We could all talk about love as a feeling. But what about love as a form? What does love look like as something you practice, something you have to work at, create a form for?

Sinéad O’Connor’s answer to this question is surprisingly sweet. Recently, at age fifty-four, she published a memoir, Rememberings. In interviews she’s noted, admirably frank, that she composed the second half of it under intensive psychiatric care. In 2021, she told the Guardian that she’d spent “most of” the last few years “in the nuthouse. I’ve been practically living there for six years.” Yet despite this, the book leaves its readers with a powerful sense of sweetness. O’Connor speaks of hard subjects, and as reputation suggests, she doesn’t hold back. She’s astute, fierce, funny, damning. She’ll tell you what she thinks of anyone, no matter how famous they are. But as the book progresses, you notice how many passages end in gratitude or praise. She’s glad for her relationships with the fathers of her children, even with the men she barely speaks to. She’s glad to have made this record, that song, and this one. She’s grateful for the hospital, the care she’s received (the book is dedicated, in part, to their staff and patients). She’s full of life and in praise of living — singing, mothering, desiring, healing, working — and this becomes her story, as she chooses to tell it, the form she’s found for herself.

This kind of sweetness — this complex gratitude — comes hard and goes easy. For the reader of O’Connor’s life story, it’s inspiring. It’s reassuring: that suffering and struggle and artistic ambition may come to this. But they don’t just come to this. You have to get there yourself. Love is a lonely business.

In the features, reviews, and interviews that responded to O’Connor’s 2021 memoir, a larger revisionist history was underway. In the wake of #MeToo, a sort of reclamation is going on variously for women of the ’90s and early 2000s (Britney Spears, Pamela Anderson, Monica Lewinsky, Anita Hill, Nicole Brown Simpson, Whitney Houston, and more). In movies, TV shows, and podcasts, there’s a drive to reclaim these women from the criticism and mockery they faced, to counter the forces that have shamed and underestimated and hated them.

The fact that this project is so belated — that these women, if they lived, already had to figure out, a long time ago, how to go on in the face of powerful people and institutions that ignored, exploited, abused, despised them — isn’t often emphasized. If it were, the newly retold histories of these women might feel less triumphal, more depressing. The loneliness of their endurance would be so obvious.

When we gloss over our own belatedness, we seem smug. This is progress. We get it now, these endeavors seem to say. Now we’re totally on Monica’s side. But that’s a story about you — how you’d like to see yourself — not a story about Monica. And I’m including myself here. I too return in shame to what I used to think about Monica, among others. I feel the need to correct myself, belatedly. I want to be part of something more just — part of a justice I can’t describe, since none of us have ever seen it.

To revisit the past from a comfortable distance, this time with a clear moral map — it’s reassuring. It feels good. We practice imagining ourselves on the right side of history. But then we’re practicing being on a side, when we need to practice being lonely.

For Sinéad O’Connor, the 2021 discussion focused on her famous protest in 1992. She may be better known now for that act than for her music. In October 1992, as you may know — it’s very well, if vaguely, known — she tore up a photograph of Pope John Paul II during her performance as the musical guest on Saturday Night Live. For years that was kind of all I knew about this act (in ’92, I was eleven). Then another phrase got attached to it: to protest child abuse in the Catholic Church. She’d sung, a cappella, Bob Marley’s “War,” a protest anthem against racism and colonialism, lyrics based on a speech Haile Selassie gave to the UN in 1963. But she altered the lyrics to place an emphasis on child abuse — she sang the phrase child abuse, with particular fierceness, in the middle of the song. In the US, the Boston Globe’s major stories on child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church would only start appearing in 2002, ten years after O’Connor’s act: when, as she reached the song’s concluding lines, which speak of “the victory of good over evil,” she held up the Pope’s image, obscuring her own face, then tore it in half, looking right into the camera as she tore the photo again and tossed it at the floor, saying simply, “fight the real enemy” (after which, in absolute silence, standing amid an arrangement of lit white candles, she removed her earpieces).

In the words of the New York Times, the protest “killed her career.” Scandal followed, birth of a pariah — for an artist who’d been, according to Spin, “a star on the same level as Madonna and Prince.” One week later, Joe Pesci hosted SNL and said that if he’d been there during her performance he’d have “given her such a smack.” This wasn’t the only threat of violence. She was banned from NBC. Commentary looking back on the incident often notes that because major coverage of child abuse in the Catholic Church hadn’t yet broken in the U.S., most viewers didn’t understand what she was talking about. Some thought the protest was about women’s rights. “In the popular cultural memory of the United States, O’Connor remains a crazy woman,” was PRI’s analysis in 2014.

In 2021, in contrast, media coverage around O’Connor’s memoir framed her as an authentic, independent, battle-weary woman artist who’s been long misunderstood. This didn’t feel like a redemption, twenty-nine years later. It felt like O’Connor’s explosive protest, softened by time, now overlaps with the kinds of political speech desired from pop artists — though these contemporary pop political statements tend to be slicker, clearer, more calculated, and minimally harm sales and careers. From a safe distance her lonely act can be repackaged as the new commodity.

