Fiction The Filth issue

Eat the Other

By Ananda Devi

Translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman

TO READ THIS STORY IN FRENCH, click here.

Let us turn to the facts.

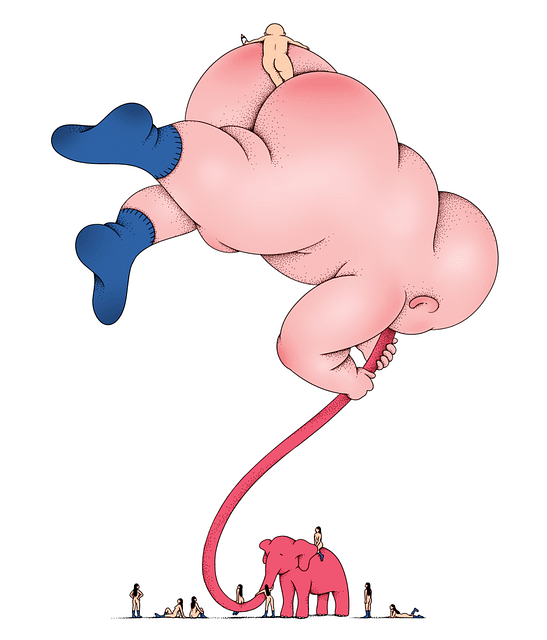

After nine months and ten days precisely, those ten days having felt as long as the preceding nine months, my mother gave birth to a pink elephant.

It weighed twenty-two pounds and eight ounces, which wasn’t an excessive weight for a baby elephant but was a record for a baby human. At the moment of delivery, my mother finally let herself feel the surprise she’d repressed during her entire pregnancy, even as her slim body had taken on monumental proportions: she shrieked like a madwoman.

I was the pink elephant. I didn’t have a trunk or huge ears, but it was impossible to reconcile my body with the word baby. It would take some other word to describe me. My mother bawled her lungs out, but the doctor and the nurses were speechless in turn, filled with a consternation owing not just to my excessive weight but also to my appearance as a Chinese Buddha with an unmoving, cynical gaze.

They were swift, I am told, to abandon me in the arms of my mother, who was the most dumbfounded of them all — physically, morally — by the reality of my existence, as well as its singularity. I think I can remember a stubbornly empty room, populated solely by my hunger’s roar.

I imagine a hospital reverberating with these echoes and screams. I think about how everyone, faced with the unthinkable, flees: an abnormal, impossible-to-love child. Maybe it would have been better for me to have been an actual elephant born from a woman: that way I might have become a circus freak, arousing curiosity to make up for the lack of love. I would have been the darling of the internet, where everyone, eager for the latest news, would have followed my development wholeheartedly.

I think I remember a haunted look, too; no doubt my mother realized there was no turning back now, no way of ignoring this reality, no escape, no denial, she could never say no, this baby isn’t mine, you made a mistake, the nurses gave me the wrong baby, they all look alike, don’t they, but a mother’s heart always knows the truth, this newborn isn’t mine.

Of course: they don’t all look like one another because I don’t look like any of the others. No way to hand me off to another mother too distracted to notice. She was done for.

My cumbersome entrance was marked by that defining quality of the entire human race: a fall. The day after my birth, my mother, still throbbing with the pain of her cesarean section and the shock of this giant baby that had come from her devastated body, tried to get me out of the cradle. She did not realize that these twenty-two pounds of swaying flesh supported no muscles. She leaned down, slid her forearms beneath my swaddled body, lifted me up. She felt her back straining as she stood back up with me in her arms. Her stitches stretched and snapped. Unable to take a step, she staggered and crashed to the ground, shielding me from the fall with a painful twist of her body. (I’ve wondered whether she hadn’t regretted this instinctive act of preservation later on.)

She stayed like that a long while, a dying cow sprawling across the greenish vinyl, while my mouth, furious yet furtive, mechanically sought her breast. She fed me, a cow laid low by the enormity of her work. Her scar had opened back up. The blood poured forth just as her milk did. Her innards filled with acid. She cried, she who had never cried. I’d pushed my strong mother, my beautiful mother, my high-heeled and short-skirted mother, my professionally successful American mother who refused to be shaken by anything and who still did not understand that her female body contained so many traps, to her limit.

I think she saw me from then on as the one who had brought her low

with her mere existence, who had warped her gleaming warrior-like trajectory. She now found herself horrifyingly diminished, her hair greasy, her nightgown pulled up over her now-heavy thighs, her belly sagging — a vision of ruin — in short, an unbearable regression to the status of a woman reduced to her role as a bearer of children, in that dark time when women were simply wombs, mere envelopes for the offspring that might be wanted in the hazy future; she had reverted to a female ruled by her biological clock; the best thing would have been for her to have her uterus removed in order to enjoy tranquility. But had she really had the choice to do so? Had she really made that decision with all the cool precision of her ten-year financial projections? No, no, no. She had followed her animal instinct: procreate or die.

How could she have loved me in these circumstances?

In the beginning was a ravenous pink elephant seizing all its mother’s life and body. I never stopped begging to eat. I spent my days latched onto her breast. My only possession, my inalienable right.

I was born with no aim beyond feeding myself. And as I could not do so alone, this Sisyphean work became her responsibility and her burden.

My poor wan mother, withered by her belly’s brutal deflation, ill-prepared for such an eruption of fury in her orderly existence, tried her best to sate me.

But nothing sufficed. My mouth was a cavern. More, more, more, screamed the royal baby, the red-cheeked tyrant, the sumo-shaped conqueror.

