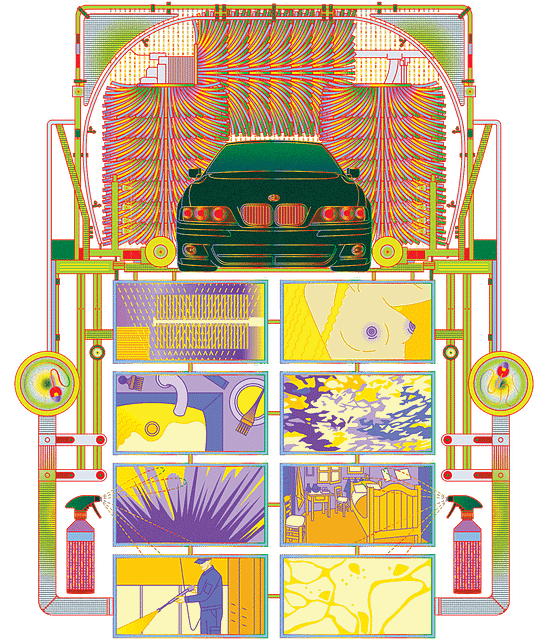

Droplets pull and push against the glass, moving in every direction. The air is blowing on the glass and then the water is rushing. A piece of light plays against the windshield, forming shadows on the dashboard, the seat, and Bruna’s dry hands.

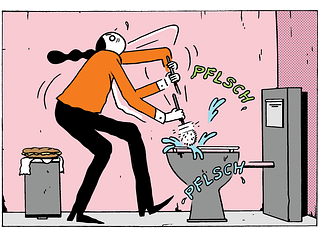

The water is rushing, rushing out against the green car, a 2003 BMW 540i. An artificial typhoon is summoned, loud against the metal. Bruna is reminded of a baptism. The vehicle is submerged. She thinks of holy words: thou, doubt, shall, unto, save, whole, thee, obey.

Bruna’s mouth is open and the phlegm is resting in her chest. Bruna is often sick, coughing, or otherwise scratching her throat. So that’s how she is in the car wash: nose stuffed, sitting, scratching her throat. In front of her: a Nissan, a Volvo, an Alfa Romeo. Bruna touches the orange sweater around her neck. She’s sick. Or she’s been crying and her nose is stuffed. Her lips are dry and her tongue is dry from breathing through her mouth. She can’t smell the leather seats or the tree-shaped air freshener swinging in her peripheral vision.

It’s nighttime. Bruna watches the road from the reflection in the rearview mirror — blurry people on their way to work, or to the fish section of the supermarket. Behind the Nissan, the Volvo, the Alfa Romeo, and the 540i there’s the sound of a motorcycle rushing past the car wash on Boston Road. The cars inch forward, the fluorescent lighting in their eyes. They lift the beige visors, folding them in place. They shut off their radios. They listen to the whistling of the phlegm in Bruna’s chest, the air behind her teeth as she breathes, and the tracks that are moving the sixteen tires forward.

The soap falls. Despite having been raised in the church, Bruna no longer remembers how religious words fit together — in the name of the Eucharist, all glory is yours — she can’t remember, not any of the verses of the catechism, or how the voices of the Corinthians might sound. Ashes were placed upon her forehead as an adolescent, and she knows the pressure of a priest’s finger on her skin, the ashes falling onto her nose, the pipes of the organ, the dark mark small and illegible.

The 540i is pulled farther into the tunnel. The track underneath is clunking, clunking. Bruna watches the soap moving on the windshield, moving like unsalted butter in a nonstick pan. Moving down. In semicircles. Up.

It’s quite beautiful. If someone were in the 540i with her she would tell them. She would pause and tilt her head to the right, breathe in, sigh, breathe out through the mouth (as her nose is unwilling to open for air). If someone were with her she would want them to notice this tilt of her head. She might offer it discreetly: “It is quite beautiful?”

Bruna is alone.

Except for the car wash attendant, Bruna’s alone. The other cars are gone: Nissan, Volvo, Alfa Romeo. She’s the last and it’s late. Earlier, hours before, when she’d handed the car wash attendant the discounted fee, he chose not to meet her eyes.