In my youth O’Connor was talked about like she was crazy, like she was kind of cool and interesting, kind of laughable. Her ’92 stunt was described as a stunt, something big and weird someone did, something shocking, like the attention not the content was the point. A curiosity. Among teens she wasn’t necessarily hated, as she was by pundits and commentators at the time, but she wasn’t respected. She wasn’t treated like an authority on the subject she’d chosen, in a big way, to address. We knew how to watch the spectacle, but not how to listen.

So what happens if you listen?

In a brief video from 2005 — twelve years before the New York Times and the New Yorker began publishing accounts of serial rape, sexual harassment, and assault by prominent film producer Harvey Weinstein — a comedian hosting for Comedy Central stops Courtney Love for some playful chitchat on some red carpet. She asks Love (musician, actor, rock star, widow): “Do you have any advice for a young girl moving to Hollywood?”

“Ummm,” Love says. “I’ll get libeled if I say it. If Harvey Weinstein invites you to a private party in the Four Seasons, don’t go.”

She says it fast, as if tricking herself into not not saying it. She sounds like she’s giving you something. Twelve years or so later, when public favor had turned on Weinstein and criminal charges were forthcoming, Love stated that after this tiny interview aired, she’d been “eternally banned” by CAA, the major Hollywood agency — which worked with Weinstein on many films and, though at least eight agents had been told about his abuse, regularly sent young women actors to his notorious private meetings. Punishment for this undisciplined moment of truth.

I once watched a documentary in which Courtney Love’s own dad accused her of conspiring to murder her husband Kurt Cobain. Love is the sort of woman everyone feels comfortable saying anything about: messy, slutty, rambling, an addict, waste of talent, bad plastic surgery, whatever. Rumors shift credit for the songwriting of the band Hole away from Love and onto, traditionally, Cobain and/or Billy Corgan. These rumors can be dispelled just by listening to Hole.

Love’s speech that day was off-the-cuff, disregarded, prophetic. History proved its worth. For years Weinstein used highly repetitive strategies and scenarios, the hotel room setup especially. His crimes were both profoundly personal and systemic: by forcing and demanding sex “in exchange” for a successful career in the movies, and professionally punishing the women who distanced themselves from him, he set the terms for women working in American film.

But Love was not an authoritative speaker. In general — and especially when she suddenly broadcast this insider knowledge, ugly on a red carpet — she didn’t meet professional expectations. I don’t know if anyone ever took her good advice. Her accusation, not explicit but clear, had no effect on Weinstein’s status. It didn’t seem to inspire much curiosity or follow-up in journalism or among industry professionals — other than, like CAA, to punish the speaker — since twelve years and much more violence occurred before, from a more respectable realm of media, the story broke, or broke again, this time with the necessary authority.

But anyone could have just listened.

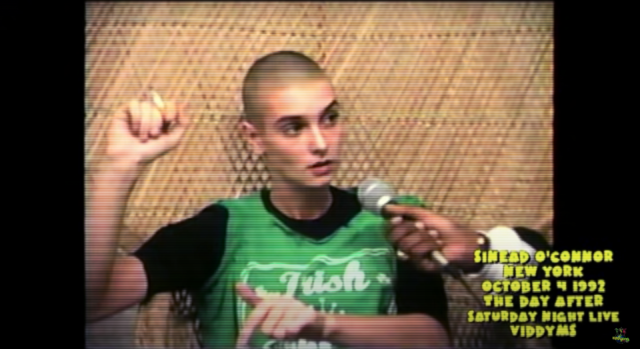

I just spent a year or two writing about Sinéad O’Connor. I’m forty years old, I’m part of culture. I got obsessed with something I found on YouTube: an interview O’Connor gave the day after her SNL appearance, on a reggae TV show called Viddyms. I can’t summarize what I love about this interview. What I love about it is that it’s not interested in summary and so is hard to summarize. Like poetry, as they say, it resists paraphrase. In response to challenging but attentive questions by host Tony Lindo, O’Connor speaks at length about the colonization of Ireland, legacies of trauma among colonized and impoverished peoples, addiction, the evil of child abuse, and how, in her view, the empire of Christianity (“the real enemy”) betrays the truth of God, God as truth.

So, you’ll have noticed, the common explanation of this incident still gets it wrong. O’Connor wasn’t protesting child abuse in the Catholic Church — the scandal as it would break through U.S. media in the next two decades — or rather she wasn’t just protesting that. She was protesting colonialism, which she sees as its cause. She was speaking from the heart of her sense of Irish history and identity. She was speaking from the heart of her experience as an abused child. A long statement she reads on this show begins simply: “My name is Sinéad O’Connor and I’m an Irish woman and I’m an abused child.”

