Like other children of my time and place, I watched films from Hollywood in the first years after World War II, although I believe I watched fewer than most children. I watched perhaps twenty double-feature programs from 1946 to 1948. The films were mostly cowboy films, in black and white, and I watched them on Saturday afternoons in the Lyric Theatre, Bendigo, of which I remember only that the floor was quite level, so that the screen always seemed high above me and remote.

The films I watched made me discontented. Scene after scene disappeared from the screen before I had properly appreciated it; the characters moved and spoke much too fast. I hardly ever got the hang of a film, as my brother would say afterwards when I asked him to explain what I had missed.

What I looked for in films was what I called pure scenery. I thought of pure scenery as the places safely behind the action: the places where nothing seemed to happen. Occasionally I glimpsed the kind of scenery I wanted. Behind the men on horses or the encampment of wagons was a broad tract of tall grass leading back to a line of hills. When I saw any such banal arrangement of grassy middle distance and hilly background, I tried to do to it something for which the simplest word I could have found was swallow. I wanted to feel that waving grass and that line of hills somewhere inside me. I wanted grass and hills fixed inside the space that began, as I thought, behind my eyes.

I was not so literal-minded that I was troubled by cartoon images of a greedy boy with his cheeks swollen by a segment of landscape-pie. Yet the word swallow was not inapt. Getting the scenery from outside to inside seemed to engage me in some kind of bodily effort. And if I did not actually think of mouth or stomach, I could still see myself crouching over scenery made somehow conveniently tiny; the scenery brought so close to my face that the familiar became blurred, and strange details filled my eyes; some crucial moment arriving for which I had no words; and finally the scenery safely mine, a piece of plain with a rim of hills floating inside my private space, and rather higher than lower, as though my space was a sort of walking Lyric Theatre and the watching part of me was on the level floor far below the screen.

But I was hardly less discontented after I had absorbed a slab of pure scenery than beforehand. Even in my private space, that scenery was still merely visible. Yet I had hoped to experience my scenery more completely. I had hoped to feel, or even to taste, the qualities that had made a plain of grass and a line of hills seem from the distance peculiarly mine. If I had been subtle enough, I might have understood that the watching part of me could do no more than watch. Even if the watching homunculus (or puerculus) had performed a further swallowing ritual, a further watcher would still have been no more than watching.

I had first been attracted to my scenery because nothing seemed to happen there; my grasses and hills were never the site of the frantic action that took place in the foreground of films. But when I was tired of waiting to understand my empty places, I allowed certain things to happen there. My scenery became the setting for most of my imagined adult life.

I spent much of my childhood assembling elaborate daydream worlds that I thought were foreshadowings of my later life. Even at thirteen I was filling an exercise book with the pedigrees to the third generation of an imagined herd of Guernsey cattle that I intended to own one day, and with maps of my dream-farm showing how each paddock was differently stocked in each season of the year. At the same age I built from wet clay a Trappist monastery — half a span high and two metres square — and wrote down the names of all the monks, together with their roster for celebrating mass in the main chapel and the private oratories.

In my pure scenery at Bendigo I was not yet a dairy farmer or a monk. I was not even wholly I. The man of the silvery grasslands and grey-black hills was more American than Australian. His face and body were those of a cartoon-strip hero, Devil Doone. Only his thoughts were mine — or what I imagined at eight or nine would be mine twenty years from then.

That man — dark-haired, broad-chested, and quietly confident — lived in a place named Idaho. As soon as I had learned to read an atlas I had discovered that in America, quite unlike Australia, a man could travel inland without confronting deserts. In a popular song broadcast from 3BO Bendigo, a chorus of sweet female voices sang of the hills of Idaho. The actual Idaho was near enough to Texas and the Santa Fe Trail to have caught the eye sometimes of a filmmaker from Hollywood. And so my pure scenery led always back from the crudely imagined America of films toward the hills of my Idaho.

