THE MOON

I’d never experienced virtual reality,

nor, I soon felt, had I ever experienced anything

so dazzling and hateful at once. The VR installation was called

To the Moon. It accommodated two

museum visitors at a time, and I’d made the appointment

so we could go together.

With my headset in place, the room was still there

but my body disappeared. The stool where Chris had sat beside me

was there, but Chris was gone. Then the room was gone

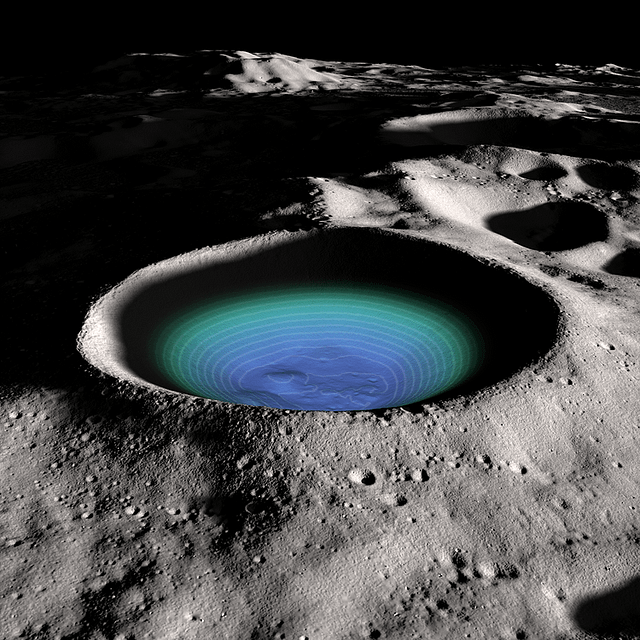

and I was alone on the moon. The feeling of transport was real

and the feeling of space —

But the attendant had promised flying — just extend your arms —

and it didn’t feel like flying. It felt, crushingly, like I was missing out

on a major part of the moon experience.

There were ghostly dinosaurs on the moon,

there was a giant solitary rose made out of moon rock and a donkey

that I rode along the surface of the moon.

I came to the edge of a crater and wanted to jump

but this was a passive section of the experience.

What did you see on the moon? I demanded as we left,

but Chris was experiencing nausea. He’d had a bad cold that week

so I’d been thinking about his death —

and now the aftershock

of my abandonment on the moon left me weeping.

What did you see on the moon? The attendant went in behind us

to wipe down the headsets, to welcome the next guests. I was angry

because this all felt like a vision of the future.

But maybe that’s how people felt

when we landed on the moon.

Chris and I had both been granted residencies at the museum

for our writing, impossible luck,

and over the days had freely walked

through galleries that required no appointment.

But with Chris’s illness, we’d been sleeping

in separate rooms, then going to our separate studios,

and now our separate moons — Chris flying and swooping

so dramatically you could vomit, while I stayed down on the ground.

That’s how it was, sometimes, living with another poet.

Like we could both put on headsets and wave the controllers —

arms outstretched and triggers depressed — but for me alone

nothing happened. People say that poets love the moon,

but I got into poetry because I liked words and small things

and lacked the imagination for fiction.

There’s a book my dad would read us

about a princess who falls ill and won’t be well until they bring the moon,

it’s hopeless! But then someone asks

what she thinks the moon might be:

a disc of gold, no bigger than her thumbnail.

So, then, quite achievable.

But what will happen when, moon in hand, she sees the moon

still in the sky? It’s fine — in her cosmology,

the moon grows back like a tooth. The book is called Many Moons.

Outside my studio window, dirty snow is piled up

around a pool of ice. When I arrived, it was liquid,

but it will be an ice rink soon —

I’ve seen them work, they hose it down to smooth it.

Now it’s night. Two men climb into cars on either side, their headlights

meet across the ice. Now two visitors approach on foot.

Tenderly, and not with their full weight — with one foot each — they test the ice.

The moon is far away for all to see. I’m imagining the poems Chris will write.

NEW YORK

Arizona was the first dance made by Robert Morris, 1963 at Judson Memorial Church. The dance was twenty minutes long, in four sections, accompanied in part by a recording of the artist reading his text “A Method for Sorting Cows.” Two men are required to sort cows in the method presented here. It was a solo performance.