Not an hour went by without my begging for her breasts. The pace became hellish. The more I grew, the more she shrank. Her teats bore traces and crevasses. She grimaced each time my open mouth drew near, anticipating the pain, tensing as she considered her poor, swollen nipples, with their blue veins, their pale blotches, their pinkish wounds, their sticky runoff.

How do the cows do it? she wondered. Worse still, how do dogs and pigs do it, with their litters, all those little mouths begging — is that what I’ve become? If that’s what’s come to be, why do I have only two teats?

She was convinced I was devouring her. Maybe she wasn’t wrong.

She ended up weaning me off, preferring to let her affluence run dry in order to give me the baby bottle. She would mix cereal in beforehand. To keep me going between two meals, she said. The doctor had officially told her not to, but he wasn’t the one who spent his days and nights feeding me. So she kept doing it, with the feverish feeling of being a poisoner. Unfortunately for her, my stomach accommodated this new diet easily. She kept on supplementing my bottles with cereal; I kept on crying for more and growing. This logic carried the seeds of its own defeat, but she could not have guessed it.

In the beginning was an incontestable divinity: me. Outside the hospital, people exclaimed upon seeing me in her arms or in my stroller, certain that they were admiring a baby several months old even though I was only a few days old. And so I was, briefly, a magnificent newborn: the empress of infants. I was dressed in lace and broderie anglaise. My cheeks reddened in the air like spring blossoms. I contemplated the world as if it were my kingdom. My gurgling was so close to babbling that nobody was shocked.

The honeymoon was short-lived. Very quickly, everyone’s gaze lingered as the superb baby displaying its love handles and folds proved itself to be nothing more than unsightly flab. The weight of that judgment bore down on me, and doubly so on my mother — after all, I was innocence itself, not having chosen to be born an elephant. My mother turned a deaf ear. She knew instinctively that the battle had been doomed from the start and that she wouldn’t have the strength to fight against my needs. I’d won even before realizing that we were enemies.

Perpetually interrupted nights can turn the most even-keeled women into hysterical harpies. The weeks went by; I suckled as I heard her gnashing her teeth and whispering curses. One night, having hit her limit, she pinched me sharply right in the middle of finishing my bottle. The baby I had been was momentarily puzzled: Should I express my pain with a cry and thereby let go of the baby bottle, with its marvelous taste of rubbery milk? Or should I ignore it so as not to interrupt the practically aphrodisiac flow of sugary liquid while her nails assault my soft skin? In the time it took me to decide, I choked, while the milk kept on flowing down my throat. I coughed up everything I’d swallowed, sobbing, hiccuping, drooling, sinking into the endless tragedy that was my short life.

She slapped my back with greater force than was needed, but I felt in her tension the horror that had seized her: she had just understood that one day the baby elephant would arouse such hatred that she would break its skull against a wall in stupid delight, accepting the guilt of such a crime just to grant herself that momentary happiness.

She decided to call for reinforcements. She hired a young au pair who, despite being fairly hardy, could barely carry me, and who kept slipping out without asking for a break. Then there came a long line of nannies who couldn’t bear more than a few weeks with me, sometimes even just a few days.

But I was rather likable. I think I would have been quite sensible if I hadn’t been so tormented by hunger. But the nannies had to get up in the middle of the night at the sound of my shrieks while my parents slept, shielded by earplugs. Each of the nannies came to see the allure of violence that my mother did, and made off before they did the unforgivable — which just goes to show how little maternal feeling counts for.

Finally, my mother found the best nanny possible: my father. Then she left.

My father. My savior. A smiling, charming genius. His eyes so bright with certainty that no ulterior motive could darken them. The fairy leaning over my cradle, the last in a long line of wizards.

The only one to see me as something other than a fat, misshapen lump.

The first time, as he came back from a trip that had kept him from being present at my disastrous birth and plunged into this abyss that had swallowed up my mother, he stood there as a divinity made just for me. He smiled.

He was the only one who did. He didn’t notice the excess fat that left me flabby and ungainly. He didn’t see the furrow of frustration that waiting for food had dug into the corners of my mouth. He paid no attention to my spasmodic hands reaching for some breast to latch on to, or to the incessant sucking motions of my lips.

He crouched down toward me, expressing his admiration and astonishment that such a royal being could have resulted from his union with his wife. My father is a creator. He sees only this aspect of me — a sort of masterpiece that he would now work to perfect. This smile and this exaltation surprised me so much that I momentarily stopped trying to eat.

Oh, she’s magnificent! he declared. My mother stared at him as if he were an alien. How dare he show such happiness, putting on that clownish grin that didn’t fool anyone? Didn’t he see that this baby wasn’t in fact one? She turned her head toward the wall and refused to reply. He lifted me up effortlessly, sure of his strength. This strength will be yours, he silently promised me. It’s yours to claim. He would never go back on this decision.

It’s not his fault if I carry a burden too heavy for me. And this burden will always darken the gold of his presence. Such goodness is impossible.

Then, mysteriously, he told my mother, We have two beautiful daughters. He instilled an awful suspicion within me: that of having devoured my sister in utero and of having come out both absolutely nourished and eternally famished.

My mother banged her head on the wall, clenching her teeth and her fists.

I think if she had turned around, she would have spit in his face. Her blood was boiling. Her torn belly tensed with the force of her rage. It may have been at that moment that she started to abandon us.

That’s where the lie of my dual life began, my impossible struggle to resolve myself.

Ever since this entrance into materiality, I have never stopped expanding. I overflowed every space where life tried to confine me. I’m limitless. I want to look the sky in the eyes and take pride in it. I’m dazzled by inordinateness.

And I grow. And I grow.