Far back in the seemingly empty land that was all but overlooked by the makers of American films, the Man of Idaho owned an enormous ranch. Yet the ranch, for all its size, was hardly visible from the few roads in the neighborhood. It lay in a shallow part of the landscape, between two gentle slopes that looked from a distance like the one gradual hill. Any fool, I thought, could have located his ranch in some steep valley behind mountain peaks, like some lost world in a comic-strip adventure. But then the very mountains that were meant to hide the secret place would actually tempt and challenge intruders. The Man of Idaho laid out his ranch, his gardens, his house, and the rooms inside it with cunning and pretense. Everything looked ordinary and uninviting at first glance. Bands of cowboy-actors could perform their absurd routines almost at the edge of my hero’s property but quite unaware of the riches hidden from their view — just as the people around me in Bendigo could not guess what was doubly hidden inside me.

Although he was a considerable landowner, the Man of Idaho was an indoors man. I had not heard that phrase in those days; I first read it years later in an account by Hugh Hefner of his way of life. But the Man of Idaho was an unusual sort of playboy. The only pleasures he indulged in were the pleasures that I had decided were the most lasting and satisfying.

Two events in my childhood impressed me so deeply that I have still not traced the whole pattern of their influence in my thinking and feeling.

I was one of a line of schoolchildren shuffling through the dust under the elms in Rosalind Park and up the hill toward the Capitol Theatre to practice for our end-of-year concert. High on the hill, we climbed a wooden staircase toward the rear door of the theatre. On the last landing of the staircase, and just before I stepped into the dark theatre, I turned and looked back. Half the city of Bendigo lay below me. The shimmering iron roofs and drooping treetops, the glimpses of orange-gold gravel — everything I saw begged me to stare and interpret. I was looking at a map of the richest pleasures I knew. The long summer holidays were only days away. Anything I could fancy myself doing on blazing afternoons or in the long hot evenings — the site of it was hidden in that intricate pattern of roofs and trees.

Inside the theatre, waiting for my eyes to adjust to the dimness, I expected to feel deprived of my sight of the city. Instead, my sense of place was rearranged. I was somehow within the city, equidistant from every point in it, as though each place I had admired or guessed at when I saw it in the sunlight was now pressing against the outer wall of the theatre; or as though the map I had lately thought of as outspread was now shaped like one of the rings of Saturn and encircling me in the darkness. I was in the best possible position for inspecting any point I chose in the city. And for as long as I stayed in the darkness, the city would strain to press even more closely around me.

The Man of Idaho knew what I had learned in the Capitol Theatre. He knew that the way to understand a place was not to go on staring at it but to turn your back on it. The best vantage point for studying a brightly lit landscape was a dark place within the landscape. The Man of Idaho kept to his house. In the twilight behind his drawn blinds, he understood the pure scenery all around him.

Looking at Bendigo from inside out was the first of my two important events. The second was my father’s putting into my hands a copy of the mid-week edition of the Sporting Globe with its page of photographs of the previous Saturday’s races in Melbourne.

A living racehorse stood only a few meters from where I sat looking at the Globe. I had helped my father feed and groom the chestnut gelding that he owned and trained; I had worn in front of a mirror the yellow and purple silk jacket and cap that comprised my father’s colors; I had not yet seen a thoroughbred race run, but I had seen harness races around the showgrounds at the Bendigo Easter Fair and seen black-and-white newsreel film of abridgements of Caulfield and Melbourne cups. Until that day, though, I had not been moved by racing. Studying the pictures in the Globe, noting how certain horses improved their positions from the turn to the winning post while others lost ground, I began to see each race as a complex pattern unfolding. Then I thought of the spectators, each hoping for the pattern to unfold in a certain way. When I stared at a picture of a field at the turn and pretended not to have seen the same field at the finish, I could imagine many possible unfoldings of the pattern. And each race was only an item in a much larger pattern, for each horse had raced in other races in past weeks, and would add more strands to the pattern in weeks to come.

