22 SEP 22

I spent the morning in the air conditioning, trying to focus on booting my comet. Eventually I got to a clean white home screen, which told me it was sunny and 80 degrees in Miami. The Assembly was just getting started. The information we’d been sent promised that you could lift weights that morning at Muscle Beach, and that everything would be free. I put on my yellow sunglasses.

My GPS took me down a boulevard studded with palm trees to Muscle Beach, an outdoor gymnasium with a view of the ocean. There was a woman holding a plank in the air, but she wasn’t my target. Instead I turned my eyes to a group of five guys standing with their hands hanging by their sides. They formed a half-circle with room for me to join it.

Where is everybody?

“I guess everybody got here at ten, bench-pressed for an hour, and then went to get brunch,” regrets a boy in a baseball cap, looking down at his phone and waiting for the Assembly group chat to respond to the message he’s sent from ~bollet-polpub, his planet.

“There was no real meetup,” offers a man in a German accent. “There’s actually a drone flying above us with a camera on it.”

He pauses for a second.

“And the real meetup is watching us from an air-conditioned bar.”

Everyone laughs nervously. I look up, but all I can see are palm trees.

“The gigachads are all gone, I guess you’re stuck with us,” a man says to me, hitting a green Elf bar as we walk away from the water and introducing himself as ~tiller-tolbus.

A muscular programmer leads us to the restaurant where everyone is supposed to be while joining a conference call through his AirPods. As we walk, ~tiller-tolbus and ~bollet-polpub take turns explaining Urbit’s cosmology. On Urbit, there are comets, planets, stars, and galaxies. Each of these “ships” represent various levels of ownership on the digital land that is Urbit. Galaxies can spawn up to 255 stars, stars have ownership of 65,535 planets. When a star is born, ~tiller-tolbus explains, it takes the suffix of the galaxy that produced it. “Is this all making sense?” ~bollet-polbus asks, as we walk past a Victoria’s Secret.

A panelist explains Urbit to me as a “clubhouse where we hide from the AI.” Over the course of the weekend, bit by bit, members of Urbit community describe it as a peer-to-peer networking system that aims to eliminate the need for giant servers, like those used by Twitter or Facebook, companies which present you with advertisements and sell your data in return for free and easy access. Planets, ships and galaxies are cryptographic assets, so, when you get one, you own your own access point into digital communications. Right now, Urbit feels to me like another app, a place where you can join groups and chat, but its long-term ambition is to revolutionize the way we interact online with each other. It was founded by software engineer-turned-political theorist Curtis Yarvin, known as the “father of neoreaction” for his blog posts, which express the view that American democracy is ruled clumsily by “the Cathedral” — a term he uses to refer to the marriage between elite media and academia — and advocate for the institution of a monarchy run like a corporation in its place. Yarvin himself has said that Urbit is written in Martian code; Assembly lore has it that it was delivered to him by aliens while he was on an acid in the Mojave Desert. I think I understand the concept of peer-to-peer networking when a writer, who seems to have learned about Urbit quite recently and become a staunch supporter, tells me that it’s like two people using paper cups connected by string to talk to each other.

We pass by a seven-story parking garage, the venue for tomorrow’s conference. Urbit’s logo is projected on the wall in orange light. We slow down so that ~bollet-polpub can send the group a photo.

~bolpus-polpub sees a man he recognizes seated outside a Cuban restaurant and whispers to me that he is a star-owner named Dashus. ~bolpus-polpub asks him if he was the one referenced in the article, if it’s him who had the elaborate conspiracy theory about Peter Thiel and the book with the LSD in it. Dashus nods slowly. I lean over the chair next to Dashus, sensing that he might be important for my story. Some of the boys go in to eat breakfast, so there’s an indoor group and an outdoor group now. I stay outside. I put on sunscreen, which Dashus doesn’t believe in, and this gets us talking about podcasts.

