“Don’t stop until you recognize me.”

We do this every Sunday afternoon, as if our lives depended on it. Jordan strains his face like he has to pee but he’s holding it in. I watch him squirm and settle into a seated position on the floor. We’re performing a meditation technique I half read about in a magazine and half invented myself based on years of self-taught online Buddhist study. How it works is you take an object and focus on it until it’s no longer that object, but something else. It’s a form of unlearning that loosens up your mental associations and frees you from the attachments that no longer serve you. Depending on how advanced you are, you can turn something as ordinary as a toothbrush into a special healing wand or the sudden feeling of immense gratitude. I can do it with almost anything now. I can turn a stick of gum into a satisfying meal. I can look at Jordan’s face and see my soulmate.

“Okay,” he says.

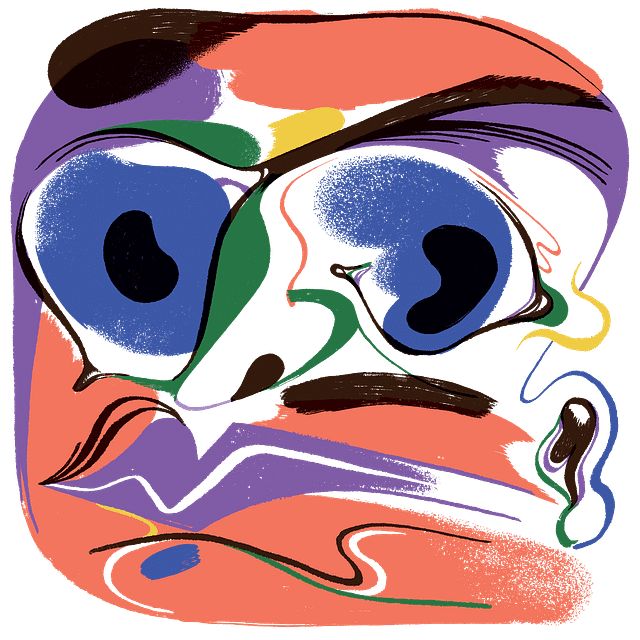

We conduct the exercise by sitting across from each other on the living room floor. I like to break him up into parts and slowly work my way up to his whole being. It’s like looking at a Magic Eye—revealing a depth that appears only when you’re paying attention. I bet he takes me in all at once, the way he does with everything: how he inhales food like a hungry stoner, or in bed, the way he yanks my underwear to the side and jams himself in. There’s no right way to do it other than sitting and staring until it’s over. Meaning, we’ve found each other again. Sometimes he sees me immediately and has to sit and wait until I’m ready. The longest we ever went was around two hours but that’s because I got bangs and he was having a hard time finding me under them.

I begin with his lips. They are thin, bright pink, and chapped, and I can tell they’re hiding something. I squint until all of his other features blur and disappear and then I attempt to communicate with his mouth telepathically. After twenty seconds, the disembodied mouth starts laughing uncontrollably, excited by its newfound emancipation from the face. I remain calm and try to ask it things like, “Do you love me or are you just afraid to die alone?” and, “Why won’t you let me touch your asshole?” But it’s too distracted to answer. It quickly grows confident, repeating “cunt” and “motherfucker” over and over again, like a tic. I realize the mouth on its own has nothing to tell me, and place it back onto the face with a firm blink.

A strobe of afternoon light cuts through the window, illuminating thousands of dust particles descending upon our jute rug. I swallow a cough and wonder how much dust I’ve eaten in my lifetime. Several pounds, at least. The microscopic film coats every surface of our modest apartment, the one we’ve shared for the past six years and never thought to leave because rent in the neighborhood has doubled in the past two years alone. Just like that, our apartment has become highly coveted real estate. I think about this whenever I hear the elderly widow above us farting loudly in her kitchen or screaming Slavic insults into her telephone. Pizda materina! “This is heaven. I’m in heaven,” I repeat to myself as I crush another silverfish with a giant wad of paper towel only to watch it crawl triumphantly out of the trash can, disfigured and limping. We’re royalty, in a sense, and even though we’ve done nothing to earn it, we agree that on a cosmic level, we have. Friends anxiously wait for us to leave: find a duplex in the suburbs and move on with our lives. What they don’t know is that we’ve agreed to grow old and die in this apartment together, no matter what.

Most couples never see it coming: that thing that blooms over years like mold, making them lazy and forgetful. It got so bad for our downstairs neighbor Geoffrey that he confused a woman he met online for his wife, Eleanor. He eventually moved in with this woman, claiming he was no longer convinced that Eleanor was who she said she was. Well, she was. I saw her yesterday. How do you just forget a person like that?

