I didn’t get the joke. At least that’s how I initially thought I was supposed to hear Fiona Apple’s “Hot Knife.” Every fan I knew brushed it off as a cheeky jump-rope rhyme, a charmingly bathetic finale to the waves of emotional intensity that build throughout the previous nine tracks on her 2012 album, The Idler Wheel Is Wiser Than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do. They all would have agreed with Autostraddle writer Rachel Kincaid, who recently placed “Hot Knife” at the very bottom of her list “Every Fiona Apple Song, Ranked by Existential Despair”: “This is Fiona Apple’s version of [Beyoncé’s] ‘Countdown’ and it’s such a delight every time. No existential despair! Just a hot knife.” Why didn’t I share their unequivocal delight? Was I trying too hard to take “Hot Knife” seriously?

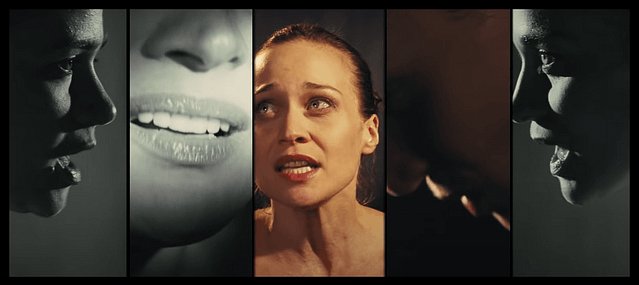

I stopped asking these questions when Apple released the music video a year later. Something pierced me in the sight of Apple striking a kettledrum, gazing heavenward like Renée Jeanne Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc, and flexing every muscle in her body as she whoops and warbles alongside her sister, fellow singer Maude Maggart. I was moved by the intimacy of the video, directed by Apple’s ex-boyfriend Paul Thomas Anderson. His collage of close-ups suits the song’s successive layering of cyclical vocals, accompanied by that lone drum and a bit of piano, and his unpredictable shifts between black-and-white and color reflect the tension and richness of Apple’s composition. I described the video to everyone I knew as a perfect match of sound and vision, and I begged each of them to watch it with me. But I still couldn’t say what exactly “Hot Knife” meant.

That summer, I was twenty-two and vertiginously in love with a man named Ryan. For our first date, he brought a stack of books we could read together, in case I got too shy to make conversation with a stranger; I didn’t, but I appreciated that he’d discerned both my literary tastes and my social anxiety from my OkCupid profile. This was the first of many sweet gestures that won me over, as did Ryan’s playful, charismatic presence: within a week, we declared our love and began discussing the future. He excited me, but sometimes he frightened me. A month or two into this honeymoon, for example, as we reminisced about our upbringings, Ryan blithely recalled the physical force his family often used to communicate anger. He laughed about the times he and his relatives would slap each other or pin someone to the ground, shooting me a grin that said, “Funny, right?” Unnerved, I asked if he would ever use that kind of force with me. He demanded that I apologize and berated me for questioning him. Of course we would never hurt each other; we loved each other. How dare I hurt him by suggesting otherwise? Clearly I hadn’t gotten the joke.

These memories unexpectedly resurfaced when I read Apple’s 2020 New Yorker profile, in which she details her “painful and chaotic” relationship with Anderson, whom she dated circa 1997–2000. He never hit her, Apple said, but he threw furniture, pushed her out of his car and onto the ground, whispered insults in her ear at parties: “he was coldly critical, contemptuous in a way that left her fearful and numb.” When Anderson directed the “Hot Knife” video in 2011, he and Apple had been apart for more than a decade:

By then she felt more able to hold her own — and she said that he might have changed. Yet the relationship had warped her early years, she said, in ways she still reckoned with. She’d never spoken poorly of him, because it didn’t seem “classy”; she wavered on whether to do so now. But she wanted to put an end to many fans’ nostalgia about their time together. “It’s a secret that keeps us connected.”

Am I guilty of that nostalgia? Am I indirectly endorsing Anderson’s cruel treatment of Apple by making substantial contributions to this video’s YouTube view count (2.7 million, as of this writing)? But why did she choose to work with him then? Apple had previously made four videos with Anderson while they were still dating, but at this point she had her pick of illustrious directors, and they could have selected almost any track from The Idler Wheel. Why this joint project, their only post-breakup collaboration so far? That may remain a secret, but even without knowing these two artists’ shared history, you can hear Apple reckoning with both the delight and the despair of such a double-edged relationship in “Hot Knife.”

The song begins with a proposition: “If I’m butter” (antecedent), “then he’s a hot knife” (consequent). Why this conditional phrasing? Throughout The Idler Wheel, Apple tests the logical and ethical limits of analogies like this. In “Werewolf”: “I could liken you to a werewolf, the way you left me for dead, but I admit that I provided a full moon.” Here and in “Hot Knife,” she refuses to shirk accountability behind the smokescreen of figurative language, instead using metaphor and simile to fine-tune her self-examination: I could liken him to a hot knife if I admit that I’m butter — a soft, malleable thing, liable to be sliced and melted. She might be describing the causal sequence of a hypothetical role-play: I’m not butter, but when I act like butter, he becomes a hot knife. Or she could be identifying a particular affect, a vibe: Certain circumstances bring out my butteriness, and these same circumstances bring out his sharpness and heat.