Dashus maps out connections between some of the panelists speaking this weekend and the shadowy entities they’ve befriended. I pull out my legal pad and try to draw a web. Dashus gives me names that don’t sound like names, but code words made up of five letters. He won’t tell me how the names are spelled if it’s going to be on the record. He asks if I’ve paid attention to who shows up in the backdrop of the Sailor Socialism video. He says if I want to write on this beat, I need to listen to Chapo Trap House’s 623rd episode.

“It’s like jazz,” Dashus says. “It’s the notes they don’t play that you have to listen to.”

~bolpus-polpub reminds us that Beach Registration is happening soon, so we prepare to leave the Cuban restaurant to go meet the rest of the group.

As the bill is getting sorted, Dashus looks me in the eyes and says there is one article about Urbit that has yet to be written. He says he doesn’t think it ever will be written. And, even if it were written, it would be suppressed by the forces at large before it could ever be published. He asks if I know what happened to the last magazine that seriously screwed over Thiel and Yarvin.

“Everyone always talks about Urbit as: this is a grift, or a scam, it’s evil and it’s too complicated, it will never work,” Dashus says. “I’ve never seen an article where someone says: this is a very powerful being created by very dangerous people.” Dashus’ words echo in my mind as we start walking. Dangerous. Powerful.

“The reason the internet is like a dystopian novel is because of the way it’s designed,” ~tiller-tolbus says cheerfully, when I ask him what drew him to Urbit. “That’s why we’re trying to rewrite it.”

We pass some boutiques selling swimsuits.

“I used to use the internet when I was nine years old,” ~tiller-tolbus says. “It wasn’t that amazing back then, but it was way better. It was higher trust, social media wasn’t so combative, if you Googled something there weren’t ten clickbait articles getting in your face.”

He stops to buy a new vape and we wait. At a restaurant across the street, Spandex-clad waitresses roam around holding crates full of nicotine devices. A hostess in a tight green dress tells us it’s happy hour. The afternoon sun gleams down at us.

“It was just a better place, a better community,” ~tiller-tolbus says, recharged. “I think a lot of the things I hate in culture actually come from this fake openness. People think the internet gives them a platform to say anything, but really they’re just giving content to a company that distributes it for them for free.”

We arrive back at the beach where there are around thirty bodies and I meet another girl, ~mallus, by the cooler. While we’re talking about the Urbit group she runs for women and girls, a man in an unbuttoned shirt walks up and steals her sparkling water.

“I’m like, the bad guy,” Pax Dickinson introduces himself to me. “I was the first guy to ever get canceled for tweeting.” He hands his girlfriend back her Spindrift. “I just wanted to see if you’d let me take it.”

Pax warns me that the last time a journalist tried to interview him for a story, she ended up lost at a state park without service. In September 2013, Dickinson was fired from his position as CFO of Business Insider for tweeting the N-word, in a post he said was satirizing Mel Gibson. Curtis Yarvin wrote about Pax’s saga on his blog, and invited him to talk about Urbit, the peer-to-peer networking system he was building out of his home in San Francisco. By the end of that month, Pax was initiated as a galaxy owner. Today galaxies are traded privately with values reaching over one million U.S. dollars.

That night I go to a ceviche restaurant with another writer here on assignment. Just like me, M. is here to get the story, we’re here to solve the mystery. I wait for her and her boyfriend, K., at the wrong Ceviche 105 for a half an hour. I find them at a table with steak and oysters.

K. seems to know everyone here, how remains unclear. I’m told he’s a retired trend forecaster. He can identify all the numbers in the thirty-two-person Urbit group chat, he has the scoop on Remilia’s grooming scandal, he knows where people are getting drunk later, and he has an eye on the other magazines that have sent writers here to get their cut of the action. It feels like we’re in a video game: M. and I are on the opening screen, we’re still picking out what our avatars are going to wear. K. tested the beta, he ran the video game’s subsequent marketing campaign, he vacationed in Monaco with his gains. So, I ask him, what’s the situation here? What’s the deal with Urbit’s apparent deep reach into the mysterious underbelly of New York’s elusive podcast-literary cultural scene? If Curtis Yarvin cut ties with Urbit, why is everyone paranoid about the presence of journalists? I heard there’s a movement downtown to build an alt-right literary scene. Is there truth in this?

