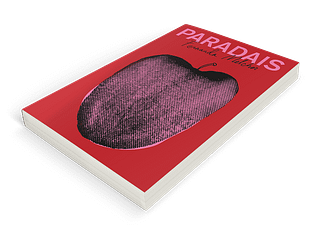

Getting Lost

Annie Ernaux

Translated by Alison L. Strayer

Seven Stories Press, pp. 240

You can’t deny that the pleasures of reading an acclaimed author’s diary — bound and copyedited and available for purchase to anyone with $18.95 — are closely analogous to the pleasures of snooping. This is doubly true when the events of the diary have already been transformed into fiction. Annie Ernaux’s latest book to be translated into English, Getting Lost, is an apparently faithful reproduction of the diary she kept during the affair that inspired her 1992 autobiographical novel, Simple Passion. The novel is an act of artistry. The diary is a scabbed-over wound. Its beauty and meaning — which are considerable — come from the tension between the diary’s immediacy, candor, and occasional luridness, against its intellectual heft as an artifact documenting Ernaux’s artistic process. Getting Lost marries the high with the low, the petty with the sacred, the cerebral with the profane, in an exhilarating descent into abject desire. In the foreword, Ernaux addresses why she chose to publish the source material, when the novel it inspired is freely available: not only was writing the diary “a way to save life, save from nothingness the thing that most resembles it,” it stands on its own as a piece of art. There is a feverish clarity to Getting Lost, a sense of writing through rather than about. “I perceived there was a ‘truth’ in those pages that differed from the one to be found in Simple Passion — something raw and dark, without salvation, a kind of oblation. I thought that this, too, should be brought to light,” Ernaux writes.

Running from September 1988 through April 1990, the diary documents Ernaux’s affair with a married Russian diplomat, S, thirteen years her junior. Ernaux is in her late forties, divorced with two grown children, living alone outside of Paris. The affair becomes the narrative thread of her life, superseding all else. She writes of suffering in love, keenly aware that she is more attached to him than he is to her, but is matter-of-fact about her need for it anyway: “But what do you do without a man, without a life?” Reading Getting Lost, I was reminded of a line from Carole Angier’s biography of Jean Rhys: “[her] life really did seem to be the same few scenes re-enacted over and over.” Entry after entry describes Ernaux waiting for S to call. Entry after entry recounts her fear that the affair will end. In entry after entry, she frets that he does not love her. The same images, themes, and fixations recur: her sense of herself as both a mother and a whore to S, her search for perfection in both love and writing, her conflation of love with death. The repetition is relentless and hypnotic, sometimes verging on dull, but her awareness of it never falters. She at times reduces her themes to shorthand, perhaps as bored as a reader might be, tersely recording “Love/death, but oh so intense.” The shortcuts only draw the reader in deeper, allowing Ernaux’s voice and fixations to echo in one’s head.

From the repetition and occasional artlessness emerge surprises. I don’t think it’s crass to acknowledge the thrill of reading Ernaux’s frank accounts of sex, which range from sensual to amusing: “I realized that I’d lost a contact lens. I found it on his penis.” There’s both eroticism and a kind of dry humor in the way she documents the sex. Ernaux luxuriates in its physical intensity — “My mouth, face, and sex are ravaged,” she writes in a happy post-coital reverie — and documents her exasperation with her lover’s cheap Russian-made underwear and refusal to remove his socks. There’s no performance to the sex scenes in Getting Lost, as the diarist has nothing to prove and no one to entertain. Nothing about them feels fake, and therefore nothing about them feels embarrassing.

But while the book might be erotic, it’s never anything so dull as romantic. This is a real-time account of an abject, obsessive love affair that is consistently clear-eyed and even objective in the author’s understanding of her lover’s flaws and the limits of her own feeling. She coolly notes S’s traits that are repulsive to her — misogyny, antisemitism, a belief in the death penalty, acquisitiveness, status-obsession, an affection for The Price is Right — without excusing or apologizing for them, occasionally reveling in them, occasionally condemning them, and always aware of what her reactions indicate about her own failures. She openly wonders if — and by the end, acknowledges that — her fixation on him is merely a transference of her exotified interest in the Soviet Union. The nakedness of that doubt, and of the ready admission that the love is neither intellectual nor spiritual but entirely carnal or, at best, geopolitical, is acute. She loves him because of two extremes of scale: he knows how to fuck, and he represents a country. The man is almost absent, subsumed by the animal and the national.

