Essay & Fiction Online

Escape from America

Sometime in the near future, Anton Hur decides to leave America for good.

By Anton Hur

He sends the text message to his husband, who is already on the other continent, and turns off his phone to prevent tracking: Home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.

It’s a line from a Robert Frost poem. He and his husband use it as a trigger code for what they call “the reverse-Miss Saigon scenario,” the one where his American husband must escape the country by reaching the roof of the Korean embassy in DC. The name is a joke, but the need to escape America isn’t. His husband fled and reached Korea a few weeks ago. Now it is his turn to run, figuratively, for the helicopter. He switches off the lights in their house for the last time, checks that the stove is off, and heads out the door.

He stopped telling the Miss Saigon joke months ago. His American acquaintances were becoming increasingly offended by it.

It wasn’t their offense that deterred him. He had never cowed to nationalists before and nationalism was not unique to America; in Korea, flocks of zealots could regularly be found waving flags in Gwanghwamun Plaza. But he was startled by the “increasing” part of it. Americans were becoming more and more defensive about being American, less and less likely to laugh off jokes about gerrymandering or their ridiculous institutions like the electoral college. They increasingly denied their genocidal history, their very real problems with the industrial prison complex and state-sanctioned violence against Black people and other non-whites. He had been in the middle of taking a midterm for a critical race theory class at a local community college, citing Audre Lorde from memory, when an administrator came in and told the proctor that the state was shutting down the course, effective immediately.

That was a year ago. The college itself has closed since then.

He would have to take the car because this country has no high-speed rail. Or universal healthcare. It doesn’t have a lot of things. The most developed nation in the world, behaving like it was still the “frontier.” The frontier of what?

It’s a beautiful country, possibly the most geographically beautiful country in the world. The deserts, mountains, lakes, rivers, amber waves of grain from sea to shining sea, all of that is true. He’s lived these past few years on some plain plains, but even here there’s desolate beauty and very, very clean air.

Passport, citizen’s registration card sewn into the lining of his jacket, open-carry license. But would it be enough?

There’s a rumor that martial law will be declared at sundown. He has to make it to his flight to DC before then. Then on to Korea.

“So,” the gun salesman had said looking him up and down, “you ever fired a gun before?”

He was a Korean man, of course he had fired a gun before.

He had also thrown live grenades, crawled under barbed wire in the mud, slept three soldiers to a tent in the freezing cold, and done a thousand roundhouse kicks in formation. Those were just the bare basics taught to any healthy Korean man, all of whom were obligated by law to serve in the military.

None of that had disappeared just because he married an American.

They first met in Seoul.

He had no desire to date a foreigner. There was a word for Koreans who dated foreigners, and he was not that. (It later amused him that American gays had a term for Asians who dated Asians, but not for Asians who dated non-Asians, because the latter was considered “normal.”) Americans were nice enough as individuals, but the politics exhausted him. The very mention of “dating an American” brought to mind sad, old, entitled white men who expected Asian men to flatter them. He pretended not to speak English around such people.

His husband is not sad, old, entitled, or white, though friends and family expected him to be.

Maybe there is nothing wrong with being sad, old, or white. But entitled?

He counts his cartridges and zips them into the inner compartment of his carry-on. He’s the one who should be entitled. He deserves to be the center.

The car.

It’s the car that’s the real challenge. Driving still felt unfamiliar to him. He had lived in Seoul for twenty years. You only need a car in Seoul if you have mobility issues or children, and he had had neither.

Then his husband accepted a job in America and proposed they move back. History is like a pendulum, he recalled his husband saying. America will start swaying back towards good once we’re settled there. At least I can’t imagine things getting much worse.

I can’t give up universal healthcare. I’m not applying for American citizenship if I can’t get comparable coverage.

All right.

And if they even threaten to take away my green card like they’re doing with Muslims and South Americans right now, I’m coming straight back to Korea and you have to come back with me, job or no job.

Deal.

And I’m not going to drive more than half an hour anywhere.

Uh . . .

He starts the car.

As he drives onto the deserted rural roads, he tries to remember the good things about America and what he’ll miss if he escapes.

It’s pretty here.

The produce is fresh.

The radio, when it isn’t being used as an emergency broadcast system, plays good American music.

His husband grew up here. (Well, not here, as he keeps emphasizing.)

It was peaceful in the Beforetimes, whenever you happen to draw that line: 2001, 2008, 2016, 2020, 2022, 2024. 1492.

He thinks. He thinks desperately.

Ah. They let him marry his husband here. And once he was married to an American, they welcomed him as a resident. How to reconcile this America with the America that would have rejected him if he was alone? Korea may have refused to recognize their union, but at least his husband was still able to obtain residency and a work permit. Americans are welcome in the American client-state of South Korea. For better or worse.

Once again, he congratulates himself for successfully convincing his husband to spend his sabbatical in Korea during an election year. What cleverness, what prescience! At least he had managed to get his husband out in time.

