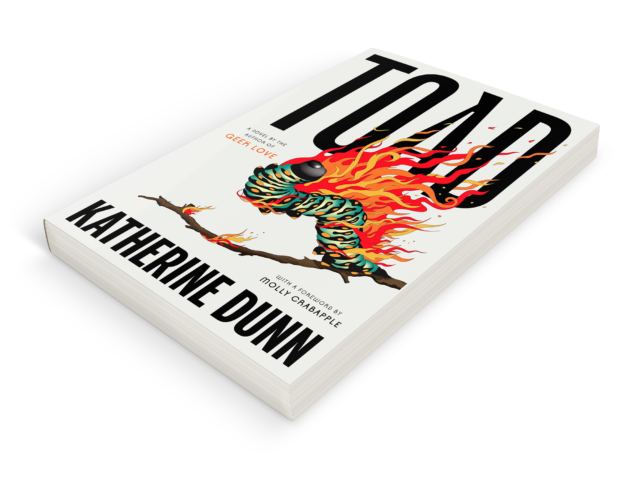

Toad

Katherine Dunn

MCD, 352 pp.

In a cabin, somewhere outside Portland, a newlywed couple prepare to deliver their child. Both of them — Sam more than Carlotta — are gangly and vaguely unclean in an affected way (barefoot, too groovy for soap). They’ve planned for a home birth because “doctors are horseshit, Indian women didn’t pay attention until they knew it was time and then they just went off by themselves and had their baby”; also, because they think it will distance them from their middle-class upbringings in the suburbs of New York and Palo Alto. Sam says that childbirth “is the kind of event that puts you so close in touch with the nature of things that you could never quite be the same after… So I decided I could deliver the baby myself.” For an afternoon he professes his desire to move to India to study midwifery, but this idea is soon discarded for the next in a long line of slipshod life plans: starting a communal farm, an herb-gathering business, escaping Walden-like into the wilderness to practice Zen Buddhism while Carlotta darns his socks. For some reason this “blathering mysticism” is perceived by his peers not as dilettantism or a rather insidious appetite for cultural appropriation, but as a form of ingenuity, of intellectual ambition. Of course, when the baby finally arrives, Sam flees the cabin, unable to handle the material turn of his theorizing: “as long as he’s warm and gets love and enough to eat, isn’t that what babies need?” Several months later, Sam and Carlotta’s pioneering experiment in rural Montana meets an abrupt end when the baby freezes to death.

Toad, Katherine Dunn’s third novel, written in the seventies but unpublished until now, comes closest to lucidity in moments like these: when the dry humor for which Dunn is known edges into something resembling a serious engagement with the racial and domestic politics of the liberation movement. Sam “talks about the ice in the bucket,” Carlotta says, “but he doesn’t mention how the bucket got up the hill.” In the novel, statements of this nature feel sparse, appearing too sporadically to consolidate into a cohesive critical statement — perhaps less because of a lack of conviction on Dunn’s part than because of the book’s unwieldy structure.

The novel is divided into three storylines, each concerning a different period in the life of the narrator, Sally Gunnar, an elderly woman who had been a college friend of Sam and Carlotta’s. The inciting incident of Toad is a meeting between Sally and a former acquaintance of hers, whose impending arrival prompts Sally to reflect on her youth in the sixties and its aftermath. From here the novel spins back and out, shuffling between Sally’s memories and her observations of the present. The present-day Sally has grown comfortably (if somewhat sourly) into hermetism. Afforded a “small but sufficient” monthly disability stipend, she shies away from company almost entirely — except for her goldfish and a garden toad — preferring instead to “sit at a heavy desk before the fire and brood over petty annoyances, manufacture antique responsibilities.” The collegiate Sally exists mostly as a vessel through which Dunn delivers Sam and Carlotta’s narrative. There are also occasional passages dedicated to an in-between Sally, sixteen years post-college, now “gray, dull and bereft of will.” She falls in and out of relationships with uncaring men, slices the finger off her manager at the donut shop, and attempts suicide.

The Sam-and-Carlotta portions of Toad are perhaps also the more successful of the bunch because they hew closely to the scenes of Dunn’s own years at Reed College, where she was a student in the sixties. The images and characters that populate those sequences are cohesive in a way that is never achieved in the jumble of passages concerning middle-aged Sally. It is the presence of this third timeline that causes the most trouble for the book. What before might have operated as a simple, successful frame narrative — the regular interruption of the elder Sally’s voice adding context and consequence to a tale of misspent youth — is turned into a puzzle of times, places, and persons by the introduction of another, less integral timeline. When successful, the use of a convoluted framing structure has its advantages, especially in the context of a complex personal history. That was Faulkner’s approach in Absalom, Absalom, where multiple narrators take stabs at compiling memories into a nonchronological history of the Sutpen family. The difference here (putting aside the obvious discrepancy in the novels’ ambitions) is that Absalom deploys its chaotic narrative deliberately, in service of a larger refrain about memory and retelling, while Toad seems blissfully unaware of the chaos it has created. Storylines jostle against one another not only for primacy of importance, but for rights to the narrative space required to become coherent.

Among all this, there are sequences of remarkable clarity. Dunn has a carnal eye for detail — the “liver softening in a bag” on the floor of the Rambler, the friend always picking his leather pants out of his crotch — these moments of intensity spring forth when she allows herself to luxuriate in a single scene or image. In one memorable section the elder Sally spends nearly five pages dissecting the act of eating a Volcano chocolate bar — “the first touch of the very tip of the tongue to this pale miracle induces a moment of surprise, a reorienting of the senses after the roughness of the surrounding case. The texture of the white center is silky, not as resilient as young flesh.” There is hardly a moment to breathe, though, before the chapter jumps into yet another memory of one of in-between Sally’s failed relationships, which is neither necessary nor particularly interesting. It’s trickier to remember to care about how Sam and Carlotta might, to quote Stuart Hall, “represent the return of an otherwise affluent, middle class, and potentially ‘arrived’ group to the disguise of poverty,” when any appearance they make is squashed up between elder Sally’s gardening sessions and middle-aged Sally pissing on the roof of a car.

