Essay The Ecstasy issue

Wadden Sea Suite

By Dorthe Nors

Translated from the DANISH by CAROLINE WAIGHT

It’s dark in Huisduinen, south of Den Helder, in the Netherlands. I hear from Denmark that the first storm of autumn is drawing in from the North Sea, bringing winds of hurricane strength. It’s due to hit the northwest coast back home. I told my dad over the phone that I was going to the southernmost edge of the Wadden Sea, the vast, enigmatic tidal sea on the Dutch, German, and Danish coastlines, and he decided my timing was poor.

“But I’m about five hundred miles away from your storm,” I replied, because he’s often worried about people going about here and there. His West Jutlandic roots have a solid hold on him that way. Watching what you say and talking people back into place when they’re a tad too keen to move are normal in the West Jutlandic hinterland. The coast is for those lured by the foreign. They’ve no good soil, so they’re quite a sorry lot. But two miles farther in, we reach the hinterland. The hinterland is for those with money in real estate and profitable earth. They come down hard on wanderlust. Say you’re at some Christmas market in the hinterland with your gingerbread, and you’re making conversation at a stall that sells hand-knitted socks:

“So what are you up to these days?” the saleswoman asks you.

“I’m just back from London, actually,” you might say.

“London?! Oh, but that’s ghastly,” the saleswoman says. “And you do look a sorry little thing,” she might decide to add.

Big cities, free speech, and foreign lures are the work of the devil. All three are a threat to the existing order. The word bonde, Danish for farmer, comes from Norse, and means “settled man.” A settled man is master in his own house and reluctant to move.

What the women are, the dictionary of the Danish language neglects to mention. Still, one thing is for sure: a person glad to seek out other regions is a defector, an overløber, which comes from the German Überläufer, and describes a person who has gone over to the enemy. Any time you say you’ve been to New York, Berlin, or Cairo, what you’re really telling the hinterlander before you is that you don’t think he or she is good enough. My dad’s got this same conditioned reflex from his proud West Jutlandic forebears. One of the times he was most frustrated over my urge to see exotic places was when I moved to Fanø, in the Wadden Sea. Fanø is an island, and people who live in such places are encircled by water. That means wanderlust, no question, and anyway, water is dangerous. Ships go down. Ferries, too. My risk of drowning rose considerably, he felt.

But I lived on Fanø for a year. It was unforgettable. I was besotted with a married man. The married man was besotted with me being besotted with him, and it should have set all the lighthouses along the coast to flashing, but it didn’t. He lived far away, I lived in the village of Sønderho at the southern tip of the island, and with every day that passed I was swallowed up more and more by the landscape. The Wadden Sea is powerful, and I lived a far stretch out there. You don’t come out the other side unchanged.

First, I stayed at Julius Bomholt’s House, also called the Poet’s Home, a big old shipmaster’s house owned by Esbjerg Council. It is made available to Scandinavian writers as a retreat and was mine for six months. But when it came time to move out, I wasn’t done with Fanø. I had an extended trip to the U.S. coming up. The married man was involved. I thought I might as well stay in Sønderho until then, so I took a room with a lovable local woman in her shipmaster’s house. Johanne’s House, I call it in my memories, because that’s what it was: her house.

My year in Sønderho is a cello’s sound inside me. I have only to glimpse the chimneys of Esbjerg Power Station and it begins to play. It sounds like an old-fashioned piece, Bach or Pärt. The silent space, a lonely string instrument, and then that long-suffering bending to the wandering of the moon and the clock of the tides. I love the Wadden Sea, though there’s something strange and sucking about it, and so I got a train from Amsterdam to Den Helder. There I rented a bike, despite the gusting wind. I wanted to get to Huisduinen and see the sign that marks: here begins the Wadden Sea. If you can say that something so strangely ethereal begins, and you can. You can see with the naked eye where that force takes over. In Denmark the transition is strongly felt along the west coast of Fanø and up toward Skallingen; the infinitely slick and grooved expanses pass from the south into something like a sea, lined with nearshore breakers. Nearshore breakers: the North Sea. Wide-flung tidal flats: the Wadden Sea.

