee is supposed to taste or how to make it or what it is,” apparently); to the seduction strategy of married Frenchmen (“a show of ersatz honesty, letting you know that they are vulnerable to hurt, that their heart has been broken; but life goes on, and you may as well let them fuck you in the ass they just blew smoke up because none but transitory pleasures remain”).

Snaking between these often-lengthy asides is a zany metafictional narrative full of high-wire turns of phrase and a virtuosically confusing employ of the double negative. When the twists and turns — and there are many, many twists and turns — get too knotted, proceedings pause for illustrated cocktail recipes based around Singani 63, Stephen Soderbergh’s designer spirit brand. (Vanessa drinks a lot of it; Greer himself has a writing credit on Soderbergh’s 2018 movie Unsane.)

The reader is addressed directly throughout, sometimes as a generic “you,” sometimes as the actress Juno Temple (a fellow tenant of Vanessa’s building who drops by for a drink; Juno, for the record, is another Soderbergh alumna and, weirdly enough, a high school classmate of mine). All this is recounted with a delivery that seems to have been xeroxed in from the pages of an Ottessa Moshfegh story, which given the intertextual density we’re dealing with, may well be intentional. It is not quite as clever as it thinks it is, but equally, not nearly as annoying as it sounds.

In brief, or bref, as Franco-British Vanessa, conversant in, inter alia, French, English, German, Italian, and Russian would no doubt say, this is the story of how our heroine was approached to translate the new novel by a writer described as “probably the most famous French novelist alive.” Her prospective client “writes like a clinically depressed teenager with a limited vocabulary and a taste for misapplied anglicisms and pop-culture references that are dated before his novels come out.”

Looking “like what death wanted you to think death looked like,” he is an alcoholic sleaze whose concession to healthy living is the occasional prepackaged pasta salad. He is prone to killing himself off — or at least, characters who share his name — in his own books and may or may not exist. Curiously, his name is Not Michel Houellebecq.

If this sounds quirky — and here I paraphrase Vanessa herself — it is about to get a whole lot quirkier: Not Michel Houellebecq is not in fact Not Michel Houellebecq (see what I mean about those double negatives?). Rather, Vanessa is led to believe, he is an actor hired by the true author of his novels, a publicity-shy novelist-slash-businessman with residences in New York, Paris, and Cap Ferret. His identity is not the only fictional ambiguity we’re dealing with: the new novel, it transpires, hasn’t even been written yet.

Regardless, this real Not Michel Houellebecq (or H2, as he is thankfully referred to for most of the novel) has somehow been reading the same, present-tense text as we have, in which Vanessa has some pages back expressed her belief “that a book should be translated before it’s been written.” Over a bewilderingly expensive sushi dinner accompanied by — what else? — Singani 63 cocktails, H2 proposes that Vanessa put her money where her mouth is. Or rather, his money — half a million dollars’ worth of it.

Out of professional vanity more than any financial motive, Vanessa accepts. But — you will be unsurprised to learn, however wearily by this point — all is not as it seems. First off, we lose the previously tight focus on translation, which is a shame, but only insofar as it’s a shame that, in the comic book albums of Hergé, we never really see Tintin “the boy reporter” doing much actual reporting.

What follows is a manic and highly enjoyable race back and forth between New York, Paris, and a smattering of French provinces. Several Singani 63 breaks later, it climaxes in an impressively stupid Alpine denouement with a duffel bag full of semiautomatic weapons and a Bond villain–esque mountain lair. And as with so many formally experimental but “accessible” novels that attempt to graft a tangible plot onto literary auto-commentary (hello, Martin Amis), whatever synthesis Greer arrives at uncouples spectacularly in its final chapters.

Patterns recur throughout: upturned triangle symbols may or may not point to the existence of a global conspiracy (prior to the events recounted, Vanessa is working on a translation of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Souvenirs du triangle d’or). Scarcely a character is introduced without at some point being paired with another — H1 and H2, Vanessa and her “bitch twin sister” Angelica, Juno and H2’s daughter Temple (who, early on, is found dead in a bathtub in the cul-de-sac of a plot dérivé), the aforementioned Robbe-Grillet novel and Anna Karenina, two hollowed-out copies of which Vanessa keeps in Paris and Manhattan, receptacles for a pharmacy’s worth of legal and illegal drugs.

Frankly, it’s exhausting. Yet even if you’re lost playing Bad Eminence’s Oulipo-bingo (and I have to confess, I was more than once), Vanessa and her apparently random plot detours might keep you reading. And even if they don’t, her observations will: decorating a bathroom “in black and white Métro tiles” is witheringly (and correctly) dismissed as “a fashionable thing to do in bourgeois circles in Metropolitan France”; a memorable passage on toilets aboard French high-speed trains is spot-on (clue: “they are not well-built”). A description of “a French bourgeois trying too hard to dress down” (no jacket, dress shirt tucked into ironed jeans) may be aimed at an easy target, but Greer nevertheless scores a perfect vingt sur vingt with it.

It’s a book you read for its parts, not their chaotic sum. Taken this way — and I write as someone who enjoys difficult Gallic literary exercises, Singani 63, and the kind of everyman detective fiction from which the novel takes its cue — Bad Eminence is immensely fun, and often very funny. How to pitch a book like this beyond my not-exactly-vast demographic, however, is anybody’s guess. As Pedro Carolino might have it, “you cannot to sell its. The actual-liking of the public is depraved they does not read who for to amuse one’s self and but to instruct one’s.” Indeed.

Finally, and purely incidentally, I should add that despite being published in French back in January, and a raft of other European languages shortly thereafter, Michel Houellebecq’s latest (and last?) novel will not appear in English until 2023. But for better or for worse, believe me: it does exist.