Questions that beg answering when recovering an author’s unpublished work are, of course, why should we revive this novel, and why now? Recent trends in both publishing and academic research tend toward what the scholar Nonia Williams has called “a purely celebratory recuperative mode” that remains bound up in the fact of a certain novel or author’s former neglect. Quite often these are entirely worthwhile efforts that confer much-deserved attention on works of great value but little esteem (Persephone Books and NYRB Classics have been especially successful with this formula), but this is not always the case. In the instance of Toad, “why now?” is mostly straightforward: Dunn’s son, Eli, discovered the manuscript among her things after her passing in 2016. “Why?” is more elusive. One answer is that Dunn remains one of our most curious and beloved authors, and the publication of Toad sheds some light on her earliest ventures in writing.

Born in Kansas in 1945, Dunn spent her childhood traveling with her family between seasonal tenant-farming gigs, before finally settling outside Portland at the age of twelve. Parental abuse drove her to leave home at seventeen and join a group of itinerant magazine salespeople; that job would last her until she got to Missouri, where a bad check landed her in Jackson County Jail. Her brief incarceration there served as the material for her first novel, Attic, published a decade later in 1970. After jail, Dunn returned to Portland and began attending Reed College on scholarship in 1965. She met Dante Dapolonia, a key figure in her life to follow, during a winter break in San Francisco. She moved countries with him several times, fell pregnant, and gave birth in Dublin, later returning to Portland and leaving Dante when their son was seven. As a single mother, she made a living waiting tables in diners, tending bar, and working odd jobs — the period during which she wrote Toad. Along with Toad and Attic, Dunn used her life as fodder for one other novel: Truck, a tale of hitchhiking, published in 1971. The three form an obvious triptych, with common elements including wayward adolescents, prurience, and a fondness for filth and excrement. Stylistically, they’re all recognizable as a young writer’s imitation of Kerouac. Truck and Attic soon fell out of print and memory; even now they often fail to consistently rate a mention in write-ups of Dunn’s work.

Today, of course, Katherine Dunn enjoys a reputation as a cultish writer of the assiduously perverse, chiefly due to her iconic 1989 novel Geek Love, which garnered a nomination for the National Book Award. The novel is the story of a family of mutant carny children who are born out of both the love and the radioactive experiments of their parents. There are several pickled fetuses, a circus cult of voluntary dismemberment. A brother who engineers the rape of his conjoined twin sisters by a circus giant (“spurting like a cockroach oozing eggs as it dies”) only to lobotomize one sister during the pregnancy that follows. These are the sorts of images that populate Geek Love, and — perhaps unsurprisingly given their graphic nature — the sorts of images with which Dunn is most associated. This novel seems to inspire a unique kind of fervor: from the way fans talk about Geek Love, an unfamiliar audience would be forgiven for believing it causes readers to become physically ill in response, or that there are gaggles of teens tattooing character’s names up their backs in twenty-six-point Lucida Blackletter. The novel owes its cult status not only to its body-horror elements, but to its engagement with more quotidian and familiar themes. That is to say, Geek Love is also a domestic novel about family, nonconformity, and the horrors of capitalism. “What greater gift could you offer your children,” suggests the matriarch of the family, “than an inherent ability to earn a living just by being themselves?”

Any characteristic nastiness of Geek Love has been displaced, in Toad, onto the figure of Sally herself. Odious and cantankerous, she’s always “snuffling” or groaning, imagining her own death and that of her goldfish. While the chapters allotted to collegiate Sally are almost impersonal — less interested in endowing her with subjectivity or developing her interior life than they are in recording the actions of Sam and Carlotta — the elder Sally is intensely solipsistic in her narration of her day-to-day and of her middle age. The novel’s grotesquery here emerges in the violence of Sally’s thoughts about herself: she is “a mooning, gyrating, strenuously passionate mammal,” a heap of “great white mounds of flesh,” a “second rate masturbatory instrument,” “cross-eyed,” “ravenous,” “sagging.” The enormity of her self-loathing is such that it begins to seem incongruous, too vast to be contained believably in one character’s mind. In these moments the guise of the narrator falters, revealing Dunn as author — still in her twenties, trying to figure out how to properly voice her characters. It seems to me only a young person could envision their elderly protagonist saying, “I am an old fruit; my juices have evaporated, and I am tough and flexible.”

The novel in its entirety proves slippery, eluding easy characterizations. While it has political elements, it isn’t a political novel, nor is it a campus novel or a domestic fiction, though it contains both the motifs of a campus novel and the trappings of domesticity. The use of first-person, so firmly in Dunn’s wheelhouse by the time she published Geek Love twenty years later, is lacking here when it comes to the elder Sally’s narration, and Toad at times provides readerly satisfaction only in that it gives scale to Dunn’s evolution as a stylist. It seems possible that the story of Toad is to be found in what is absent from the text: in the silence of the younger Sally, in the ultimate lack of a conclusion to Sam and Carlotta’s story, in Sally’s unwillingness to confront the memory of what befell them. I would like to read generously, to assume as well that there is something to be said for the all-too-conspicuous absence of civil rights or women’s lib from the characters’ experience of the political sixties. It is to Dunn’s benefit that it remains challenging to decipher what is substance and what is coincidence — to discover, in other words, if there might yet be a baby in the bathwater.