These revelations are possible because the genre of the diary is entirely lacking in modesty. Ernaux has not concealed or polished her petty feelings, her summation of S’s wife as “dumpy,” her annoyance with her children (a good, if perhaps unintentional, running joke is how often her sons appear as unwitting obstacles to the affair). But it’s Ernaux’s reflections on her writing that emerge as the most potent thrill. “I want perfection in love, as I believe I attained a kind of perfection in writing with A Woman’s Story,” she writes. Elsewhere, on rereading an earlier book of hers, she sniffs, “This book, written in a very conversational style, is much more profound (with regard to words and the real) than the critics said.” The unselfconsciousness of ego, the transparency, the casual claim of perfection — where does anyone get to write like this except in their diary? Especially, let’s be frank, a woman? This is perhaps the true exhilaration of Getting Lost, moreso than its wit or sordidness. It’s an unmediated glimpse into how the author relates to her literary output, pride and disappointment dispatched matter-of-factly, nothing hidden or demurred or merely implied. No false modesty. No modesty at all. Here is what she thinks of herself.

The focus on the personal, though, can result in a kind of airlessness. In all these thoughts, desires, memories, and dreams (which are recounted frequently, both more interesting than they ought to be and less compelling than they need to be), where are the rooms? The expressions? The hand gestures, the city streets, the half-drunk coffees in chipped cups? Are we to be trapped for 240 pages in a psychic spiral of repeated abstractions? Ernaux is aware of this lack of anchoring physical detail, and at one point mourns it: “I would have liked to write down the details of each meeting — imagined, planned in advance: 1) the dress I wore, 2) the things I made to eat, 3) where I was when he arrived (also planned). Mise-en-scènes that add so much beauty, raising life to the level of a literary novel. But you have to be able to afford this luxury.” The diary’s failures as a narrative are inevitable — at one point Ernaux dryly reflects, having finished entering twenty-six years of her journal onto a computer, that “it’s not much of a story, just a layer of egocentric suffering.” Characteristically, though, the humor of the diagnostic quip almost makes up for the stretches that drag. Ernaux is incapable of writing a bad sentence, even if the book’s language trends toward the quotidian. She remains lucid and witty even in the most dashed-off entries.

Still, when beauty occurs, it feels like a miracle. In one rare descriptive passage, Ernaux returns to London after a long time without visiting and finds a place that was once meaningful to her irrevocably changed: “No more movie theater, no tobacconist’s (it was called ‘Rabbit’), no little café where the youth of 1960 gathered round the jukebox and that bespectacled woman washed cups amid the noise and exclamations. She lives only in my book of ’62–’63, which is unpublished… ” True to the form, most descriptive beauty is rooted either in memory or in imagination. Some of the best writing in the book comes during her projections of life after the end of the affair: “In my mind, I see the summer palace of the Tsar, near Leningrad, where there are buried water jets that soak you if you happen to walk over them. I’ve never given them a thought since the last time I was there. One day, I’ll return to Leningrad, as I’ve returned to Venice so many times, but by then I’ll be an old woman, and I don’t know how to say tempo fa in Russian.” And some of it is not beautiful at all, but rather an uncategorizable mix of poignant and disgusting that differentiates Getting Lost from overly stylized treatments of similar subject matter: “The emptiness of it lands on me all at once, the dream of days gone by. I’ll probably never see him again, although he only leaves on the fifteenth. But I cling to this tiny hope. The day when I consign to the dirty laundry the two pairs of my sperm-soaked underwear from this evening, I will probably be cured.” One isn’t sure whether to weep, wretch, or chuckle.

By the end of the diary, Ernaux is already contemplating the novel she might write about her experience: “A book that could start with ‘From such-and-such a date to such-and-such a date, my life was given over to a passionate affair,’ etc.” This is remarkably close to the actual opening line of the first full chapter of Simple Passion: “From September last year, I did nothing else but wait for a man: for him to call me and come round to my place.” But note the transformation: the shift from the passive voice (“my life was given over”) to the active (“I did nothing else but wait”). The latter version has greater weight and irony, conveyed by the contrast between the sharpness of the “I” and the inherent passiveness, the negation, of its action. There’s also the gap between “a passionate affair” and simply “a man,” one arguing for its importance and emotional intensity, the other arguing nothing, synecdoche and understatement, the man standing in for passion itself.

Perhaps this is the true joy of Getting Lost: the fictionalized version of the affair might be tighter and more polished — more tempered — but it cannot produce the same sense of active, immediate, unmitigated creation. “Truth can only rule in writing, not in life,” Ernaux reflects. A diary is unique in being both.