I cannot say I fully understood where it came from, but I think we all understood, in a way, where it came from. Not physically where it came from—I mean, no one could really explain that—but the mountain’s sudden appearance was at least understandable from a metaphoric, philosophical, and/or emotional perspective, which is to say it made sense astrologically even if it did not make sense logically.

Logic and reason (remember reason?) had long ago fallen out of fashion. The calm among us—and there were still a few calm among us—kept saying there was no need to worry, that history was cyclical and we had simply entered a recurrent era of abject chaos. This was the “Goodnight Mush” part of the century, time for the chrysalis to turn soupy. This was the year a mountain spontaneously materialized in rural Kansas, one kilometer high, composed entirely of semiconscious adult men.

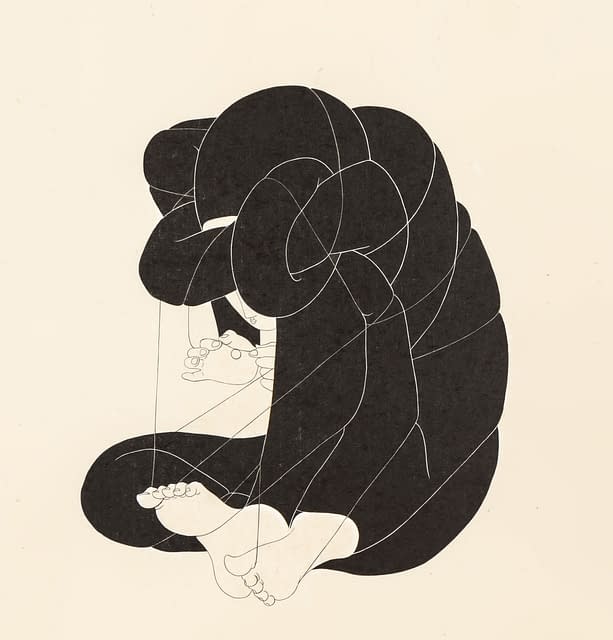

When I heard about the Man Mountain I was, of course, at the gym. Those of us who were not comforted by the historical view of the contemporary moment—a nagging sense of being prewar—had taken matters into our own hands in the only way we could—that is, symbolically—and began training for the figurative and literal wars that were both imminent and present. Most of the women I knew (though I only really knew or seemed to know the people who also spent most of their waking hours at the gym) kept strict training schedules in Muay Thai, jujitsu, boxing, or semi-acrobatic styles of weightlifting. In an era of perpetual crisis, we soothed ourselves by caring inordinately about how tall a box we could jump onto, or how much we could deadlift, or how many times we could flip a truck tire. In idle moments, we imagined perfecting the form of our pull-ups, our push-ups, our jabs and jump squats, and we pitied the women who still did yoga, except the ones who did that torturous heated variety with their tongues sticking out, contorted and menacing and psycho-spiritually weaponized. They were alright—mostly—though we felt they had not yet realized that inner peace was a patricapitalist fantasy and the only reasonable thing a woman could do now was amass an anti-estrogenic cluster of meat around her controversial guts and train for battle.

“Our Bodies, Our Machines,” we said. There was no time for softness. There was no time for time. Sometimes, between sets, we would look at each other and just say what year it was—could you believe it? And no one could believe it—then we would return with new hostility to our routines, laboring until we were sweating blood, spitting blood, until blood soaked our hair and slicked our limbs, until blood issued from our every pore and pit.

So when news broke about the Man Mountain I just thought, Uh, what? Then, like so many unbelievable things, it became completely believable, and all there was left to do was to climb it.

Not to blow my own horn (but also not to apologize for blowing my own horn because what else are you supposed to do with your own horn) but I probably ranked in the top tier of nominally amateur American athletes most prepared to conquer the Man Mountain. I don’t know how you could have polled for that, but I feel confident that it was, and still is, true. I’d spent a lot of time at my local climbing gym, then a few other climbing gyms, then I went rogue and started climbing straight up buildings, trees, gates, traffic lights, anything. Maybe I didn’t have time to eat solid food anymore and maybe I wasn’t being an effective employee and perhaps I didn’t have an actual human-on-human relationship in my day-to-day, but none of that mattered anymore because I was no longer exactly human, but something closer to a spider—spindly and silent and menacing, frightening nice people as I hoisted myself onto their balconies.