I’m a Korean citizen, he had said. They have to let me out of here and Korea has to take me in. So, you go ahead and I’ll tie up our loose ends here. We don’t want to look like we’re fleeing the country.

If all else fails, at least his husband will be safe. Stateless, but physically safe.

Dutifully, he stops at a stop sign.

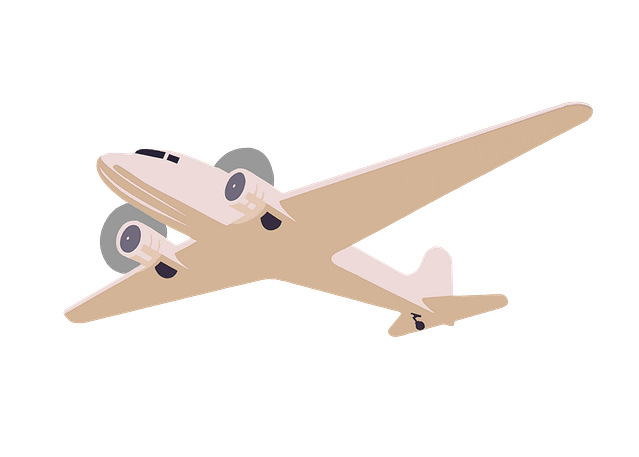

There’s an airport eighty-four miles from here but when he checked his phone that morning, all the flights had been canceled. He is on his way to the larger airport 150 miles away.

A hundred and fifty miles. How far is that? How many kilometers?

He was never going to get used to the imperial system now.

He had committed the route to memory, anticipating that he would need to turn off his phone.

Nevertheless, a lurking police car pulls him over.

This situation is impossible. He was driving slightly under the speed limit because this is precisely the scenario he was trying to avoid. But of course, no cop needs a valid excuse for anything, especially now.

What if the cop decides to search his car? Uncovering the gun under his seat, the ammo, the packed bags in the trunk?

But he has one other weapon: a perfectly flat, perfectly crystalline American accent. He will orally dot every “i” and cross every “t” in his overcorrect vernacular that East Coasters think is West Coast and West Coasters think is East Coast. If he can never be accepted as a local, he can at least try to be accepted as an American.

“Good afternoon, officer. What seems to be the problem?”

“You were driving too slowly. Your license and registration?”

He was not driving too slowly. But he complies, willing himself to be calm.

“Where are you headed to?”

In Korea, he has the right to not answer this question, and he probably has that right in America as well, but lately due process was being ignored.

“Springfield,” he answers truthfully.

“What’s your business there?”

None of yours, dick. “I’m visiting a friend.”

“You do know the president may declare martial law tonight?”

“That’s why I’m going to see my friend now, to make sure they’re safe. I’m going to drive right back.”

He has the name of the friend ready, their address, their phone number. The friend is a real person and a real friend, someone who has already agreed to corroborate his story if the police ever called. This friend is white.

Good luck, the friend had said. I hope you make it back home.

“You’re driving without navigation?”

Jesus. “I don’t need it, I’ve made this trip many times. They’re a good friend.” Damn it. “I mean, she’s a good friend.”

Too late, he realizes that “correcting” himself makes him even more suspicious.

The cop, inscrutable behind his dark glasses, seems to be weighing the situation in front of him.

Just as he’s about to speak, cop-gibberish issues from his radio.

Immediately, the cop tosses the license and registration into the car, runs back to his cruiser, and drives off.

Shaking, he pulls back onto the road.

The sun is about to set. It is bleak and wintry, not dazzlingly yellow and orange, despite it being late spring. This new season should be ushering in a new world, but instead it’s only the old one, drained of its power and beauty—the radio is warning of an unseasonal snowstorm later that night. All planes would be grounded, possibly for days. He has to make it to Springfield. It is do or die. He wants to throw up, but he grips the steering wheel and wills himself to calm down.

Some miles down the road, he is overtaken by a car being chased by a fleet of police vehicles.

He shifts to the side to let them pass, emergency lights blinking.

They go by too quickly for him to determine whether the cop who stopped him is among them.

He opens the window and throws up.

The road is empty again when he veers into the exit for the airport.

“Do you have a carry-on?”

He does not. He left everything in the car—guns, ammo, the bags he packed so carefully the night before. His personal item, a backpack, is mostly filled with clothes, but even those he has now decided to throw away once the plane lands in DC. He doesn’t want to bring anything from this tainted old life into the new one.

“Enjoy your flight.”

He holds his breath until the plane is finally in the air.

As soon as the chartered Korean Air flight from DC leaves American airspace, the American president declares martial law. He has made it in the nick of time.

Still, he worries if he looks out the window, he will see fighter planes trying to gun them down over the Pacific Ocean.

Incheon International Airport. As soon as he scans his passport, the gates slide open and welcome him into the Republic of Korea.

His husband is standing at arrivals, holding up a sign. It doesn’t say his name. Instead, it says, in English, WELCOME HOME.