For the second section, Morris stood at center stage beside a T-like form, which he repeatedly adjusted and retreated from. A lampstand, two sticks. Morris had developed an interest in dance having married the dancer Simone Forti.

(He later left the field at the behest of dancer Yvonne Rainer.)

In 1961 or 2 (sources vary), he’d staged a performance, part of an evening organized by La Monte Young at the Living Theatre. A sculpture he’d built — a plywood rectangular column, Column — “performed” a choreography. For three and a half minutes, it stood upright, then it toppled and lay on stage for another three and a half. Morris, in the wings, knocked the column over by pulling an invisible string. Initially, the idea had been for him to stand inside the column and effectuate the fall, but rehearsing the maneuver in Yoko Ono’s loft, he’d gashed his eyebrow and ended up in the ER.

Forti had put on a program in that same loft in ’61, involving movement, objects, and rules. For one piece, in which Morris participated with artist Robert Huot, she’d installed two heavy screw eyes in the wall. Morris was instructed to lie on the floor and stay there at all costs; Huot, given an eight-foot rope, was instructed to tie him to the wall.

In New York, I’d had an affair with a man who volunteered at the Dream House, the sound and light environment created by La Monte Young and his wife, Marian Zazeela. Basically, Young designed the droning sound and Zazeela the magenta light. It was installed in a loft downtown. The man I knew was in charge of asking visitors to remove their shoes, and watched over their stuff while they were inside. When I went to see him there, I realized how much his own apartment — which he kept dim, with colored bulbs, and where he played obscure records — was inspired by this place. I did feel, in his apartment, like I was in an altered state. A couple times, I cat-sat for him, and the place was mine. He never saw where I lived.

Because we mostly met for sex, and because his apartment was small, and mostly bed, it felt, sometimes, like a stage for sex. Also, the sex was more prop-based than I was accustomed to — ropes and gags. I stayed naked, and he drew me baths and adored my flesh and I barely talked and felt like a cat, or a five-foot tower of fruit.

The critic Michael Fried, in his essay “Art and Objecthood” in Artforum, dismissed the “literalist” sculptures of Robert Morris and Donald Judd as “fundamentally theatrical.” He quotes from Morris’s own Artforum essay “Notes on Sculpture”:

One’s awareness of oneself existing in the same space as the work is stronger than in previous work, with its many internal relationships. One is more aware than before that he himself is establishing relationships as he apprehends the object from various positions and under varying conditions of light and spatial context.

Fried takes this and argues that literalist art, like theater, exists for an audience. You might say the art is activated by the beholder, who encounters — within this staged environment, under these lights, etc. — a situation. But what Morris describes isn’t viewer as audience. Both viewer and object are dancers.

NEW YORK

After he moved to Seattle,

I couldn’t get any other man

to do it right.

No, not like you’re mad at me.

THE MOON

Bausch had her dancers create movements

to express ideas, experiences.

“The moon?” I depicted the word with my body

so she could see and feel it.

For Vollmond, a giant chunk

of rock evokes a lunar landscape.

Water fills a wide, shallow trough in the stage,

reflecting the dancers’ movements.

Rain falls intermittently.

Dancers climb the rock. Dancers climb

other dancers. Rain falls and men with poles

sort of row themselves across the stage,

skate-sliding on the surface.

Now they swim-slide on their bellies

in the overflowing trough.

I watched this, finally, in Pina, the movie,

while Chris listened to something

in the other room.

Dancers wade into the trough,

scoop water up in buckets

and splash it on the giant rock,

like trying to save a whale.

They throw water on each other,

on themselves, their clothes are drenched.

The water stuff is primal. There are other

heterosexual antics, too, not in the film.

A man races against the clock to undo

a woman’s bra. Men pour liquid

from bottles from great heights,

overfilling women’s glasses.

Vollmond was one of Pina’s last works.

Of the performances after her death, critics expressed

a certain weariness, alongside great esteem.

Nothing remains new.

She requested a gesture related to “joy” —

joy or the pleasure of moving.

From the movement I presented,

she created an entire scene.