I left my native country at sixteen, clutching at the first opportunity to escape. The Netherlands, I felt certain, couldn’t be home. I grew up in a small town where I felt all eyes were on me; I was queer and possessed of a book-won vocabulary that alienated my peers and was met with open hostility. I need to get out — out of Holland, where I’m rotting away. I accepted funding from the Dutch government to study literature in Cologne, Germany. Several years later, I moved to Scotland, then Hungary, then England.

I was too young, however, to realize that I would one day long to understand the Netherlands. That I would keep worrying at my unbelonging like a loose tooth. this country in which i / did not lay down my love. A few years into my self-imposed exile, I asked my mother for Dutch poetry, because poetry has always seemed like the best way to approach a sensitive subject: sideways, piecemeal, like reading coffee grounds and finding patterns in the negative space. She introduced me to the poet Hans Lodeizen, gifting me a copy of his collected works. I was surprised to feel an instant kinship with the voice that spoke to me from the pages.

Hans Lodeizen was a frail and lonesome child, if enveloped by class privilege. Born in 1924, he grew up in the affluent seaside suburb of Wassenaar, outside The Hague. His family more or less escaped the dark pall of economic devastation and Nazism, and his father, a teacher turned self-made businessman, created an elegant, rarefied home environment filled with art, literature, and classical music. Lodeizen’s troubles were more local and interpersonal: He suffered from asthma and so often missed school. He had a hard time relating to other children. His greatest friends were some of his teachers, and the ants whose universe he spent many hours scrutinizing in the backyard.

In high school, he became a jester and teller of tall tales, a reader of Nietzsche, a dabbler in astrology and palmistry. Perhaps his interest in divination was a first attempt to tap into a more profound strand of reality, but it also gave him a role to hide behind. In middle school, I’d done something similar: I managed to parlay my interest in witchcraft into the role of fortune teller, laying tarot cards with shaking hands for pretty older girls with sullen boyfriends. I remember the heady rush of being seen as an arbiter of fate — and the relief of having neatly sidestepped the social order (I knew I could neither have nor be that sullen boyfriend). Hans was struggling with his gay identity, too. He’d read the Swiss entomologist and psychiatrist Auguste-Henri Forel’s articles about ants, which had led him to Forel’s book The Sexual Question in which — in keeping with the prevailing opinion of the time — homosexuality was labeled a perversion. He’d been aware of his attraction to men for a while and despaired of ever finding a place in society.

So, like me, Hans longed for escape, albeit also driven by the unique political and economic context of his time — many Dutch teenagers during and after World War II felt devoid of future prospects in a country that had been brought to its knees. In any case, Hans became increasingly fixated on moving abroad to forge a new path for himself. International travel was extremely difficult but, through a combination of talent, luck, and leveraging his father’s connections, he managed first a brief stint in London, procuring insect-mounting pins for the Dutch National Museum of Natural History, and then secured a place at Amherst College in Massachusetts. In September 1946, at age twenty-one, he boarded a Holland-America Line steamship headed across the Atlantic. The company’s first passenger sailing since the war had been just four months prior. In Holland, he’d lacked the entry qualifications for even a bachelor’s in biology, but in America confusion about degree equivalencies suddenly got him straight into a master’s program. He’d managed to slip through a keyhole opening into a new life.

It was in the U.S. that he would begin to build an artist’s life, even if, academically, he floundered. At Amherst he found kinship with the poet James Merrill, who was instantly captivated by Hans Lodeizen’s “blue sunbeam eye” and vibrant mind: “Next to mine, Hans’s mental furnishings were streamlined, eclectic… In the biology lab he showed me the scarlet pulse of a fertilized egg. He wanted me to read Chamfort’s maxims, look at a mask from the Congo, hear the violin sonatas of Beethoven,” he wrote in his 1993 memoir, A Different Person. He was stung when Hans fell in unrequited love with their mutual friend, the handsome, masculine Seldon James. But Merrill’s initial infatuation gave way to an enduring friendship.

Roaming the U.S. in the breaks between his studies, too, proved transformative for Hans. In the summer of 1947, he drove cross-country to Los Angeles with a group of friends. In his journal he recorded his first sexual experience with another man in Hollywood. “His name? I forget.” The following spring, he hitchhiked to New Orleans, where he had several encounters with men and fell headlong for Hugh Wellington LaVigne, a student he met in a park. It was a watershed moment: in the months that followed he began writing poetry prolifically, suddenly releasing his distinctive voice.

Hans Lodeizen’s poems are ethereal, delicate things, often short, often all-lowercase, always in free verse. They combine frank, diaristic introspection — i’m so opposed to life / that i could cry and cry all the livelong day — with enchanted imagery that feels summoned from the world of dreams: i will roam the world on silver / feet like a hunter in daytime. They are populated with boats, birdsong, palaces, nighttime clearings, fruit trees, melon-slice moons. If they were a color, they’d be the vibrant chlorophyll of summer leaves.