Cycling to Huisduinen, I saw the transition there, too. Sand flats, lying in readiness, gigantic bars in the agitated water. This is where it begins, then: the Wadden Sea UNESCO World Heritage Site. The national park ends somewhere north, up by Johanne’s House, and I wanted to see this miracle take over from a southern direction.

“You don’t want to walk smack into a spinning top like that,” said my dad on the phone.

“But I’m so far from the storm,” I said. “It’s up near you lot. Not here.”

But storms have eyes. Their eyes are round, and they whirl. Grand Hotel Beatrix in Huisduinen has taken me into its fold. The hotel is located immediately behind the dam, a burly asphalted hulk, and on the other side of the northbound highway is the lighthouse, Lange Jaap, casting its bright cone into the pelting rain and sea foam. There is a storm blowing in Huisduinen. Lange Jaap sharpens and resists. Everything is black besides the light, sweeping rhythmically across the hotel. I’ve taken cover in my room. The building shakes. Small fox in the cave’s darkness.

Still, I did my best to make it to the dam before nightfall. I walked south with a scarf over my face. Grains of sand stinging, eyes watering.

I walked like a slash against the wind while the sea toiled against the disaster-proof dam. To the north, Den Helder, which so oddly mirrors Esbjerg back home, and a ferry bravely making the short crossing to the island beyond the town. It could have been Fanø, but it was called Texel. It’s the southernmost of the Frisian Islands, and Fanø is the northernmost. Island sisters, and I would have been there, but had to settle for seeing it at a distance. And finding the sign, and I found it:

WELKOM IN HET WADDENZEE

WERELDERFGOED GEBIED

WELCOME TO THE WADDEN SEA

WORLD HERITAGE SITE

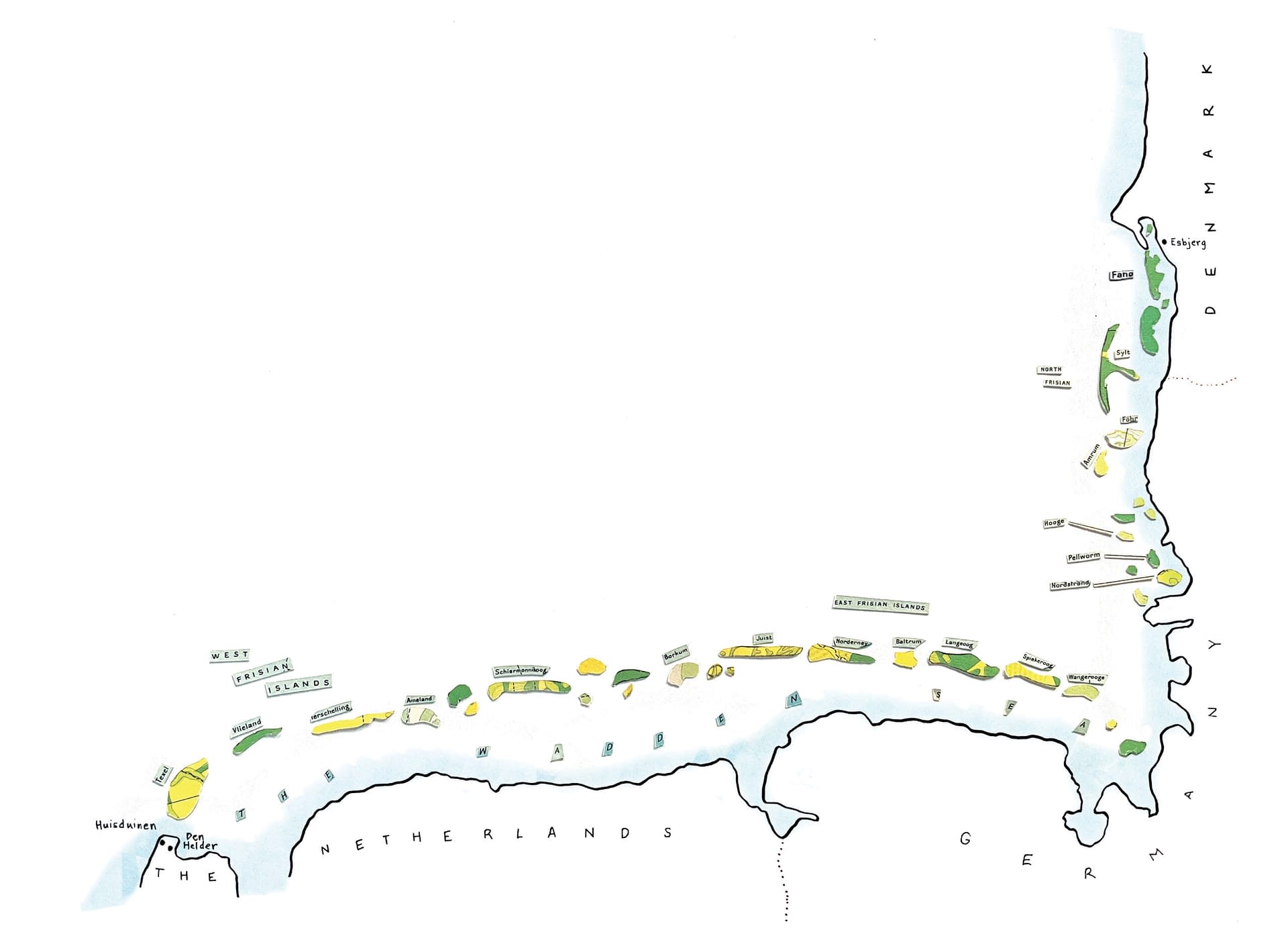

It’s warm here in the Beatrix. I’ve taken out a map. I’m looking at islands with funny names. To the south are the West Frisians, Texel the first pearl in the chain—or the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. After Texel come Vlieland, Terschelling, Ameland, Engelsmanplaat, Schiermonnikoog, Rottumerplaat, Rottumeroog, and then the islands known as East Frisian: Borkum, Juist, Norderney, Baltrum, Langeoog, Spiekeroog, Wangerooge, Mellum. They speak German now, call themselves North Frisian, and keep adding and adding, like pearls on a string. Then Pellworm, Hooge, Amrum, Nordstrand, Gröde, Langeness, Oland, Föhr, and Sylt. The language transforms slowly with each pearl, and suddenly they speak Danish. They call themselves Rømø, Mandø, Fanø, Langli. The chain is intact. No border can sever it.

It ought to be silent here, I think, under the duvet, listening to the fury outside. Silence and a stringed instrument.

The Wadden Sea is one large violin body that the water plays a few times a day, rising and falling, rising and falling. That’s how I pictured it the year I lived there. This silent suite was broken only by the fire alarm. In Sønderho on the southern tip of Fanø, the alarm went off at noon every single Saturday. For there are three things they fear in Sønderho: shipwrecks, storm surges, and fire. The town of shipmasters is thatched. Each house, except for a few lone contrarians, is orientated east to west. And thatched. Around them a system of paths and orchards. The idyll is absolute, Grade I listed. So every Saturday at noon, the fire alarm went off. That way you knew it worked should all hell break loose.

And then came the women. Since the siren was going off at twelve every Saturday anyway, they thought they might as well use it as a signal to summon the tribe. They slipped out of their gloriously painted shipmasters’ houses. They walked down Landevejen and Nord Land, Øster Land, Sønder Land, Vester Land. They darted, scurried, and strode down tangled paths through Sønderho, paths laid down by the coffee-thirsty. They steered a course for the pub, where a long table was set out for them. The stocks of draft beer and white wine had been kicked up a notch. The coffee machine was switched on and the Brøndum Snaps was laid out (Rød Aalborg is for the mainlanders) because there had to be booze-laced coffee, too, to keep everything going. And there they sat, the women of Sønderho. They settled their broad backsides around the table, becoming their own version of fire. Gossip set ablaze.

