A quiet, sometimes imperceptible bliss drips over Kudzanai-Violet Hwami’s paintings. In Eve on Psilocybin (2018), Eve is naked, grinning, and high on shrooms, but the artist’s representations of other highs are subtler. In You are killing my spirit (2021), the subject lies back on a bed, eyes closed, one arm almost reaching to the viewer, the other floating limply in the air.

You are killing my spirit, 2021. © Kudzanai-Violet Hwami. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

The legs are in a constructive rest—knees bent, falling into each other, feet flat on the bedding, hip width apart. Behind everything is a picture within a picture, encased by a pink trim: a number of obscured faces that seem to be gazing at the reposing figure with a certain madness. The faces are a limbo-like audience, half there, half not there, waiting and anticipating. But somehow these portraits avoid the feeling that these figures (who are Hwami’s family and friends or the artist herself) are being looked at. Through Hwami’s eye, the exchange is tender and unafraid.

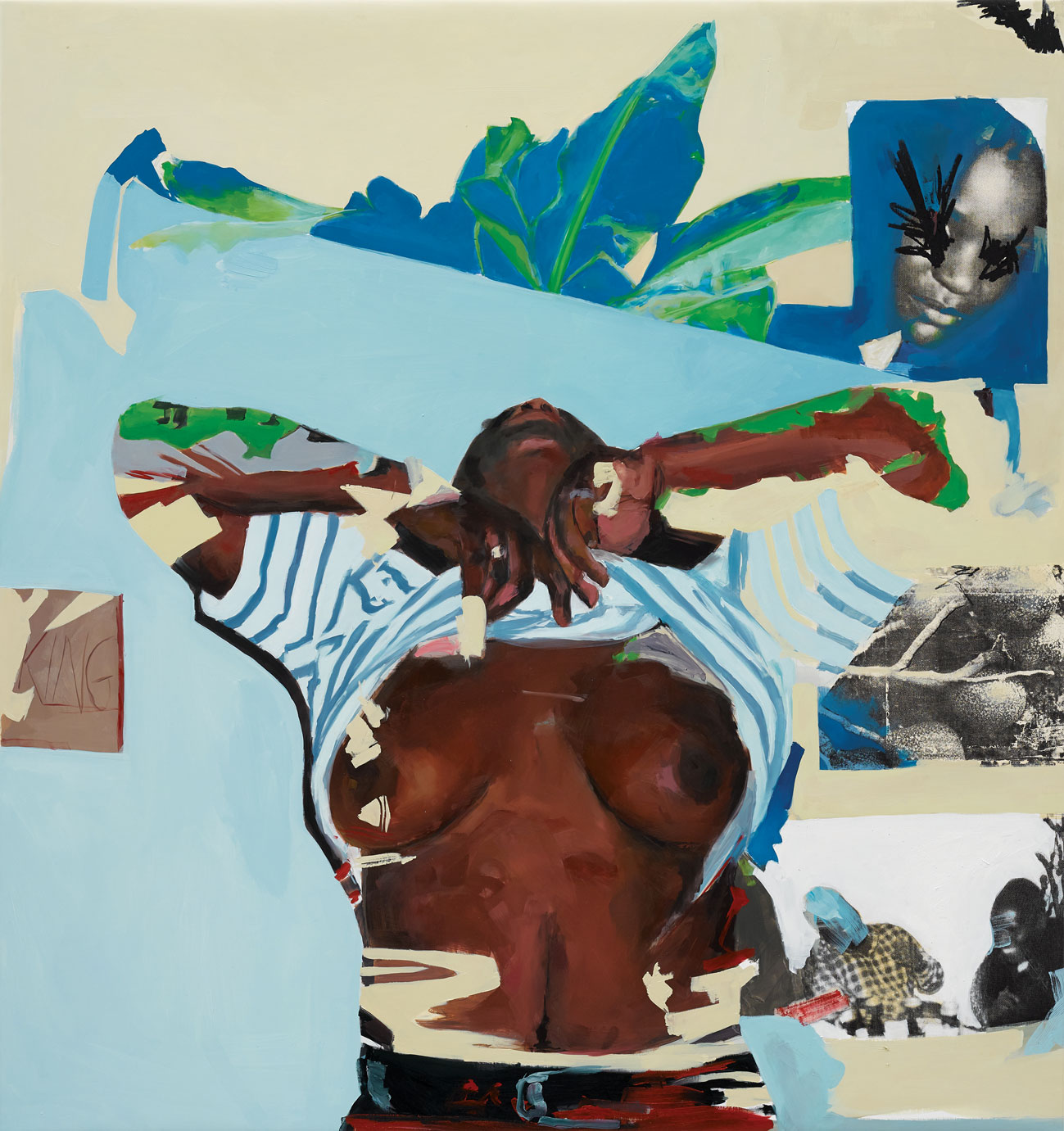

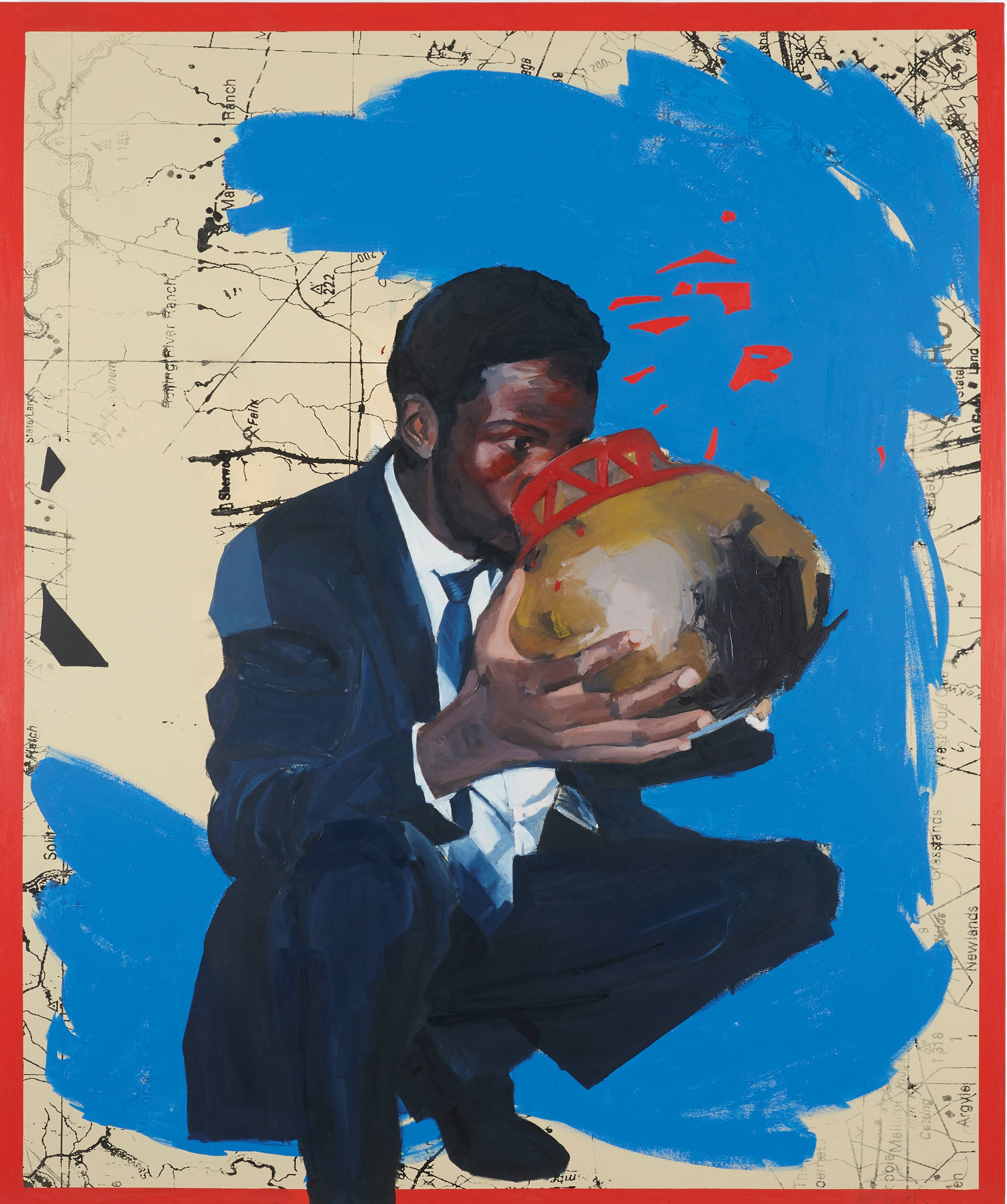

Expiation, 2021. © Kudzanai-Violet Hwami. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro.

Dance of Many Hands, 2017. © Kudzanai-Violet Hwami. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