In fact, in her SNL performance of “War,” she inserts language to protest child abuse at the exact point in the song where the original lyrics protested racist colonial regimes in 1960s Africa — illustrating her argument about this connection. But you’d have to already know the song (or Selassie’s speech) to catch this. Most people didn’t.

O’Connor made a global spectacle — lyrics altered; the Pope’s image, ripped, destroyed, dismissed, despised — that wasn’t clear. Not easy to grasp or assimilate or applaud. This gesture — so provocative — risked illegibility. And when she tried, in this expansive wide-ranging interview, for example, to explain, she risked unintelligibility. (“People are going to ask you, where are you getting your information?” Lindo interrupts her discussion of the relationship of child abuse to addiction to say.) O’Connor asked people to listen to something they didn’t already know how to hear, didn’t know how to understand, couldn’t just say what the summary would be. This kind of listening takes work.

She didn’t offer a slogan or a cause to donate to. She didn’t explain herself. She wanted to say what she wanted to say. If you wanted to know what that was, and why she said it, you’d have to get in there and interpret. You’d have to listen, then try to say something yourself.

If something can’t just be summarized, it’s still going. It’s still alive. A poem — you might say, if like me you’re often reading poems with groups of curious and skeptical people — is a technology that keeps working. Read it: it’s there for you, just for you, any time. It creates meaning in and among people, again, anew, every time.

No one clapped. O’Connor took out her earpieces and went on with her life. She got to find out what happened next. She’d saved the photograph of the Pope her mother kept pinned to the wall. She put it to work.

In Rememberings, she writes: “A lot of people say or think that tearing up the pope’s photo derailed my career. That’s not how I feel about it. I feel that having a number-one record derailed my career and my tearing the photo put me back on the right track.”

You may or may not watch the YouTube video I love (and it’s not short), in which O’Connor hunches over in a big rattan chair, wearing a green shirt that says Irish Princess and smoking, talking to Lindo about pop culture, protest, reggae, the Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire, colonialism and anti-colonial tactics. But I want to emphasize that it was just the two of them, talking to each other in a messy genuine uneasy thoughtful way. She’s clearly speaking as herself, not managed, not produced. She’s figuring out what to say by saying it. I don’t know if she thought her protest would be better understood or received than it was. As far as I can tell, that’s not something she talks about. She doesn’t seem concerned. She doesn’t need art to be clearer. It’s clear that she thinks her audience is able to listen and could understand her, get with her. She has faith in people. At some point in the ’92 Viddyms interview, she says that although they may be booing now, when they understand, they’ll be cheering. She’s not worried about whether she said the wrong thing. She’s worried about what happens if you don’t try to say something.

Her gesture was simple and swift, but it asked something real and hard from its audience. You couldn’t just hit retweet. You could threaten to smack or kill her, I guess.

I’d like to think that, if tomorrow, someone like Courtney Love said something serious like she said, I’d take her seriously. I’d listen. I’d like to think that, if someone undertook a protest that’s hard to support or to face — like Wynn Bruce’s suicidal protest this spring, an attempt to incite government action against climate crisis — I’d get to work understanding. I wouldn’t just let the moment pass, or nod along to the group opinion. But I know you have to practice responding to that kind of challenge. You have to practice letting yourself be challenged, be discomfited, be changed. Art helps you practice living in that difficult lonely listening receptive space. Something new may happen here. Something you can’t summarize beforehand. You have to be there yourself, figuring it out, not sure what could happen next.

When I imagine an act like O’Connor’s today, I imagine how social media would respond. Social media makes people feel lonely yet not practice being lonely. Quite the opposite. It’s designed to drive us into like or dislike, affiliation or opposition, retweet or quote tweet. Engagement is rarely dialogue. Get on a side and fight. Build a brand, get those likes. This mode discourages the slow work of listening, receiving, interpreting, responding, dreaming, playing, being in conversation and changing together. And so it discourages solidarity, which is a form of love we all need. I tend to think it’s no coincidence that the same media beloved of anti-worker anti-democratic billionaire oligarchs — their racism and sexism so often extremely public — is designed to discourage the slow attentive practices of dialogue, imagination, compassion, and arduous organizing that are the bases of everyday people’s power. How convenient for them if we just perform and divide and brand ourselves endlessly online.

I want to learn to be lonely together, lonely for one another. This is what I hear in the word solidarity, which in English paradoxically reminds us of solitary — as if the first step toward community is to accept the fear of being alone. What if no one claps? The loneliness of O’Connor’s protest was on behalf of others (“because nobody ever gave a shit about the children of Ireland,” she’d later write). In the interview the next day, she says she wanted to “create an opportunity for people, including myself, to say how they feel.… I couldn’t find any way of saying it anywhere, and there didn’t seem to be any way for anyone else to say it, and so I thought, well, fuck it.” How do you learn something you don’t yet know how to know? How do you say something there’s no way to say? If we’re lucky, we live in a time when people are able to boldly work on questions like these, in public, on our behalf, and survive. But that’s where our own work, the work of listening to and for one another, must always begin.