A kind of matriarchy, yes. Historically speaking, a small community where women held power. When the people of Fanø bought their island from the king in the mid-eighteenth century, they also bought their freedom and the right to international sea trade. They didn’t need to be told twice. In Sønderho, the men purchased big ships, declared themselves shipmasters, and set out like the Frisians they were to trade across the seven seas. They got a long way, the men of Fanø. They brought riches home. The shipmasters’ houses grew, flourished, acquired fantastical colors, garrets, windowpanes, and extensions. Sønderho transformed into a miraculous village, a community at once isolated and international, in the middle of a wayward sea. Sometimes the men were away for months. Other times they set out on long voyages and were away for years at a stretch before they came home. If they did come home, that is, for ships go down. And here’s how the situation worked out for Sønderho’s women:

Your husband is at sea most of the time. When he comes home, if he comes home, he gets you pregnant. On top of that, he must be occupied somehow. If he’s busy painting the outside of the house, he won’t be underfoot inside. So you put him to work.

“Why don’t you paint stripes above the windows, my friend,” you say.

It takes time, and meanwhile, everything carries on much as before. You’re used to running things. You farm. Keep animals. You, the children, the other women, and the old men help one another when he’s away. Sometimes you go, too. Sometimes you join your husband, your brother, your father, and see the world. But back home, it is you who decides when the hay should be harvested.

This is how it was. They settled things for themselves, the women, by and large. Decisions great and small, including those on behalf of the village—they took care of it all. Which was fine, and she looked forward to him coming home. Even though it was a hassle, his restlessness, the power struggles, and uncertainty. Four or five such years can turn a spouse into a stranger, near enough. And again, he had to be off. Gather, scatter. Gather, scatter.

If he did not come home—that, too, was dreadful. Then she was a widow in a village of many widows and unmarried women. But the widows and the spinsters moved in together. They took care of one another and the children. They drew an ingenious system of paths between the houses of the elderly with their feet. A cottage industry sprang up, dealing in mutual care, preserved fruit, salted fish, gossip, social control, and money. While the straightening of the river Skjern shows what a landscape looks like when someone’s been at it with a level, you should look at Sønderho to see how paths arrange themselves under women’s feet: organic as the roots of trees.

The sign of Fanø’s matriarchy was their dress. Fanø’s men just wore clothes: wooden shoes or boots, wadmal, and a cap. But Fanø’s women wore a uniform. It didn’t emerge out of thin air—it emigrated from the south, like their architectural style, their genes, their merchant zeal. In other words: it was Frisian. If you disregard the trading town of Ribe, where you could sell your fish, Fanø was more orientated downward, toward its sister islands, than toward the Danish mainland.

At the top of the uniform was a scarf simply called a cloth. Its bow had to be knotted in a particular way that made it look like a sail. Frisian woman: sailor wife. There was no shortage of skirts because it was important to create wide hips underneath a narrow waist. The jacket was buttoned up if you were unmarried. If you were married, a single button was left undone. There were various versions of the garments appropriate for various phases of life. Little girls learned at around seven years old to tie their cloths, initiating them into the tribe. The women’s garb was roughly the same color as the houses, so in principle he was also mending her if he came home. And if he came home, they danced together. They danced one of the most beautiful traditional dances on Earth: the sønderhoning.

It really has to be seen, but this is how it goes: First they walk hand in hand, then he reaches both his hands around her, behind her back. Putting one of her arms behind her back, she grabs hold of his arm. The other arm she places lightly around his body. Then they whirl like scaled-down dervishes across the floor. They have each other caught by a centrifugal force. Like a North Sea depression, with its silent eye and its wildness at the periphery. He clasps her firmly, as though she were life itself. She allows it, and looks determinedly, not coyly, at a slanted angle to the floor. For he has a solid grip on her, the man, but he does not own her.

The first time I saw a young couple spontaneously take to the floor and dance the sønderhoning at a pub one chance night when someone happened to have brought their violin, I was moved.

“Oh, that’s just beautiful,” I said to the others at the table, who then got up and danced, too, as though it were quite an ordinary thing to do at the end of the world one weekday night: to dance a dance so simple and powerful that it has survived for generations. The young people look like it comes to them naturally. I don’t know if that’s true, because it’s difficult, and where I come from we were forced to dance traditional dances at the community center, after which we immediately forgot them. There’s a community center in Sønderho, too, where they might have been made to learn, so maybe somebody pushed them through it. But as adults, they look like they wanted to dance of their own accord. I tried, but the man I could have danced with was absent, and anyway he had committed to dancing with somebody else.