So I drove straight to Kansas and, uh, whoa. The pictures and the videos and the three-dimensional animated renderings of the Man Mountain did not really convey the thingness of this thing. It was a real stumper. It was, I don’t know, a feat? But whose feat? A feat of what? Several television trucks were there, but none of the reporters could look away for long enough to read their teleprompters. Policemen and National Guards and SWAT teams idled in dark hordes, but there seemed to be no agreement about how to proceed—which way to point the guns, whether it was a crime scene or not, whether the Man Mountain needed protection from the people or whether it was the other way around. Some UFO enthusiasts had gathered, smug and reverent, and there were several varieties of cult members and leaders, many forms of clergy, druids, leftover Y2Kers, a few seemingly unaffiliated drum circles, and so on. Each of them claimed the mountain as confirmation of whatever they needed confirmed; it had been prophesied, and now was a time for great rejoicing and repentance and sudden death. They looked up at the large Kansas sky, gleeful and reassured.

I stood away from the crowd. An expectant solitude washed over me as I contemplated the possibly sinister and as yet unknown force(s) that could have created the Man Mountain, and my understanding of the basic foundation of reality shifted beneath my feet. It was reassuring, at least, that something literal and serious had occurred in this time of chronic indifference and rumor. The Man Mountain was not contingent or theoretical. It was not a think piece. It was here and large and undeniable. The few who attempted to take photographs of the Man Mountain all failed, as the feeling of being in its presence resisted digitization. It was the only event for many years that lacked an obvious political narrative or conspiracy or apocrypha.

The base was exceptionally easy to scale, almost as if it had been designed this way. Holds were plentiful and well spaced. I grabbed a foot, an elbow. Thighs and buttocks gave gently beneath my feet. Up close, none of the men seemed to be asleep, exactly, yet none were quite awake. Most of their eyes were shut or fluttering, and all of them held slight grins, as if they understood and accepted the strange enormity of their predicament. Every limb I held as I scaled seemed to teem with itself, forcefully occupying its place in the pile. There was no passivity here, no victimization. The Man Mountain was, I inferred, a wonder of sheer will.

About thirty feet up I came across Justin.

Justin? What are you doing here? Whoa! Justin!

His eyes shocked open like a corpse in a horror film, which would have startled me if I hadn’t been engaged in military-grade stress training for several years. Justin began to move his mouth, the muscles as loose and uncontrolled as an infant’s.

Hey.

Yeah, I said. Hey.

A broad man sandwiched sideways in the mountain created a ledge I rested on to talk to Justin.

It’s been a while, I said.

Yeah, he said.

Are you alright? Do you want me to, uh, help get you out of here or . . . ?

Nah.

Cool. Okay. Well. Maybe I’ll see you around?

Justin didn’t reply so I kept on moving upward, but what did I even mean: Maybe I’ll see you around? Around what? Around when? Recently my emails had started writing themselves—I would click to open a reply, then the computer would just take over and words appeared on the screen, words I recognized as unremarkably my own. Even our emails knew, for absolute certain, that no one had said anything unpredictable in many years.

And when, exactly, had I even met Justin? I couldn’t remember if he was someone to whom I’d given my vague approval or whether he was someone I suspected capable of performing the acts of evil so casually enjoyed by those with disposable incomes and frictionless societal existences. I was pretty sure we’d met at a party hosted in a town house owned and renovated by a tech start-up. A large fiberglass horse took up much of one living room. It seemed several young men lived there, and several maids would appear and clean it when one of those young men summoned them through one of the apps that had been developed by the start-up they’d started. A grove’s worth of potted fig trees filled the rooms, all of them well cared for, some of them fruiting. One room was arranged with sofas and armchairs that looked like the cartoonish, inflatable furniture sold in late-nineties American malls, only this furniture did not deflate. These chairs, you had to live with them.

Justin had been playing a vintage pinball machine under a black crystal chandelier while explaining some complex opinion to another man, or maybe Justin was the one listening instead of speaking or maybe Justin and I observed these two men by the pinball machine or perhaps Justin was someone else entirely. It’s difficult for me to remember, as this was a very long time ago, at least one presidential era into the past. In fact, Justin may not have been either of those men but instead the one who had either invited or escorted me to the tech town house, and if that is the case then I am even less sure about how I first came across Justin and now that I think of it I am less sure about his name being Justin, or—another likely case—half or more of the men in that town house were named Justin. At the time I thought an important part of being a human was appearing before other humans and demonstrating the facts of your humanity—your name, age, origin, collegiate affiliations, career, ambitions, social standing, and whether you slept in a bed with another person and if so what sort of genitalia that person had and if not what sort of genitalia you would accept on the body of a person with whom you might consider sharing a bed.

