Sabrina Orah Mark’s monthly column, GROUND UP, is about the act of re-building when all seems lost.

When the inspector came to determine the cause of the fire, I led him around my charred house. “It was a little before 5AM,” I said, “when I heard a sound. Like a small hand crumpling up a piece of paper.” I had already told this story so many times. “I tried to go back to sleep, but the sound grew louder. I got out of bed and followed it to the bathroom and there were flames crackling up there.” I pointed to the exhaust fan. I should add something, I thought, so that he can imagine it. “The flames reminded me of brittle thorns,” I said. But they didn’t really remind me of brittle thorns. The fire reminded me of fire. And I didn’t even mean to say thorns. I meant horns. Like on a monster. The inspector thanked me and told me he’d probably be at the house for another hour or so.

I had been wearing the same thing for days. My hair was in a knot at the top of my head. It was December, and it was cold, and I was wearing flip flops, and I didn’t care.

“Is it okay if I take this for evidence?” asked the fire inspector. He had removed the exhaust fan from the crumbling ceiling and was carrying it under his arm. I was overcome with the urge to pet it, as if it were a frightened animal being taken away.

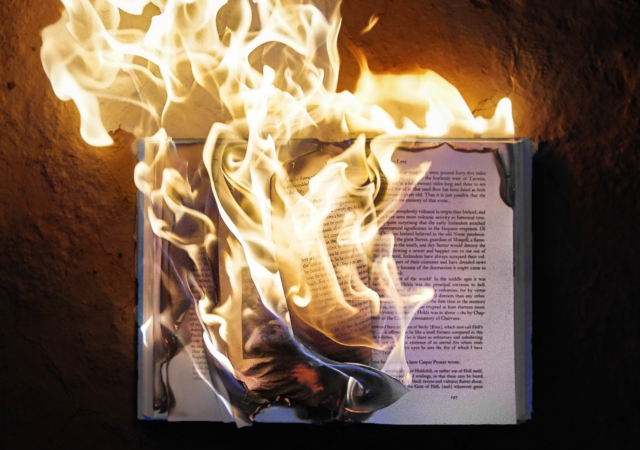

“Before you go can I show you something?” I started walking up the burnt stairs. “It’s up here,” I said. The fire inspector followed me. We entered what once was my office, and I pointed to a pile of ashes and glass lit by sunlight spilling through a hole in my house. “That used to be a bookcase of fairytales,” I say. “In that corner over there.”

I don’t know what I expected him to say, but he was the fire inspector, and he should at least say something. I think I wanted him to explain exactly how fire works, and exactly what temperature the fairy tales reached, and when did they crumple, and when did they vanish. Did the fairy tales suffer when they sprang from their bindings? Did they call out my name? I wanted his professional opinion. I wanted him to say this blows his mind as much as it blows mine.

I didn’t tell the fire inspector that for the last three years I had been writing monthly essays on fairytales. That they held me close when I was most lost. That I must’ve overused them, like rubbing sticks together, until they caught on fire.

The fire inspector wrote something down on his aluminum clipboard. It was one of those clipboards that was also a slim storage box. He tore off a sheet of paper, opened the box, and tucked the paper safely inside. Out of everything burnt and soaked in my house, the bookcase of fairy tales was the most unrecognizable. “Shouldn’t that mean something?” I asked. “Out of everything?” A piece of ceiling fell, way too close to us. “It’s okay,” said the fire inspector. But I wanted some big explanation for this disaster. I wanted destruction to come with a miracle. I wanted to know something now that I hadn’t known before. “Maybe it would help if we knew which piece of fairy tale burned first? The juniper tree, or the magic mirror, or the sleeve of a boy’s nettle coat? Or do you think we’ll never know because the smoke curled around the words, like mercy, so they couldn’t see each other as they all were disappearing?” “What?” asked the fire inspector. “I said I really like that clipboard,” I said. “I really should get a clipboard like that.”

The fire inspector determined the cause of the fire to be a bad exhaust fan wire. But I knew it was really from the fairy tales.

I read about a Kentucky woman who, during the 2022 Central Appalachia Floods, tied her children to her with the cut cord of a vacuum cleaner so if the water carried them away at least they would still be found together. They interviewed her on a swingset in the middle of a sunny field, which seemed like an act of cruelty. She was probably only thirty but she looked one thousand years old because she knew, like me, she was supposed to be dead.