I wonder how Texel, beyond the hard-boiled dam and the water, feels about the mainland. Was it, like Fanø, reasonably indifferent until it was reduced to a place for vacationers and romantics from the capital? Are they still full of wanderlust over there? Opportunistic, die-hard, self-assured? Does the Wadden Sea tug at them the way it tugged at me the year I lived in Sønderho, still young and full of illusions? It affected you, the Wadden Sea and its tidal pulse. The natives knew that. Births got underway as waters rose, they said. Those due to die died when the waters receded. You could read it in the obituaries. So-and-so died late Tuesday night “at falling tide.” That was important to include. God was one thing, the Wadden Sea was another, and the two things could scarcely be separated.

I used to walk down Nord Land every night, up to the dike, listening. The starry sky formed a dome above the island, vast, curved, and infinite. As I stood there, I sensed the depth of this curve. Up and down became relative terms, and when I shut my eyes, I could hear the silence of the Wadden Sea, like some kind of resonance. North, the sound of breakers taking over. A deep bass sound of currents and snapping water. But to the south and southeast were the flats, and through the flats ran the enormous underwater trenches, the deeps. These channels and their tributaries, the tideways, ran like juicy veins into the mudland. Unseen, almighty, they wove quietly in and out, in and out of the Wadden Sea, like blood supplying a placenta. The deepest trenches had been given names, the seriousness of which was understandable—Knot Deep, Gray Deep, Gallows Deep—and the Wadden Sea became a huge basin beneath the vaulted stars, where everything fertile grew, including death. Perhaps the cello’s sound was coming from the deeps, from the tideways. Perhaps I’d brought it out there myself. Perhaps it couldn’t be any other way.

The lighthouse rakes its beam across the sea, and I have set the map of the Frisian Islands aside. I’m looking at old photographs from Fanø instead. It’s safe that way, and what I see in the pictures is the way they carry themselves in nearly all of them, the women. Wrapped in cloths, padded, wide-hipped by their underskirts. Their jackets narrow across their chests, their faces hard as leather. They stand at one end of the house, gazing confidently at the interloper.

These are Johanne’s foremothers. They stand in front of sand dunes, swollen orchards, and buses. Johanne once told me that her ancestors were Frisians from the south who had settled on Fanø sometime in the seventeenth century. They’d been living on the island so long that her grandmother, as a child, had been painted by the well-known Fanø artist Julius Exner. The portrait hung in Johanne’s living room. Grandma as a little girl, with a pretty cloth, already initiated into the tribe. As I recall, there was a cat in her arms as well. Inside the wardrobe, the grandmother in the painting rose from the dead in the form of traditional Fanø clothing: the clothing Grandma had worn when she became a grown woman. To Johanne, the clothing was sacred. Every year on Sønderho Day in July, people told her she should put it on. She didn’t want to. She didn’t like the way the mainlanders and vacationers, slightly too rich and privileged, played dress-up in her foremothers’ costumes. The garments were deeply serious, and not just something to wear for carnival one day out of the year. They were dolling themselves up in borrowed plumage, Johanne felt, and on the whole, I thought she was right. The last Fanø woman to regularly wear the clothing died in the seventies. The exodus from the outer periphery to the big cities had begun. The era of the shipmasters was long over, and so was the matriarchy. From now on, the women were supposed to have children to keep the local community alive. The young women on Fanø started to wear miniskirts and bell-bottoms; they styled their pageboy haircuts with curling irons. They were wrapped up in the number of pregnancies, both theirs and other people’s: the survival of the school, of the greengrocer. But the city slickers wanted to have their fun with the passing of time: they played at the old days, marched in processions through the city with cloths bristling and hips rolling. Johanne, sweet person that she was, put up a quiet resistance. Grandma’s clothing was not to be sullied by vapid tourism or people who didn’t understand what it meant.