“Look, ultimately this is a bunch of nerds,” K. says, leaning in for a second. “And nerds love anywhere there is a story, mythology, lore.”

I ask him why I keep hearing that word, “lore.” I’ve never heard it so many times in one day before.

“Oh, lore is very valuable, more valuable than ever,” K. says, flicking off messages on his cell. “Lore, backstory, depth of information. In the information age, you feel you can either know everything, or you could know everything — you can just look it up. But lore has a mythical dimension. Lore is half what you know, half your imagination. It tells you something may be around the corner.”

M. and I share a cigarette surrounded by the hypnotic chatter of the cicadas, look out at the seven-story parking garage where events start tomorrow and wonder who will write the best Urbit Assembly article.

23 SEP 22

“Wouldn’t it be nice if our services became tools? And if computers became personal again?”, says Josh Lehman, the Executive Director of the Urbit Foundation, opening Friday morning’s Assembly. He is outlining Urbit’s vision to get rid of data-harvesting servers, the internet’s middlemen. He’s on the Galaxy Stage, we’re sitting on green and purple cushions. In front of me there’s a family trying to stop their children from pouncing on the artfully-arranged oranges.

This year’s Assembly, he says, marks Urbit’s transformation from being the product of one company, Tlon, and into a real technology — one that can be used in “strange, chaotic, unpredictable ways” to create “all kinds of beautiful structures.” He presses a button that transforms the screen behind him into a web of the companies, magazines, and DAOs that are now using Urbit. “Congratulations! You all did it.” Everyone cheers.

The easiest way to get on Urbit is to have someone issue you a planet. A star-owner named ~little-fodrex, a bearded man with an NFT-generating chip in his hand, shows me his collection of vanity planets. I choose one that looks like a rabbit. The first invitation fails to send and I’m told I’m getting the classic Urbit experience. I finally get the invite and am about to go home to boot my planet — to use Urbit on your phone, you need to pay for a hosting service— when I hear my name being called. It’s a friend who I met when he was dropping off copies of his new book review in the West Village.

“Ruby here is writing about the event for a reasonably hip New York journal,” Noah Kumin introduces me to a few boys in backpacks, shuffling copies of The Mars Review of Books in his hands — published on 9.25 x 12.5″ paper as well as on Urbit. “If you insult the Chinese every other word, she won’t be able to quote you.”

Noah sees I’m about to leave, so he pulls me aside for a second.

“I know this is new and weird,” he says. I’m nodding.

“And you can write the story, ‘oh, these people are too eccentric’,” he sighs. “But if you look back at history, they said the same thing about railroads, they said the same thing about the computer.”

I ask him what I should do instead, while waiting for the elevator.

Noah takes a theatrical pause, as if he thought about this question in the shower earlier.

“Look, it’s like Chomsky said,” says Noah. “Come at this as if you were an anthropologist from Mars. As if you didn’t know the rules, as if you didn’t know what was expected of you, as if you didn’t know what to think — about Urbit, or Miami, or New York.”

Dashus walks up to the venue as I’m leaving, and I can feel his scowl at my press badge.

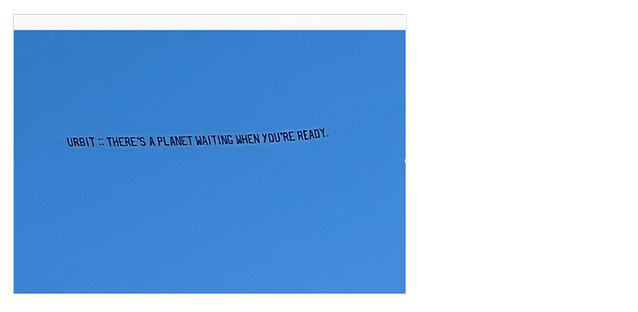

At the cocktail party that night there are miniature tuna tacos floating by. Someone tells me that Anna Khachiyan isn’t coming. She caught a bad vibe. The hurricane. The baby. A Danish girl is talking about the Urbit ad that flew by in the sky earlier. It said, “There’s a planet waiting for you when you’re ready.” She wonders if Urbit is suggesting we leave the Earth behind, its wildfires, its heat waves, the rising sea levels of Miami.