My first sight of those photographs was the beginning of my lifelong obsession with horse racing. But what I did next was not to ask my father to take me to the next Bendigo meeting. I went into the house to devise my own sort of racing.

I began with marbles for horses and a short straight course across the floor of my bedroom to the skirting board on the far side. I steadied the marbles on the linoleum with one hand, then swept them forward with a ruler held in the other hand. The race was never satisfying. It was over too quickly; I had to shuffle across the floor beside the field, trying to observe the changing patterns and then to memorize the finishing order before placegetters and also-rans bounced back from the skirting board and milled around in a throng.

Then, on a momentous afternoon, I marked out an elliptical racecourse by scoring with a pencil the faint nap of the worn rug in the lounge room. I pushed a field of marbles forward by short stages with my eyes averted; I used my index finger to find each marble and then to nudge it forward with its fair share of force. When every marble had been sent a little way forward, I looked again at the rug. I studied the changes that had taken place in the field and wondered about each horse in turn and about the owners and trainers and supporters whose fate was bound up with the changing pattern beneath me.

The Man of Idaho was even more fond of racing than I was. As a boy he too had fingered marbles around a rug. But as a man of independent means he was free to own or train horses or even — if I could have imagined him shorter and lighter — to ride them. Instead, he shut himself away in his spacious house, in the hidden hollow of land in the pure scenery of America, and played racing games for days and weeks on end.

His racecourses were billiard-table smooth and built into the floors of his vast rooms. His horses were battery-powered toys of the quality of Hornby model trains. The jockeys wore actual silks more dainty than dolls’ clothes. The forward motion of the horses during a race was imperceptibly slow, as though the Man of Idaho watched from the top level of an enormous grandstand, or as though he had more than a lifetime to appreciate his world.

In 1960 I thought I was running out of space. I wanted to be someone other than I seemed to be, and I thought I had first to surround myself with new space. Writing this today, I see that what I needed was imagined space and not, as I thought then, actual space.

I used to look at maps of Victoria, trying to find a certain country town. It was to be a town with unusually wide streets, a very large block of land for each house, a deep and shadowy verandah around each house, and behind each front door a wide passage leading back between cavernous rooms. I wanted to live in one of those rooms, with the blinds drawn. I wanted to live as a writer of fiction. My fiction would be about the people of the town, whom I would have observed from a safe distance. My books would be published under a pseudonym so that the people of the spacious town would never know I had observed them.

Sometimes I looked at maps of America, and every week I read Time. I had not forgotten my pure scenery or the Man of Idaho, but there was no room for dream-landscapes in the America I read about. America was for businessmen who wore buttoned-down collars or farmers who wore American Gothic costumes. Even Idaho was only a name on a map showing who was going to vote for John F. Kennedy and who for Richard Nixon.

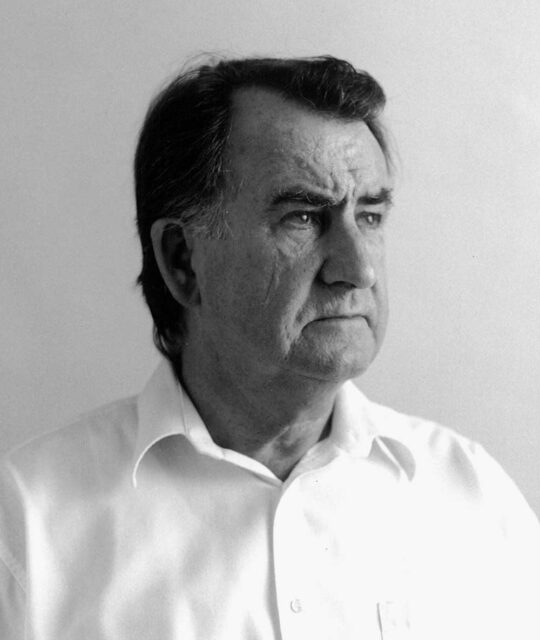

Then I read On the Road. Chris Challis in Quest for Kerouac (1984) writes of all his friends remembering afterwards where they were and what they were doing when they first read the book that changed their lives. I can remember those details for dozens of other books that did little to me, but I have no memory of actually reading On the Road. The book was like a blow to the head that wipes out all memory of the recent past. For six months after I first read it I could hardly remember the person I had been beforehand.