In any case, Apple gives little context for the alchemical reaction between this knife and butter. Is this a pleasurable union or an unsettling violation? Another inscrutable lyric: “He makes my heart a CinemaScope screen showing a dancing bird of paradise.” (A notorious fan of nonhuman mating rituals, Apple came up with this image after watching an episode of Planet Earth.) In this song’s surreal narrative, who is screening this footage, and who is the intended viewer? Does the thought of this man produce involuntary visions of tail-shaking birds in Apple’s heart, or is he deliberately evoking these sensations in her? It’s not clear who has the upper hand in this seduction.

Then comes a twist of the knife as Maggart joins Apple for the backing vocals: “I’m a hot knife; he’s a pat of butter. If I get a chance, I’m gonna show him that he’s never gonna need another.” Has a new character entered the song, or do these two voices share the same perspective? In other words, is the “I” who originally posited that he’s a hot knife if she’s butter the same “I” who now reverses the scenario, with no ifs or thens? Through dizzying melodic and lyrical counterpoint, Apple once again shakes up the balance of power. She’s gonna show him that he’s never gonna need another, but there’s a catch: “if I get a chance.” Is this man so domineering that she can’t get a word in edgewise, or is she the only one stopping herself? Whatever care or aggression she receives from this enigmatic man, neither party holds unilateral power; she can be butter, she can be a hot knife, or she can be both at the same time.

So can I. But not even an artist as influential as Fiona Apple could have taught me that secondhand. Throughout our two and a half turbulent years together, Ryan became increasingly volatile and reckless, and I justified wounding him with my increasingly desperate escape tactics — lying, gradually withdrawing, ultimately abandoning him — as necessary self-defense. I wasn’t wrong to feel unsafe with Ryan, but I know that’s not the whole story. Rehearsing offhand anecdotes about the violence in his family might have been his way of defusing the pain they held, and he probably felt just as scared and vulnerable in our relationship as I did. Maybe he got all along what I get only now: neither of us was the victim or the villain. More often than not, I was both the butter and the hot knife.

I sit up a little straighter whenever I hear Apple abruptly shift to the second person: “You can relax around me.” (Was that Ryan’s intended message when he, smiling coyly, handed me a Kimiko Hahn collection on our first date, as if beckoning a timid dog? Was he also testing whether I would bite?) I can imagine Apple mollifying the man on her mind when he sees the knives come out, perhaps making a truce with someone like Anderson: Don’t worry, I won’t divulge what’s happened between us; our secret’s safe with me. Or she could be breaking the fourth wall, trying to put her audience at ease with this uncharacteristically up-tempo number: You can dance to this one if you want! But if that’s what Apple is doing here, then the ambiguity of her lyrics belies this invitation: if you relax your ears too much, you might miss this deceptively frothy song’s trenchant core.

And then you might miss the fourth and final vocal part, in which Apple’s contralto dips so low that it’s barely audible over that rumbling kettledrum: “Maybe you could teach me something; maybe I could teach you, too.” Part of me hears Apple echoing the disappointment Sheila Heti’s narrator expresses at one point in her novel How Should a Person Be?: “He’s just another man who wants to teach me something.” But Apple isn’t singing about just any man; she clearly sees potential in her seesawing power struggles with this one. You could dismiss this line as a stale remark about learning through suffering, but considering Apple’s numerous songs about running as fast as you can from heartbreak, I hear it as a new resolution to stay with the trouble, not just for her own sake but also for this man’s edification.

What follows may be one lesson they’ve offered each other: “Even just to reach is a triumph.” Whoever this man is, he isn’t close at hand. Perhaps Apple is, as she sings in “Valentine,” “amorous but out of reach,” distantly longing for a new object of affection; perhaps this is a man she left behind long ago. Either way, if you’re the kind of person who wonders, as Apple does, how you can ask anyone to love you when all you do is beg to be left alone, then yes, approaching someone who inflames such fervor is a feat worth celebrating. And in the end, Apple grasps what she’s been reaching for: “Now I really got a hold on you.” This could be just a clever reversal of Smokey Robinson’s “You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me,” but I’m more inclined to hear Apple breaking a curse as she concludes this hypnotic song: Now that I’ve figured out the spell you cast on me, I can meet you again on my own terms.

I think of this closing line whenever I play Apple’s subsequent album, 2020’s Fetch the Bolt Cutters, and remember how long I took to fetch the bolt cutters with Ryan, when I was too worried about protecting myself to own my capacity to hurt someone I love. I had to learn my culpability the hard way by going through a series of other relationship implosions, enacting a version of the repetition compulsion, which Freud defined as the drive to revisit earlier traumas in order to master them, the way a child might turn a distressing memory into a game: “At the outset, he was in a passive situation … but by repeating it, unpleasurable though it was, he took an active part.” As I’ve progressed through this game over the past decade, “Hot Knife” has been my soundtrack, reminding me not to cancel Ryan altogether but to keep reaching back to my memories of him as a way of loosening his grip on me. Ryan and I haven’t spoken in many years, but I still think he could teach me something. Maybe I could teach him, too.

Repetition also charges “Hot Knife” with its incantatory power. As Apple circles around her knife and butter over and over again, inspecting them from every angle, you can hear her teasing out her ambivalence and divining some new wisdom from this situation. I can only speculate on the traumas Apple might be revisiting and working through in this song, but I can see the triumph on her face in the video’s final frame — the face of a woman ready to set herself free.