Book Review Online

Between Knowing and Not Knowing

On Ross Feld’s biography, Guston in Time.

By Ben Eastham

Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston

Ross Feld

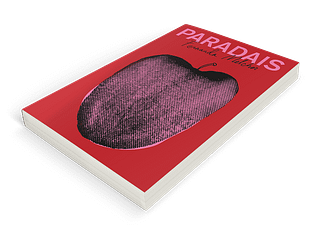

NYRB Classics, $18

“NOW,” is the first word in Ross Feld’s portrait of an artist in the world. It opens a letter written by Philip Guston in 1978, two years before a fatal heart attack, to the young poet who would, shortly before his own early death two decades later, use their correspondence as the basis for a book that hovers between criticism and biography, art and life. Guston is explaining that something has changed in the week since Feld last visited his studio. He has made a new painting, and this is important. “NOW,” he writes, “it is a different sort of contest — not what you saw — not what you — we — talked about. Now the contest is between knowing and not knowing.”

The painting in question is titled Mid-Day. Its central ground is occupied by a shambles of the artist’s favorite motifs — roughly shod shoes, irons, spiders, rusty nails, railroad spikes — rendered in Guston’s caricatural late style and signature abattoir-floor combination of cadmium red pigment, mars black, and titanium white. Over the stable horizontal of a clay brick wall loom the artist’s Cyclopean eye and the parted hair of his wife, Musa, who seems understandably reluctant to poke her head any further over the parapet. The whole heap of broken images is supported by a severed leg at its base, around the ankle of which is strapped what appears to be a silver watch. As is appropriate for a leg’s watch, it has no hands.

Both the “NOW” and the watch beg a question that runs through Feld’s portrait of a five-year friendship and the paintings produced in its span: what is the time of a work of art? Let’s consider a painting that laid the ground for Guston’s late work, completed a few years before they met. Combining comic-strip styling with the dreamlike mise-en-scène of metaphysical painting, The Studio depicts a cartoon Klansman hard at work in his atelier. With a brush held daintily in his red right hand, he is painting a self-portrait. A clock is on the wall. It has only one hand, which points up to a retracted stage curtain.

So: what’s the time of this painting? Is it the “NOW” of the year in which it was completed, and which diligent catalogers note in parentheses? Philip Guston, The Studio (1969). Or the “NOW” of our encounter with it: The Studio in the era of Black Lives Matter, or The Studio during the bombardment of Odessa? Perhaps it is the “NOW” of the artist’s imagination: The Studio as portrait of the Klansmen by whom Guston had been “haunted” since childhood, set in a space shaped by the inherited trauma of his parents’ decision to flee the pogroms in that same but different Odessa. The clock closely resembles the symbol of Mars: might we be in the elongated “NOW” of patriarchy and the violence that supports it? Or does the painting really exist in the eternal and unchanging “NOW” of Art with a capital A: The Studio as an arrangement of colors and forms that relies for its meaning on nothing beyond itself?

In the first of eight short chapters that move between anecdotes of a tender friendship and close readings of individual paintings, interpolated by letters from the artist, Feld puts forward his own proposal as to the ethos of Guston’s work. The painter and the poet are having lunch in the Village when Guston, whose insatiable appetite for food, cigarettes, and conversation contrasts with Feld’s restrained prose, sets off on a tangent about Walter Benjamin’s “notion of art as ruin.” It seems natural to Feld that an artist whose father had once peddled junk, and whose recent paintings are filled with the stuff, should be drawn to the idea. But he baulks when, during a public discussion a few days later, Guston suggests that Benjamin’s theory of allegory might be applied to his own paintings. A painter as sophisticated as Guston can’t be making allegories, objects Feld, it would be so gauche, so obvious, so unmodern. His objection is supported by another critic in the audience, and together they come up with more reasons the artist must be wrong. Guston takes it all in good humor: “Well,” he persists, “I still think I’m making allegories.”

This self-deprecating anecdote is set in 1976, shortly after Guston had written out of the blue to thank the twenty-something critic for an insightful review. If it marks the start of a friendship, it is a ruinous period in several other timelines relevant to Feld’s book and Guston’s paintings. Guston’s career was in tatters after a notorious show at Marlborough Gallery six years earlier, in which he abandoned the startlingly beautiful abstractions that established him as a leading figure of the New York School for a raft of bad-mannered, hooligan satires on American society. He had been made a pariah by the cognoscenti and had barely sold a work in the interim. The United States had been torn apart by Watergate, race riots, economic recession, and Vietnam. The standard bearers for New York’s status as the post-war capital of high modernist painting — Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko — were dead.

It is their legacy of a painterly abstraction that is absolutely pure, autonomous, and self-referential that Guston was accused of having betrayed. With typically elegant economy, Feld describes the rudely executed canvases that so offended his surviving peers: “Painting after painting,” he writes, “offers us plain things with the deadpan capacity to hold history: a hood, an overcoat, a bottle, a shoe, a pyramid, a bug, a wheel, a patched-up sphere, a teapot, a suitcase.” The phrase “painting after painting” serves two masters here: it conjures Guston’s prolific output at the time — canvas upon canvas piled up with the crapola of material life — even as it suggests that he was working after the death of painting itself. The structures supporting the myth of Abstract Expression (or, the United States) as the apotheosis of western culture have collapsed, and Guston is painting the ruins.