Some days I can see him so clearly, my husband, but then he shape-shifts into a child with a fever, or a slob roommate, or a chatty girlfriend. Or worse: an appendage of mine, some human-shaped growth with hair and teeth that spooks me every time it brushes against my leg in bed. We even have our own language: a garbled baby talk that doesn’t so much communicate meaning but evokes a general mood. Pleebo, Boobkus, Moosh, and so forth. We are like two wounded children. My therapist calls it “enmeshment.” It’s embarrassing, but I can’t stop.

Jordan never cared much for meditating but is willing to try anything to save our marriage. Maybe save isn’t the right word for it, rather: sustain, nourish, grow. “Safe words,” he jokes. He’s an obedient partner and agrees with me on nearly every topic except when it comes to my body, which he worships despite its obvious and well-documented defects. Specifically, my most problematic areas: the cellulite under my ass, how when I lie on my back, my nothing little breasts disappear into my chest, the disappointing ways my skin betrays me despite a rich diet of retinoids and sunscreen. His defense always feels personal, as if I were offending someone who was not me—an orphan or some omnipotent god figure. I can’t trust that kind of confidence.

As a rule, we approach matters of the heart with caution. We both suffered the indignities of online dating after thirty and emerged too wounded to talk about what we’d seen, fixating instead on easier topics like the state of our gut flora or thoughtful ways to reduce our carbon footprint. Crawling, just barely, off the battlefields of our twenties, we were embarrassingly ill-equipped for the bigness of love. The brutal heft of it. I couldn’t bear it, not for a lifetime. I need a careful love, a reliable witness. No one says this out loud, they just know it. You get tired of chasing the ghost and then you trust fall into the arms of whoever will catch you. It’s a survival skill, a way to eliminate risk. I told Jordan my entire sexual history on our first date, hoping that he’d find my display of forced intimacy endearing, and not manipulative, as a former therapist once labeled it. Still, it took him years to reveal that his previous and only girlfriend left him for a female lifeguard, forcing him to reconfigure his jealousy to include both men and women. He avoids public pools now, says the smell of chlorine gives him a headache. It’s an unwanted feeling, like a fear of dogs after an unprovoked attack by the family pet.

Ours is an uncomplicated love, aside from the occasional flare-up we offer each other: an email from Jordan’s ex-girlfriend asking for her copy of The Artist’s Way back, or a recurring sex dream about a cousin that haunts me for weeks. Despite our precautions, we started losing each other under layers of performance fleece and reruns of British procedurals. Our sex, too, is predictable and choreographed. I could do it with my eyes closed and often will. I like imagining other people on top of me, like his father, so that I could be the one to give birth to Jordan and raise him to be more self-assured and independent. Less sensitive to criticism, also dairy.

When my mind wanders like this, I wiggle my toes to return to my body. I ground myself in space and time by relaxing my eyes to get a full view of the room without breaking my focus. The first thing I notice is an industrial steampunk-looking lamp that needs a special bulb I never got around to buying. I thought it was cool just a few months ago and now every time I look at it, I want to hurl it out the window. How could I have been so wrong? I usually have discerning taste but occasionally I surprise myself with an impulsive chevron print or something macramé and worry that I actually have no idea who I am or what I like. I strain my eyeballs to the edge of my peripheral vision, where a clock sits on a mantel, but it’s just a white orb with no numbers. How long has it been? I’m already bored, so bored, so bored.

The sound of Jordan shifting his weight brings me back and I unrelax my gaze and bring my focus back to him. Hello, hi. I’m here. I look down at his chest and notice he’s wearing my beige sweater. I like the way it drapes over his pointed shoulders. I like a thin man, almost sickly-looking. It makes him look so graceful, like a dancer. We share clothes, mostly neutral-colored cotton basics from Uniqlo; that way we don’t have to expend energy picking out what to wear in the morning. It’s more efficient since we both work from home. Jordan scores film and transitional music for reality TV and I work part-time for an environmental advocacy group. So while the planet cooks and world leaders threaten global annihilation, we’ve resigned ourselves to an indoor life, thoughtfully constructing our own private paradise in uncertain times.

Sometimes I worry we’ve done too good a job and we’ll never want to leave again. Our efforts to safeguard against loneliness made us too dependent on each other, causing a self-perpetuating loop. The more together we are, the more we shut out the world, the more we distrust it, the more we need each other, et cetera. I’m finding it harder and harder to go outside when everything I need is right here. Every room has been optimized for maximum efficiency and comfort: a black-and-white dish set, a single bread knife, a fake fig tree by the window, a tweed love seat and a glass coffee table and a closet filled with expensive Canadian wool blankets. We’re both inspired by Kanso and wabi-sabi design, but Jordan made me get rid of our bonsai tree out of a sensitivity toward cultural appropriation. At the start of every season, we like to reset by purging all of our nonessential belongings and surrounding ourselves with objects that evoke joy. The goal is to eventually want for nothing. The goal is to be free.