For it meant more than just power. It meant longing, hard graft, vulnerability. And it meant that you lived with the Wadden Sea, in birth and in death. That you realized what those great flats gave—life and rich growth, wildfowl, glasswort, amber—and what they took from human life. Grief came with the privilege of wearing the clothes, and coffee laced with schnapps wasn’t just about standing one’s ground stoically against the cold. It was also medicine to combat the forces of Gallows Deep.

In the storm outside, between Texel and Den Helder, are the underwater rivers of Marsdiep and Het Nieuwediep, and somewhere near the harbor you might run across a pumping station called De Helsdeur—Hell’s Gate. They understand, the West Frisians, that this landscape is bountiful one minute and all-consuming the next. It is the job of Hell’s Gate to try to keep hubris at bay. I hope it holds tonight while I look at pictures. There’s one of a Fanø woman by her neat picket fence. There’s one of a Fanø woman with her daughters in tow. There she stands where she can, and she’s in the center. In one of the pictures, you sense this woman’s presence to an almost supernatural degree. It was taken on Fanø Beach one February day in 1915. A group of women in Fanø dress have gathered like cormorants in the cold. Maybe they’re posing for the photographer, their cloths fluttering in the wind. Maybe they’re making sure nobody gets any closer. Behind them is an enormous sagging German zeppelin by the name of L3. It has just been on fire, and as the women stand there, they seem to be keeping watch over the burning. Only the day before, this zeppelin had been a giant, making its way from Hamburg to Skagerrak to scout for British submarines. There was a war on, of course. And then came the southwest storm. It set in with snow. The zeppelin drifted in the wind, the engines battling to no avail. Half an hour north of the German border, the last one gave out. An emergency landing in neutral territory on Fanø was their only resort. From the safety of the beach, the Germans shot a flare into the airship, setting it alight. Flames and curiosity had drawn these women. They are of another world, standing there. No, they were of another world.

I don’t know what Johanne thought when the fire alarm went off every Saturday, gathering the women of Sønderho at the pub for a drink and a gossip. I think she thought it was nice. She used to go along, at any rate. At Johanne’s house, I’d often sit and chat with her about anything and everything. Even after I left the island, came home from the U.S., and moved to Copenhagen. My wanderlust took over. The schism in which all identity is formed made me set out.

The water rose and fell, the pulse beating the hours of the day. I know that good souls around Johanne eventually prevailed upon her to wear her grandmother’s clothes, just for one day of carnival. If anyone was going to wear it, she should be the one. And she was proud of it, after all, she told me on the phone. She’d felt strong and beautiful in it, and I wish I could have seen her. But I never did. The last time I visited Sønderho, it was for Johanne’s funeral. That day no one wore Fanø dress, but the grief, that was real.

At coffee after the funeral, we sang the song that’s always sung at gatherings on Fanø. Gather, scatter. A song that mimics the tides and the comings and goings of the world. A people with wanderlust aren’t afraid to sing in chorus, “The time has come to travel, friend—my path to distant lands I wend.”

To that song, my hinterland family would have moaned, “Ghastly.” In their circles, they sang, “The Jutlander, he’s strong and tough, and he will not be moved.” But my grandfather’s family was full of fjord fishermen, and my great-grandfather was a shipwright in Esbjerg. I have no doubts about my refrain: Überläufer.

After the wake and the booze-laced coffee, I walked through Sønderho and out toward the southern tip. It was September, the sky was high, and I pressed on across the flats. I walked in the direction of Gallows Deep, talking to Johanne. I don’t know if she died at a falling tide, but I know she had the Wadden Sea so deep down inside her soul that she couldn’t possibly be anywhere but here. And so I stood, listening to the silence some way out, the stringed instrument. Ribe Cathedral a vast omen to the east. Feeling the vault close below me and above, I crouched down. I took a handful of wet sand and let it wring out through my fingers. The Wadden Sea is a living being with a big, damp lung.

“For the men we couldn’t count on after all, Johanne. And for the tenderness we felt for them anyway,” I whispered, leaving my handprint in the mud. I could have sat there for a while and seen it erased by the tide. But the tide comes in quickly in these parts, and we must gather, scatter. Welcome and goodbye.