If the socially conscious paintings of Guston’s “early period” in the 1930s sought to change the world, and the melancholy abstractions of his “mature period” in the 1950s hinted at the possibility of transcending it, then his “late period” documents a disenchantment that might equally be enlightenment. In the bottom left of The Studio is a shape that might signify Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square. When it was first exhibited in 1915, the Ukrainian artist’s contribution was symbolically placed in the high corner of the room reserved for Orthodox icons. Here it has been relegated to the floor, where it stands beneath the glare of a single bare lightbulb. Painting has been deconsecrated and dethroned, brought back down from the heavens into the world of earth and blood. “My spirit,” writes Guston to Feld, “needs matter.”

The artist’s “return to figuration” is typically figured as having been catalyzed by a desire to comment on the parlous state of late-sixties American society: in a much-quoted interview, he speaks of his frustration at reading the news and then “going into [his] studio to adjust a red to a blue.” But Feld is right to suggest that the artist changed tack because he recognized intuitively that a decontaminated art risks becoming sterile. To illustrate the point, he takes some of the “plain things” that corrupted Guston’s paintings and considers the histories to which they might belong: the piles of abandoned shoes to victims of the death camps; the severed legs to the brother who died after losing his in a car accident; the lengths of rope to the father Philip found hanging from the rafters; the hoods to the persistence of white supremacy. Guston calls these intrusions of the world “impurities,” which by staining the work of art link it — like a spot of blood on a white shirt — to the world. (Feld identifies the whip hanging from the corner of Guston’s late masterpiece Green Rug with that suspended over the archetypal innocent in Piero’s Flagellation of Christ, in which a man with his back to the viewer watches the torture impassively. He wears white robes and a white turban that might, if you squint, be mistaken for a hood. In the moment after the painting is set, it will be flecked with blood.)

The pollution of a painting by the suffering that surrounds it continues long beyond its completion by the artist. The jacket of my review copy states that “it has been forgotten how scandalous and crude [Guston’s late] paintings … were initially deemed to be,” which seems like an odd claim when you consider the controversy around the postponement of a major retrospective in 2020 over the political sensitivity of the “hood paintings.” At issue here was, firstly, whether the paintings were contaminated by the recent proliferation of images online of police brutality against Black people and, secondly, whether a show which was years in gestation was adequately prepared for the shift. That the answer to the first question is manifestly yes is testament to the paintings’ continued relevance. Writing in the catalogue of Philip Guston Now (“NOW”?), Glenn Ligon argues that the “hood paintings” were “woke” precisely because they constituted a “betrayal of not just New York School abstraction but of the idea that living in a country built on white supremacy could leave one unmarked.” These portraits of artists as Klansmen angered the cultural establishment in 1970 by asking it to confront its implication in the brutalization of Black America instead of hiding art’s supposed autonomy. Half a century later, the same people got mad when it was suggested that Guston’s paintings might have been “marked” by the murder of George Floyd, and that museums might therefore need more time to adjust to the implications. The paintings are enduringly relevant because they are changed by the circumstances, not because they are insulated from them in the manner of a dead butterfly pinned to a corkboard inside an airless vitrine.

No survey of Abstract Expressionism could excite the same culture-war animus, for all that it was a CIA-supported tool of American imperialism marketed to domestic middlebrows and pinko Europeans as evidence of capitalism’s cultural superiority. Indeed, the formal purity of New York School abstraction has condemned even its greatest works to the fate of perfectly smooth commodities, free-floating signifiers ideally suited to serve as vehicles for the frictionless cultural and monetary transactions of globalized capitalism. Or, as Guston more mischievously puts it, “over-the-couch stuff” and “a decorator’s dream.” Whichever side you take, Feld is right to state that his friend’s rebuttal of abstraction “seems to raise the intellectual stakes higher than just one painter’s change of direction.”

In what might be a tribute to Guston’s superficially ramshackle but structurally complex late compositions, Feld builds his thesis on the relationship between art and the world out of the clutter of everyday life. We see Guston in his natural environment of home and cheap New York eateries: charming, articulate, mischievous, difficult but not exceptionally so, weak, garrulous, wholly dependent on his wife, generous, self-destructive, all too human. In representing the painter as of his time and place and yet enabled by his intellect and empathy to move tentatively beyond it, Feld dramatizes what Guston termed the “irritable mutual dependence of life and art — with their need and contempt for each other.” This reissue offers a timely reminder that art can no more be reduced to the life of its maker than it can be severed from it. From whatever period you take them, Guston’s paintings are neither universal forms that can be grasped intuitively in their entirety nor private mysteries knowable only by first generation Jewish American men in the middle of America’s century. They are examples of what art must always be: contests between knowing and not knowing, with one foot in and one foot out of the world.