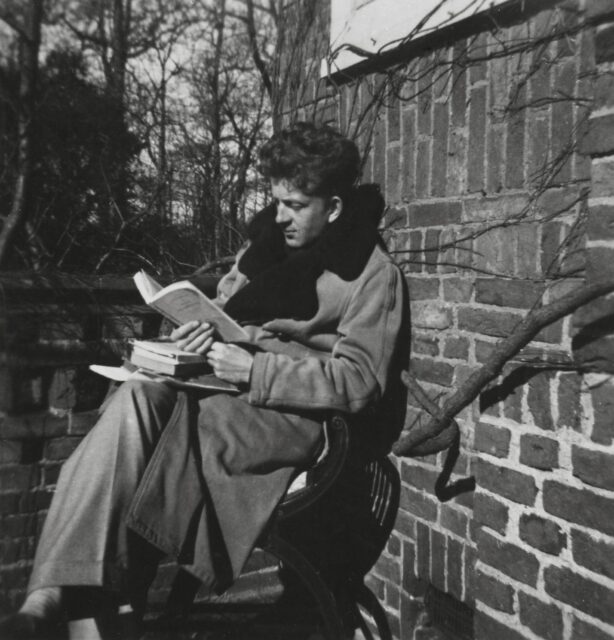

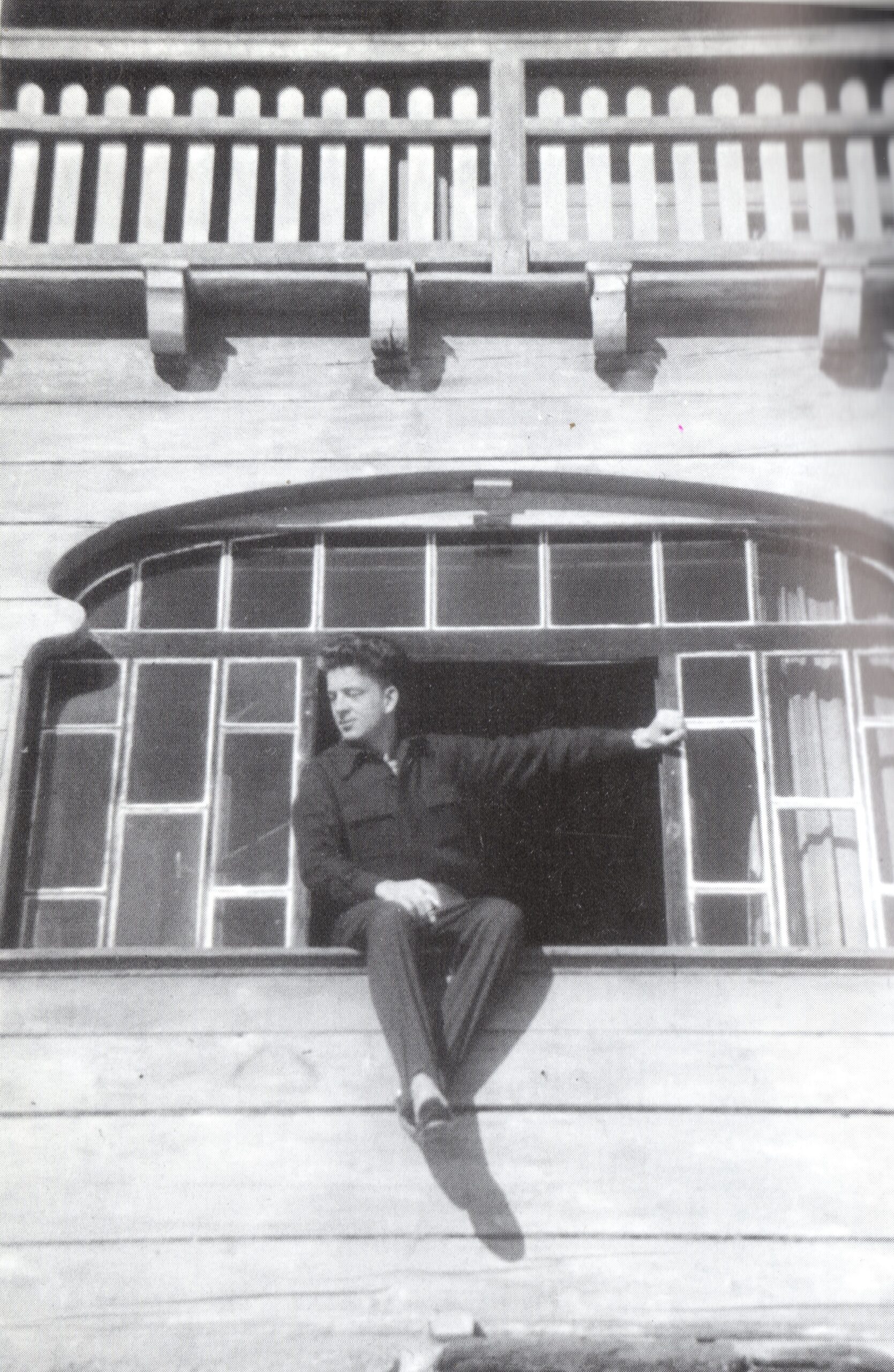

Poring over his collected volume for the first time, I found a home in his otherworldly poems, rich with portent yet featherlight. life flaps its wings / like an eagle above my altar and from the / shadows i divine / what will be. The thoughtful young man on the cover was handsome in a debonair, Kennedy sort of way, his light eyes trained on a distant horizon. And his words echoed this portrait: someone hungry for new experiences but interested, above all else, in cultivating his own imagination, setting the parameters for his life in a series of gentle assertions: I will never do a lot of work, but I’ll never / sully the world.