This controlled environment works for now, but what about the future? Who will we be? My future self is capable of anything and I hate her for that. I’ve heard stories about men who emerge from botched brain surgery as pedophiles, and no one knows why. Or those women who smother their husbands with pillows or sleepwalk into the ocean. When I shared my concerns with an online chat room for advanced meditators, a few of them suggested I incorporate the drug ecstasy into my practice to encourage deep feelings of empathy and connection with my partner. Jordan had never done it and the one time I did, I slow danced with a coatrack alone in a hotel room, sobbing. I remember it being cathartic. I eventually managed to procure some pills from my niece’s boyfriend Chad, but whatever he gave me must have been cut with amphetamines, because instead of meditating we took turns picking at the shower grit, scrubbing the walls, and wiping dust off the venetian blinds until there was nothing left to wipe. I stayed up all night listening to the sound of Jordan slapping his dry tongue against the roof of his mouth while I heard a symphony coming from inside my own brain. I’m worried I caused us permanent brain damage.

I look down at Jordan’s folded legs and try not to laugh; nothing is funny, but my restless body is filled with so much energy that it sometimes expresses itself without my consent. The sitting is so uncomfortable it’s impossible not to laugh or cry or hum a little tune. My body will do anything to cut through the silence. Jordan almost laughs but it dies in his throat, choked out by his enormous Adam’s apple. I immediately think of the saddest thing I can think of: Jordan as a toddler waving goodbye to his mother as she pulls out of the driveway and never comes back. His baby cheeks pressed up against the foggy glass. “Ma-ma!” he screams in an empty living room. This never happened, but it helps me to recalibrate. I return his gaze with renewed seriousness. I fix my eyes on his nose and wait for a revelation, some recognition of our truest selves, and by that I mean the best versions of ourselves: the ones that were advertised to us, promised to us in front of God and everyone we know. I think if we look hard enough and really focus, we can remember who those people are and how to coax them out. Maybe we’ll discover we’re sex positive or into vape culture; I’m open to all possibilities.

I stare into his eyes, which are wide and expressionless, like a curious toddler’s or a benevolent monk’s. His eyes are always watching me in a sort of all-loving, all-knowing kind of way. “You’ve got an eyelash,” he’ll say, “make a wish!” then present it to me on his finger, things like that. He has monitored my every move over the years—from the way I incorrectly lift an Amazon package (legs, not back!) to the irregularity of my menstrual cycle to the way I walk slow “on purpose”—as if he were taking notes for a research study on the most inept woman alive.

In retaliation, I take secret pleasure in making him cry. I’m not proud of this, but I’ve accumulated a greatest hits of insults that can make it happen on command. I’ll say things like, “You’ve told us this one already,” after he shares another depressing story about his dad’s beloved Jamaican hospice nurse to all of our friends over happy hour drinks. When he later tells me I hurt his feelings, I’ll roll my eyes and tell him to grow up, which makes no sense since he’s seven years older than me and has high cholesterol. I’ll mention that, too. I know it’s coming when he looks up at the ceiling to keep his tears from falling, hoping they might reabsorb back into his head. The look of anguish and betrayal on his face transforms him and he once again becomes a stranger to me. Immediately I fall at his feet and beg for forgiveness. My sweet Boobkus! Remember me? Making him cry for sport is both immensely pleasurable and physically unbearable. It’s the closest I’ve ever felt to being in love.

“Now?” he whispers.

I shake my head, no.

His face barely even looks human now, more like a mound of clay. I rub my eyes and look again. When I do, another man’s face appears, someone I’ve never met before. He looks as menacing as a serial killer or a lonely youth pastor. I start to worry that I’m hallucinating, that I’ve gone too far and lost my grip on reality. I believe this happens to advanced sitters, but because I’m a novice, it startles me. I look down at the ground and work my way back up again, hoping to snap out of it, but this time I see my college boyfriend Rico flexing his bicep and looking constipated. “Sup,” he proclaims. It’s just like Rico to show up like that, in a manner that feels forced and nonconsensual. I blink again and there’s Jordan looking back at me, totally oblivious.