I flutter around the room. Now a fat man from Cleveland is holding two glasses of red wine and following me — he didn’t finish telling me about the star he owns with his father when we were in the elevator. I go to the side of the parking garage to try and hide, where I meet two girls from Minnesota who learned about Urbit on a podcast and wanted to see if they could learn any tricks for building their fashion brand by coming here. A Tlon employee tells me not to be shocked by the problematic things I might hear — he says that hating on journos and saying things you’re not supposed to are just ways people signal they’re on the same team here. He zooms away with a Juul and pack of Marlboro reds and his words hang in the air.

I join K. and M. at a table in the middle of the room. A Substack writer is discussing why ketamine is the perfect drug for our times, and for conferences like this — we’re on a sinking ship and we need an anesthetic. Ketamine takes the edge off social interaction. K. says that a bunch of the Tlon guys are going to see Avatar later.

I talk to Josh Lehman, who was on stage earlier. He’s playing with a pack of cigarettes with the words “Leave the internet behind” on it. I don’t see him smoke a single one; he’s from California. He tells me that, for a long time, the hardest part of his work at Tlon was distancing the project from Curtis Yarvin, who stepped aside so that Urbit would not be constrained by his polarizing reputation. When people offer the critique that Curtis’s viewpoints are baked into Urbit, he says they’re referring to the hierarchy built in to Urbit’s address space, where influence is measured by whether you’re a galaxy, a star, or a planet.

“They look at it and say, that’s not very egalitarian, is it? That’s digital feudalism, isn’t it?” Josh says, refusing the miniature tuna tacos that keep coming toward us and shuffling the Urbit cigarettes. “No. Facebook is digital feudalism. When you don’t have explicit hierarchies, it’s way worse.”

At 11 PM sharp, the lights all go up. Out of the corner of my eye, I see the hand of an anti-porn-crusading Australian inch closer to the thigh of the Minnesotan fashion designer.

“Where do white people go out in Miami?” someone asks as we step in the elevator.

24 SEP 22

Within ten minutes of arrival at the parking garage, in one hand I have a cigarette a Tlon employee rolled for me, in the other a magnesium seltzer. Yesterday, this Tlon employee would not talk to me. Today he’s wearing a press badge ironically, over a shirt that says “I GOT MY THIELBUX REVOKED AT URBIT ASSEMBLY.”

On stage, a man in Versace sunglasses is presenting his plan to free us from the tyranny of the browser. Trent Gilham’s company, Holium, is presenting “Realm,” a feature they are developing on Urbit which will allow users to adjust their screen for different contexts — you could have a realm for your church group, a realm for work, and a realm where you and your friends play poker, he explains to me later. At another panel, a historian-turned-venture-capitalist says, of people living through historical transformations, “You don’t get it at the time. It’s too deep to understand. You see ripples on the water.” Someone thinks they see Bladee in the audience.

Later that day, a group of writers, magazine editors, and filmmakers consider what Urbit could offer the arts. Walter Kirn speaks powerfully about Urbit’s vision to make the internet intimate, describing how writers could use it to communicate with a small, curated audience, rather than “shoot a confetti can at the entire world” and hope their work lands. The panel discusses how Urbit could provide a platform for writers to meet patrons, as opposed to the Substack model, where writers beg for small donations like buskers. The twenty-three-year-old Australian I saw last night uses the question and answer period to outline his plan to get young men to stop watching porn: get everyone off addictive group chat sites, like Discord, and have them onboard Urbit, where they can learn how to grow food and become self-sufficient. “The mind that’s free of addiction can sculpt the world,” he says, when I find him later and become his third Twitter follower.