But then I joined a gym and realized that it is totally possible to commit to a life lived primarily within one’s legal, corporeal limits, and of pushing one’s living corpse to the outskirts of its abilities, of measuring out the finite weeks in leg, arm, back, or ab days, of monitoring the fluctuations of a body fat percentage, of scrupulously observing the material intake and output of one’s body, of tracking the incremental progress of how well one is able to pick something up and put it down again. There was nothing, it sometimes seemed, that I couldn’t lift and set down again, nothing I couldn’t climb, nothing I couldn’t put below me.

Anyway, I soon realized my ascent of the Man Mountain was going a little too easily—it just wasn’t the challenge I’d been hoping for as I wasted all those hours driving to Kansas. In boredom, I stopped on a man situated horizontally in the pile much like the man I’d perched upon to talk to Justin, and in fact this man looked so much like that last man that it might have been the same man and turning to my right I found, again, Justin’s face, his eyes just as wide as before.

Hey, Justin 2 said, but I could not bring myself to reply. Had I somehow climbed in a circle? I had, I thought, been climbing straight up. I looked down at the spectators and SWAT teams and television trucks below; everyone was still staring up or moving around haphazardly, pacing, confused, aimless. I leaned back against the chest of a man in a pale green polo shirt. Hey, Justin 2 said again, but I didn’t have any ability or desire to speak to Justin 2 for the first or second time. Something was not right. Something, maybe, was very wrong.

A foot jutted out right next to my head—it wore a polished leather shoe and a sock patterned with little red and blue birds flying to and from and with and against one another. The ankle of this foot seemed to be in good condition, probably had a decent bone density, healthy ligaments. I’d once seen someone drop a sixty-pound metal orb on his bare foot and as the orb rolled off, his foot seemed smaller than ever, but by the time the ambulance came the foot had swollen to the size of a small head. The guy on the other end of that foot was stuck in bed for months, losing all his life’s gains, all his strength evaporating in his inaction. To get out of bed he needed permission from both his feet

and one of them would simply no longer give it. His foot, it seemed, could not forgive him.

And what part of my body would someday not forgive me? I often succeeded in never thinking of such things by thinking instead of inputs and outputs, measures and reps, by focusing on progress and never on ends. But here on this heap of men, everything seemed closer than ever to ending, and all at once I was engulfed by a great arbitrary vortex that goes by the name of God.

All those heights I had climbed, all my strength, all my effort and torn muscle rebuilt and rebuilt, not even God could see it, and I knew that then, or I felt that I knew it, or maybe I just felt a breeze and knew it to be the cool and apathetic gaze of God. I was in a race against my own potential weakness and I was winning and I was losing.

Hey! Justin 2 said again.

No, I thought, that’s quite enough. I simply cannot tolerate being so social anymore, not today, not in this crisis. There were just too many people in this Man Mountain, and I had not come here to make friends—I had come here to climb! Well! I wasn’t going to waste my little time any more. I started scaling down the Man Mountain, which is always awkward-looking and never quite as easy as going up. I passed the initial Justin, who calmly watched my descent, but then I passed Justin again, and though I quickened my pace, I passed yet another Justin or perhaps the same Justin and when I looked down to estimate how close the ground was, it seemed I hadn’t moved any closer to the base

of the mountain.

Then, as if this world had spontaneously begun to understand my trouble, a rope ladder dropped from a helicopter. I leaped to and ascended it, and how strange it was to realize that climbing something as unusual as a pile of men could be so boring while climbing something as unremarkable as a rope could be so thrilling. The wind whipped up by the helicopter blades rushed through my four actual and my four invisible limbs and for a few moments everything I’d ever done seemed worth the hassle. God could take me or leave me.

In the helicopter several reporters were huddled, and one of them had a large microphone she held to my mouth as she shouted questions over the helicopter’s nearly deafening whir: What were the Men of the Man Mountain like and what were they doing there in a pile like that and what did I think it meant and did I think the federal government should intervene or should they leave it up to the state of Kansas and what would I like to tell the American People and did any of the Men in the Mountain say anything to me and did I say anything to them and did I suspect foul play or divinity and, yes, most importantly, did I think the Man Mountain was an Act of God?

I wanted to answer the reporter, but I didn’t want to answer her questions. I shook my head, so she re-shouted her questions, all of them the same, just louder, meaner. How could she have known that I, a human spider, can hear very precisely through both my ears and the extremely tiny and biologically complex hairs that cover my body and limbs? She couldn’t have known. The truth is that spiders and humans know very little about one another, and human spiders know even less about themselves. I tried to answer her questions, but my ears were bleeding. I’m simply too sensitive. I just want to climb on everything, keep climbing on everything up and always up, to reach the top or die trying. I tried to speak; I may have spoken. Perhaps I should have kept quiet. Below us everyone kept struggling and failing to know how the world had come to this, and above us no one even bothered to ask the question.