Let me think: Jordan. Love of my life. I search inside the creases of his eyes, his defined jowl. I stare at the pink mole protruding from the side of his left nostril. Every time I look at it, I have a deep animal desire to rip it off. He looks panicked but hopeful, as if he fears being lost forever. I panic, too, but don’t show it. I’m determined to see him, really see him. Who am I looking for, anyway? I want the old Jordan, still perfect and unencumbered by my petty judgments. This was the same Jordan who had yet to discover my night terrors or my eczema or my student loan debt. The Jordan who inspired me to take up reading for maybe the first time in my life, just to impress him. Tolstoy? Yes, looove it. Him. Love him. The Jordan whose car seats and armpits and bath towels smelled like some heavenly combination of cologne and sweat; it gave me a drug-like high. It made me want to breathe until I passed out.

Suddenly, I hear what sounds like a synthy electronic beat playing through the vents and just like that, I remember the night we went dancing in a dark club, or rather I was dancing and he was sort of hovering over me, holding my hips, swaying awkwardly from side to side. We never go dancing, we aren’t those people, but we decided to try it one night after dinner, the way tourists might wander curiously into ornate cathedrals hoping to spontaneously feel the presence of God. “What if it’s fun?” he proposed, looking drunk and cross-eyed. Once we entered the club, we quickly realized that we were surrounded by sexy youths and professional dancers and our version of dancing wasn’t funny at all, it was humiliating. “I thought I was good!” I shouted. “But I’m actually bad!” He took my hand and twirled me to the tune of an imaginary polka beat as trap music thudded our rib cages.

“You’re the best one here!” he said. I fell into his arms and wept.

When I come to, he gives me a confused look, which I assume means that he’s lost me. I’m taking forever, and it reminds him of how slow I am at most things. I forgot that I’m also being watched and the realization horrifies me. Is my mascara doing that thing where it smears around my eyes and makes me look goth? Do I look too much like his mother now? Does he wish I looked more like her? What’s my hair doing? Did I even try to fix it? I feel exposed, as if all my flaws are on display at once, even the internal ones. I wonder if it shows on my face: My secret browser history. The contents of my manifestation journal. That ancestral rage in my blood that emerges randomly, like when we’re playing cards. Or how I’ve changed, seemingly overnight, and I don’t know how to stop. Can he see, too, that I’m trying? That I want to be good? I relax my face and perform a childlike smile.

The longer I sit, the less I recognize him. Even little things lose their context, a side effect of staring at anyone for too long. What are bodies? And what is a hand, anyway? Is it a hand, or is it a family of fingers? I imagine him dying in front of me. The hiss of his last breath, his lifeless body. It’s an old body, with spots and craters and pustules all over it. I’m afraid to touch it or go near it. I’m afraid of its coldness, its strange smell. I sit and wait and watch until he slowly comes back to life, filling up with blood, growing younger. I watch the spots disappear and he is himself again, breathing effortlessly.

I’m relieved, but I can’t unsee it: how it ends, right here in the living room.

The distance between us grows and grows until it becomes an ever-expanding, gaping canyon with exquisite vistas. Jordan is a dot, barely visible to the human eye. I sit on the edge of a cliff and wave violently in the hopes that he might see me. If I can’t find my way back, then what? What happens to two people separated by some abstract, unmeasurable distance? My Buddhist video tutorials taught me that meditation, or really any kind of intense, singular focus could cure anything: anxiety, food allergies, you name it. I briefly consider the possibility of being wrong.

The sun is setting. We hadn’t thought to turn on the light and it is getting dark, but neither of us can move. Moving doesn’t even seem like an option. The man in my living room scratches the tip of his nose. The problem is his nose isn’t where it’s supposed to be, it’s been grotesquely flipped and jumbled like a Cubist painting. His one eye hangs low on his left cheek and his ear floats above his head. It’s as if my brain had taken his individual features and scattered them at random. I sit waiting for the night to erase him in a sheet of darkness.

“You still there?” I ask.

“Yeah, are you?”

“Yep.”

“Can I turn the light on?” he asks.

“Please!”

Jordan gets up and flicks on the light switch while I rub my legs and come back into my body. Then he looks at me. “Well?” he says. “Did you see me?”

I never did. I saw him only once, on our first sitting. There it was: his soul. It happened so fast, like a shooting star or a head-on collision. Gone in a blink.

“Yeah,” I say, “I saw you.”

He smiles, then looks down and notices a giant brown beetle sauntering across our laminate tiles. It senses its being watched and freezes. Without saying a word, Jordan slowly picks up his slipper and crushes it with an impressive blow. When I get up to look, the beetle’s amputated antennae are still twitching and its iridescent shell has torn into bits of cellophane, covered in goo. I stand back and watch as he wipes up the guts with a paper towel and washes his hands meticulously, like a surgeon. I know I might never see him again, but I want to spend my whole life trying.