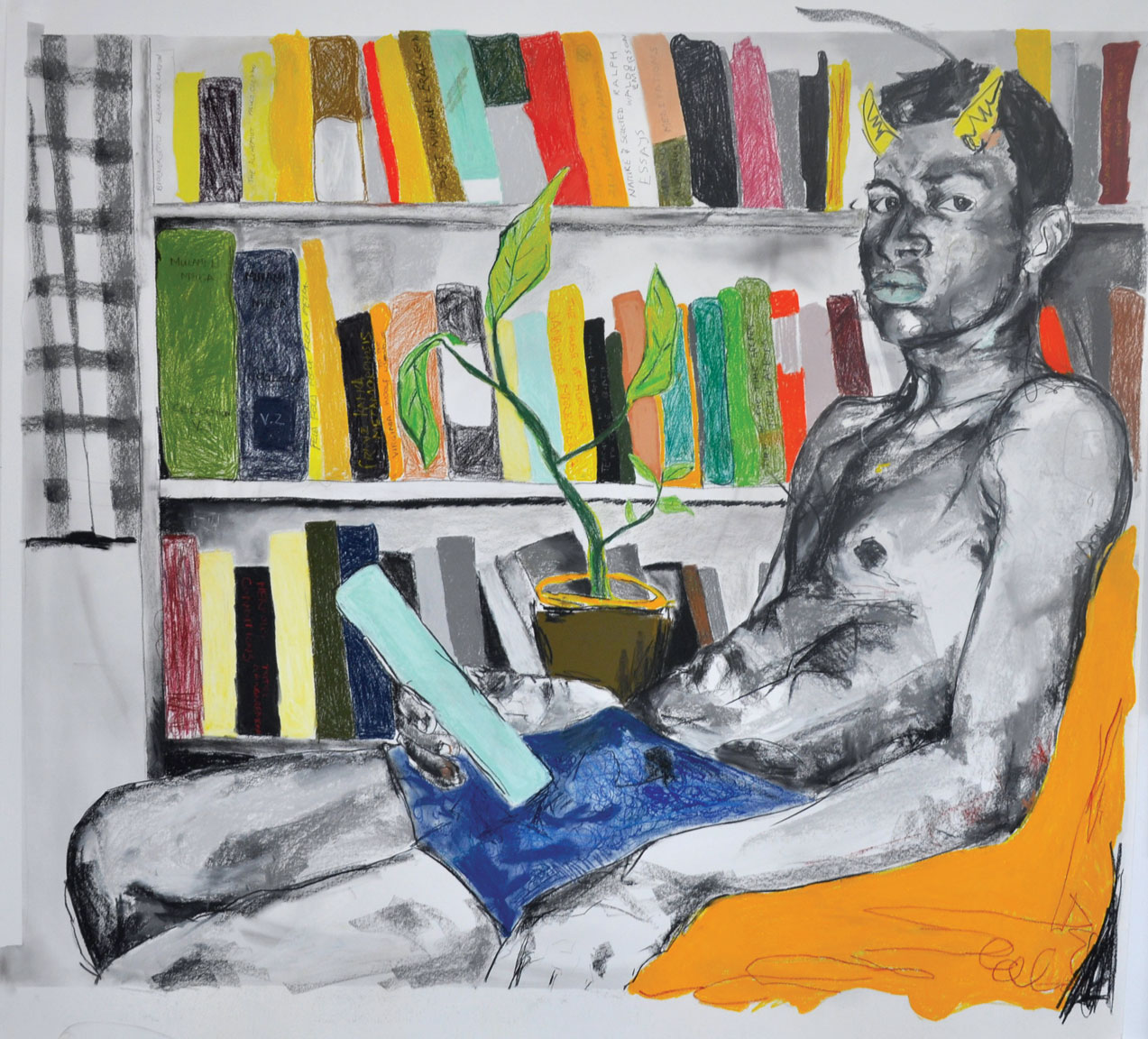

In the nudes Expiation (2021) and Dance of Many Hands (2017), Hwami manages a sexuality that is relaxed yet aware. It’s a sexuality that almost seems to lean back. In Mwana wa Mukami (2016), a person sits back comfortably against a reading chair with shelves of books in the background. The subject’s body is sketched out in gray, but most of the books are imaginatively colored: mulberry, marigold, forest green, turquoise, tangerine. Little yellow devilish horns, adorned with squiggly marks, protrude from a partially furrowed brow. Hwami is interested in introspection, but her work still exudes a jagged-edged playfulness.

Mwana wa Mukami, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Tyburn Gallery.

Hwami was born in Gutu, Zimbabwe, in 1993. She lived in South Africa until the age of seventeen, then moved to the UK, where she now lives and works. She has said of her trajectory, “With the collapsing of geography and time and space, no longer am I confined in a singular society but simultaneously I am experiencing Zimbabwe and South Africa and the UK, in my mind. I’m in the UK, but I carry those places with me everywhere I go.” This collapse is apparent in her aptitude for collage. She incorporates old family photographs, vintage porn, and archival images from the internet. The effect is counterintuitive, one of both stripping and layering. Photographs are typically used to cement truth and fact, but Hwami unwinds all that, celebrating the idea of subjectivity.

Bira, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Tyburn Gallery. Photo: Andy Keate

With Hwami’s artwork, interior life is a full-body high. The self grows crusty without the eye, trained to sense memories, shifts, analysis, feeling. Her paintings are evidence of small moments, big interventions. If you google Hwami, a bio will likely mention that she presented work at the Fifty-Eighth Venice Biennale in 2019 as part of the Zimbabwe Pavilion; she was the youngest artist ever to participate in the exhibition. But to claw at youth is a rigged game. Many of Hwami’s subjects—Black, African, queer, young enough—are prone to being seen, if they are seen at all, as simple, infantilized. Hwami, however, sees them as they are, and as they might see themselves.

— Tiana Reid