For six months I believed I had all the space I needed. My own personal space, a fit setting for whatever I wanted to do, was all around me wherever I looked. The only catch — by no means an unpleasant catch, I thought at the time — was that other people considered my space theirs too: my space coincided at last with the place that was called the real world. But the world was much wider than most people suspected. I saw this because I saw as the author of On the Road saw. Other people saw the same streets of the same Melbourne that had always surrounded them. I saw the surfaces of those streets cracking open and broad avenues rising to view. Other people saw the same maps of Australia or America. I saw the colored pages swelling like flower buds and new, blank maps unfolding like petals.

I saw all these sights in broad daylight. I pitied the boy who had tried to carry off to his private theatre the silvery backgrounds of films. I moved to the back of my writer’s filing cabinet my folders of plans for imagined racecourses, my color-pencil sketches of racing silks, my furlong-by-furlong charts of dream-races. (This, I thought in 1960, was my craziest project of all. In my sixteenth year I had suddenly gone back to my private racing-world. I needed no marbles or rug — only pen and paper. After weeks of work I had perfected a scheme in which every detail was determined by the occurrence of certain letters of the alphabet in passages of prose on pages opened at random.) Now, all I needed to do as a writer was to set down what was in front of my eyes.

I had found in On the Road only what I needed to find; I had learned about its author only what I needed to learn. I thought of Jack Kerouac as a man not much older than myself, doing in America in 1960 what I was doing — or about to do — in Australia. I placed him not in New York City or San Francisco but somewhere between the Mississippi and the watershed of the Rocky Mountains. I only had to think of him in Nebraska or Iowa for the grass-colored surfaces of those places to burst out of their rectangular borders and to stretch and undulate until they covered over the old, cramped America that had seemed, from the vantage point of my childhood, to lie on the other side of Hollywood.

Six months later, so little had happened in those bloated prairie-landscapes that I had turned my back on them and looked again at what I thought I could be sure of. Later still, I began to write a novel about a city like Bendigo where a boy played with a toy racecourse that turned into the landscape of his childhood, and toy horses that turned into the competing themes of his dreams. (There was much fiction in the book. The champion racehorse was named Tamarisk Row after the trees in the boy’s backyard; my own champion horse had been named Red River.) I noticed further books by Kerouac, but I thought they were all later books: books written after he had come in from the road; accounts of his ditherings in coastal cities that meant nothing to me.

I was finishing the last pages of my novel about Bendigo when I learned that Jack Kerouac had died in Florida in October 1969. I read of his death in Time, which had published so many harsh reviews of his books. Jack had died an alcoholic’s death, and the photograph in Time of a bloated and dejected man seemed only a warning of what happened to those who swallowed alcohol instead of pure scenery.

A few years later the first of the biographies appeared. In 1976 I bought and read Kerouac, by Ann Charters. One of the appendices of this book was a chronology, the first I had seen for Jack Kerouac. Until then, I had preferred to think of Kerouac’s time on the road as linked with my own years of confusion: I saw Jack as wandering vaguely westward in the late 1950s — only a few years before the hippies. (These, in their turn, were already coming in from the road in 1976 when I first read Charters.) In fact, Jack Kerouac’s first trips across America had been made in the 1940s — in the years when I was watching my first American films, looking for the first time toward Idaho, arranging my first dream-racecourses.