Droplets of soap continue their swimming; under the fluorescent lighting it’s reminiscent of the moment after sex, when the fluid drips down Bruna’s thighs, dripping, smelling of hydrogen peroxide. Or when it lands on the edges of her purple nipples. Her purple nipples are sore and swollen as she sits in the 540i, as they usually are during this time of the month. She is menstruating, and the smell in the car wash tunnel is unmistakable — hydrogen peroxide.

She thinks of her mother and of the name her mother decided to give her: Bruna, Bruna, Bruuuna. As a child, Bruna heard it being yelled in frustration. Her mother didn’t like the name, it was a name chosen to encompass her strong distaste for this child, a child who looked only like the father.

Bruna means dark-haired, dark. The name reduces her to her most obvious quality. Bruna was born with a dark mane of hair. She sometimes calls herself Una. Or Runa. Or Brun. Bru. Br. Na. Run.

In the 540i, Run’s hair is no longer dark. It was dyed yellow, with a bottle of bleach and peroxide it was dyed.

Yellow is the complementary color of purple, Run thinks, and so she’s delighted that her hair complements her sore purple nipples. As a habit, Run will sometimes touch her nipples while watching television in her bedroom.

Bruna’s yellow hair is stuffed in the mouth of her orange sweater. This creates the impression of short hair, the length being something she can reveal or suppress as she chooses, the artificial yellow.

Van Gogh used an abundance of yellow and purple in his paintings. Run likes The Bedroom, with its violet walls and yellow chairs, and so she sometimes calls herself Van.

Van chooses not to show the length of her yellow hair to the car wash attendant. His hair is dark.

The mitter curtains approach, swaying and swinging like a drunk. Then they are upon her and up on the windshield of the 540i. With a loud thump, the curtains cover and uncover the glass, darkness and light alternating, the curtains standing, lying down, standing, hesitating, lying down again, heavy and indecisive on the windshield.

Van wonders what the car wash attendant thinks of this car-washing technology, if he finds his job ridiculous, if he considers it unskillful when he prepares for work in the morning. If so, Van doesn’t agree with his impatience, she believes the job is functional.

Van has been conditioned to be complimentary and to sit still, for God’s sake, which is how Van sits now in the 540i, knees touching, ankles crossed, head leaning.

The car is pulled forward and Van shifts in her seat. There is discomfort in having been conditioned to sit so still, for the sake of God. Some sound startles her and now her knees are apart — a harlot’s gap.

The soap and water drip down like holy water.

“Rain sometimes contains hydrogen peroxide,” Van’s male boss once told her. “The dripping is like seminal fluid, or the first milk, colostrum, which contains peroxide, too.” In the small office kitchen her male boss had whispered in her ear, “Colostrum helps the immune systems of babies.”

The chemicals, the foam, disinfectant, air and water, hydrogen, the spermatozoa, the weak immune systems of newborns, oxygen, and the long strips of cloth moving all of these things around.

The 540i, forest green, continues forward. Van’s head leaning back, she watches the car wash attendant in the rearview mirror.

There is soap and then it’s gone, the water returns, hitting the car, pounding the car with air, drying, and then the dirt. She has paid a dollar extra for this dirt service. She’s paid a total of six dollars.

The dirt comes from the car wash attendant: mud and sand, grease and oil. He throws buckets of it on the windshield. It’s on the glass, on the windshield wipers, the green car. Van thinks of abandonment, of a man who left her only for the look of her hands, not for another woman, as her family had first believed, but to live the life he felt he deserved.

Van thinks of hourly wages — the average car wash attendant makes $11.49 per hour. She wonders what the dark-haired attendant might purchase with $11.49. His hair seems healthy, his hands seem youthful, and she thinks his name might be like hers (or how hers used to be) if his mother had chosen to reduce him to his most obvious quality.

Bruno buys eight caramel-filled candy bars for $11.49. Bruno buys a small piece of land near the car wash, a very small square of it. He stands on the square with one foot; he has a strong core to help him balance, and he switches feet every few hours.

“Get off my land,” he would yell, “this here is private property.”

Van coughs and the phlegm makes itself known. Her nose is closed. The forest-green 540i is now brown and forest green, and the attendant, Bruno, seems more attractive than she had initially thought. Van removes all of her yellow hair, dry and brittle but long, from the orange sweater. She watches Bruno notice her movement despite the layers of dirt covering the car. Van’s sore purple nipples don’t show through the orange sweater, but they are there, and they both know it is so.