This resonated with me as a young person unsure of how to make a life that would nourish my mind rather than flatten it. From stuffy-yet-frantic academia, to waitressing, to corporate temping, to being bled dry in the arts — every option seemed designed to erode me. In Lodeizen’s defiantly intangible ambitions — I will take the wind into my arms — I read an elegant refusal. He often referred to the Netherlands scathingly, and I felt vindicated by that. He had a more favorable, if still ambivalent, view of the U.S. (the landscapes of both Amherst and the West Coast feature in his poetry), a country to which I thought I might one day belong. And he wrote frankly about desiring other men.

Poetry had barely featured in my Dutch high school education; I’d been discouraged by a stultified, withering canon of Pontificating Men that affirmed my sense that Holland had no room for me. My mother had been discouraged in just the same way as a schoolteacher, but she recalled Hans Lodeizen as a voice she liked. Now, he was speaking to me: a queer voice reaching through the ether, young, passionate, immediate, the polar opposite of the literary hetero-patriarchy that I’d been presented with in school — a totally different way of sounding and being in Dutch. It’s no exaggeration to say I probably wouldn’t have gotten into translation if it hadn’t been for him — here, at last, was Dutchness I could work with.

Scarcely knowing what I was doing, I translated some of his poems, which I sent in hand-stitched, palm-sized booklets to a few close friends. I also purchased a miniature voice box on eBay, the kind meant to go inside a teddy bear, and recorded my dad reading one of the translations, sounding as I imagined Hans would have: carefully enunciated English with a Dutch accent. I put the box inside a cardboard mockingbird I made — an apt emblem, I thought, for the endeavor of translation. The recording of the poem was followed by a brief clip of a mockingbird’s song. Having completed this project, I promptly put it away in a drawer and forgot all about it.

Sitting down to write this essay, I picture teenaged Hans, the hand-reader. I think of a blue-eyed boyfriend I had, three countries in, using the palm of his hand as a map of Manhattan as he walked me through his life. Signposts, auguries.

By the time I returned to Hans Lodeizen’s work — post mockingbird project — I was living in the U.S., my sixth country of residence. I was primarily revisiting him because he was Dutch in America, so I bought his biography by Koen Hilberdink. Years after having pieced together a rough outline from his poetry, I was struck by how it mirrored, even portended, my own life: a westward push across oceans ending, in my case, in Los Angeles, where I fell in love and stopped believing that being queer would condemn me to loneliness. Moving through countries, I’d shed layers of insecurity and internalized homophobia, becoming as light as a Lodeizen poem.

It moved me to picture this young Dutch man — seventy years before me, a full twenty years before the rise of the gay rights movement — falling in queer love in New Orleans and cruising in Central Park. Returning to his poetry, I saw a dreamscape animated by queer joy. I recognized the sheer tenacity of his affirmations: that breathless I will, I will, I will, culminating in the ability to say, in total defiance of his times, Who cares if I’m good or evil (…) I am in love / Without blushing.

Like his poems, his moments of contentment were brief, eked-out chinks in time. He had a love affair in New York with Julio Torres, a dancer from the Bronx, but academic failure forced him to return to the Netherlands. Shortly afterward, he was arrested for cruising in a public park — following World War II, there was a police crackdown on gay men in response to what was seen as a wartime loosening of morals. Likely as a result of his father’s connections, the charges were dropped, but it was a deeply humiliating episode in his life. He dreamt of escaping Holland again by becoming a diplomat. Since his reluctant homecoming, though, he’d been plagued by persistent fatigue and in 1950 he was diagnosed with leukemia. He died in a sanatorium in Switzerland at age twenty-six, just months after publishing his debut collection of poetry.

In the Netherlands, Hans Lodeizen has often been described as “a dreamer’s poet,” the patron saint of teenage turmoil. Perhaps this is why I moved away from him for a period — after the mockingbird, before the U.S. — favoring writers who I considered more socially conscious. But it’s easy to dismiss our teachers when we are done learning from them. From the luxury of the present, it’s easy for me to say: of course I would make a creative life for myself halfway across the world, of course I’d come to wear my bowler hat and my queer identity with panache, of course I’d eventually publish (better, revised versions of) those poem translations in a magazine. Of course I’d make my circuitous peace with my country eventually.

For a long time, however, those things weren’t evident at all. Looking at Hans Lodeizen’s work now, I’m impressed by how he managed to achieve so much in his short life — to seize a mode of life and artmaking so wholly his own with such confidence. He lived a joyful queer life and made a singular contribution to the Dutch literary landscape while standing outside it entirely. To me, he was a signpost, an augury, a gentle guiding spirit. In his poems I saw a keyhole opening into a new life, just big enough to slip through.

Hans Lodeizen. Courtesy of Van Oorschot.