But even before I read the chronology, I had learned what mattered much more to me. From the first chapter of Charters’s book I learned that Jack Kerouac, as a boy of twelve, and about ten years before I ran my first race on the loungeroom rug, rolled fields of marble-racehorses across the linoleum of his bedroom in Lowell, Massachusetts. Ann Charters reported few details of the marble racing, but after I had read Dennis McNally’s Desolate Angel (1979) and then Tom Clark’s Jack Kerouac (1984), I understood how Jack’s racing-world had been organized.

In his dream-racing, Jack had achieved much more than I had. But this statement has to be qualified. Jack was twelve years old when he ran his first races, whereas I was only seven. And I was racing marbles without having seen an actual race meeting, whereas Jack went often with his father to meetings in Boston. And the racing-world that I devised on paper at fifteen was much more elaborate than Jack’s operations, although I had used it for only one meeting — recording all the details for a single race could take a whole afternoon or evening.

The chief difference between Jack’s races and mine was that he had always rolled: his races were brief and hectic. Jack’s marbles gathered momentum down a sloping board, then hit the floor and hurtled across the linoleum. Apparently, Jack had never thought of slow-motion races around a rug, of studying the patterns of gradual change, of prolonging his pleasure.

While his races were being run, Kerouac (baptized Jean Louis Kerouac) saw himself as Jack Lewis, owner of the racecourse, chief steward and handicapper, trainer and jockey, and owner of the greatest horse of all time, a big steel ball-bearing named Repulsion. While my marbles were arranged on the rug I was a figure rather in the background. My horse, Red River, was a dull-brown marble that had to be held up against the sunlight for its rich color to be observed. Red River was no champion but his owner, watching the races from some tree-shaded spot at the edge of the crowd, had reason to hope that his day would come. Jack’s races were run on winter afternoons to the sound of music from his wind-up record player. The only sound I heard from my place on the rug was the flapping of blinds drawn against the sun and the hot wind from inland. The racecourse was the center of my dreams, but there were places farther off. At the end of the day, Red River and his owner went home into their pure scenery where nothing more eventful than dreaming took place.

It was nearly ten years after Kerouac’s death before I read Dr Sax. Until I read it, I had thought I had only the biographies to tell me about the racecourse in the upstairs bedroom. Until then, in my view of America, the land was a network of the journeys and stopping places of the man who had locked away his racecourse in a gloomy room, had traveled in the same westward direction that most Americans traveled, and had seen a land like my Idaho on his travels but had passed it by.

Dr Sax was as much a shock to me as On the Road had been. I saw Jack Kerouac climbing up to cramped, wintry New England. I saw him look back once at the sunlit prairie states and then go into the twilight, into the place where he could see from inside out.

Everything I had wanted to know about Jack’s racecourse was there, in Book Two of Dr Sax: detailed form guides, calls of memorable races, the sounds of glass and steel and aluminum, imagined afternoons of bright skies and a fast track, and remembered afternoons at Narragansett or Suffolk Downs among rain-sodden, thrown-away tote tickets. One more vista of America opened out for me. “The Turf was so complicated it went on forever.”

I have mentioned only the outlines of a complicated pattern. I am still reading and re-reading Kerouac’s books, and each new biography; still adding to my view of America. (I have used “America” rather than “USA” in this article because Kerouac was born into a French-speaking family of Canadian immigrants and because he lived for several periods in Mexico, where, in fact, he wrote Dr Sax.)

The latest biography, Memory Babe (1983), by Gerald Nicosia, is the most detailed yet. From Nicosia I learned that the adult Jack had often played a game of imaginary baseball using a pack of cards he had devised himself. He had the cards with him in 1956, during the summer that he spent as a fire-spotter, alone on Desolation Peak in Washington State.

In my own pure scenery, the far line of hills was supposed to be Idaho. But from the vantage point of the Lyric Theatre, Bendigo, Desolation Peak and the Cascades are only a few degrees to the west from Idaho. And if I have lost sight, for the time being, of the Man of Idaho, I can still see Jack Kerouac on Desolation Peak with his baseball cards, playing a game of dreams within dreams.