“But you survived!” said one of the mothers who was also waiting to pick her kids up from school. “As far as I know,” I said. I felt around for my arms, like a joke. “Oh, dear,” she said. “You’re traumatized.” She looked away for a minute. “You should probably see a therapist.” I pushed my heal into the dirt like the Kentucky woman pushed her heel into the dirt, her arms around the rope of the swing, still hanging on. “Are you rebuilding?” the mother asked, cheerfully. “We are,” I said. “Does that seem insane,” I asked, “to rebuild?” “Well what are your other options?” she asked. “To run for the hills,” I said, “and leave only ruin behind.”

J.R.R. Tolkein defines the fairy tale as a story that depends not on “any definition or historical account of elf or fairy, but upon the nature of Faërie: the Perilous Realm itself, and the air that blows in that country.” If rebuilding a house on the exact same spot our house caught on fire, in a world on fire, isn’t laying foundation in the Perilous Realm, I don’t know what is. Maybe this seems at best grim, at worst stupid, but ruin wakes up astonishment, like fairytales wake up astonishment, and isn’t it out of astonishment that we rebuild, that we carry on at all?

“Just take the insurance money,” says my mother, “and pocket it. Rebuilding a house is a full-time job. Just pocket the money.” “Pocket it,” I say, “and live where?” “Pocket the money until you find your dream house.” “But what if my dream house is somewhere inside all these ashes.” “Don’t be an idiot,” says my mother.

“Faerie,” writes Tolkein, “is a perilous land, and in it are pitfalls for the unwary and dungeons for the overbold…The realm of fairy-story is wide and deep and high and filled with many things: all manner of beasts and birds are found there; shoreless seas and stars uncounted; beauty that is an enchantment, and an ever-present peril; both joy and sorrow as sharp as swords. In that realm a man may, perhaps, count himself fortunate to have wandered, but its very richness and strangeness tie the tongue of a traveller who would report them. And while he is there it is dangerous for him to ask too many questions, lest the gates should be shut and the keys be lost.” Did I ask too many questions? Did I stay for far too long? “The thing is,” said the fire inspector, “you don’t die from burning. You die from never waking up.”

For the first few months after the fire, my husband and I would come back to our rental with our arms full of broken things we picked off our burnt house, like fruit off a dead tree. It was exhausting work. We were like farmers, but instead of fresh harvest we grimly reaped what we still owned: Pens, two mezuzahs, a pair of scissors, a crumpled sheet of stamps, a laundry basket. One afternoon my husband dragged in a battered glass door from my grandmother’s antique bookcase. The one that kept my fairytales. “I can turn this into something,” he said. “What?” I said. “Something.” he said. I began to wonder, what even are things? And who are we when all our things are broken? And who are we when all our things are gone? The door now leans against the screened-in-porch of the rental house like the glass eye of a dead woman, an eye that will never close.

The insurance adjustor called. He disapproved a portion of our claim. Something we’d lost, he believed, had not been lost. It was just a question of us looking for it harder.

It has been nine months since the fire, and during that time I have purchased six lamps. Even though the unburnt house we are renting gets far more light than our burnt house ever did, I feel like I can’t see anything. “Are the lights even on?” I keep asking. “They’re on,” says my husband. I turn the switch on and off. On and off. A permanent mist. “Maybe we just need more wattage.” But the wattage is high. We can’t go any higher. What am I missing? What can’t I see? Am I awake?

There is a Japanese puffer fish whose colors are so dull he’s practically invisible. In order to attract a mate he digs perfect circles nonstop for a week, as the current tries to wash them away. When I first saw an image of those circles, I mistook it for a photo of some ancient amphitheater covered in blue sand. A place where a forgotten poet once read, in a great loud voice, a poem about the beauty of this earth. In the Perilous Realm, the fish builds circles with peaks and ridges, and decorates it with shells with the hope his mate will lay her eggs in its center where the sand is softest. We have already hired a man to rebuild our house. I give him the fish’s plans. I want a house exactly like that. One that disappears and reappears and disappears and reappears where it is most deep, where the light doesn’t reach. How much will that be? And how long will it take? We can wait forever. We are already one thousand years old.