I meet my friends at the Standard Spa and get ready for the parties that night by putting my head underwater.

That night there’s a mansion party in North Beach and a rave across the Venetian Way in Miami proper: choose your own adventure. My friends and I opt for the party and K. says we’re going to the John Backus’s house. A gated community opens for our Uber and we walk into a house with a white Tesla parked in front of it. In the back of the house there’s an infinity pool. There I make eye contact with a girl in a sea of male programmers. She’s carrying a hologram cutout of a girl with watery eyes. I ask what’s the deal with the hologram character, I keep seeing her. “Milady is all about love,” she explains, holding up the hologram girl. “Beauty, aesthetics, and healthy living.” She pulls me inside to meet some of her friends. “Like, we don’t fuck with seed oils.”

Inside, there’s an anime playing on the flatscreen TV and people playing chess below a six-panel Lichtenstein reproduction. A man is taking a call in the living room armchair. I’m flipping through a copy of Industrial Society and its Future by Ted Kaczynski when I feel a tap on my shoulder.

It’s Dashus. He wants to know how my mission is going — if I’ve figured out anything. About Urbit. Curtis. Thiel. The world.

I think of the anti-porn Australian with three Twitter followers.

“Why did you tell me, on my first day, that Urbit was dangerous?” I ask Dashus.

“How did I know you were going to ask me that?” Dashus says, emphasizing each syllable and chuckling to himself a little. “Urbit’s not dangerous,” he says. “I was just saying that’s a story you could write.” I take a big sip of my Moscow Mule.

“You know, I read that piece you wrote — the one about going to school in California, and reading all those books?” Dashus says a lot of his friends never got to go to college. Firefighting and construction work come up, but I can’t remember exactly what he said, because just as I’m about to run away to the bathroom to write everything down, I’m interrupted by M.

M. says we’re on a new mission. We’re going to weaponize our femininity. We need to find John Backus. She needs a quote for her story from the man whose house this is. K. tells us to look for the tallest man in the room.

We find Backus standing by a large column. He takes us behind an elaborate metal door he needs to duck under, showing us the giant marble bathtub and the collection of Japanese art in his bedroom. So why did you gather us all here tonight? We ask, looking up at him.

“Oh,” he says, rubbing his chin like he never quite thought about it. “I guess I just really like Urbit.”

25 SEP 22

I finally meet one of the legends at Assembly, one of seven boys in their late twenties who have just injected themselves with an experimental gene therapy on a charter city off the coast of Honduras, for life extension purposes. He says he’s getting used to five hours of sleep a night, while hitting a vape, and says he’s never felt better.

“I like this bro science thing,” Pax Dickinson says of the gene therapy boys. “I mean if you look at the history of science, it’s all just guys running experiments on themselves and being like, ‘oh shit, this works.’” Pax’s girlfriend, ~mallus, is sitting with a family from Indiana who tells me they use Urbit to send updates from their farm, like when the ducks lay eggs. LCD Soundsystem is playing. Babies are napping on purple cushions. On the ground there are cigarette butts and orange peels.

On my flight down to Florida, I had wondered if Urbit was an attempt to try and leave the Earth behind, if humans were trying to create increasingly immersive spaces to hang out online until they could get on a space shuttle to another planet. After Assembly, I no longer think Urbit is just a cult for accelerationists, doomsday preppers, and overweight nerds, trying to escape their human form by taking on the names of stars, galaxies, and planets. People kept referencing the idea of going up to an online world that felt more curated and human, so that users could come back to reality with more clarity of mind, more enthusiasm to carry out their projects.

The process of onboarding Urbit is convoluted. Figuring out how to get a planet is not like creating an account on Netflix — it requires looking for information on online forums, a willingness to spend hours completing a task outside of the scope of what’s typically considered pleasurable or productive. Like delving into the lore of a podcast, developing conspiracy theories, or getting into Borges, using Urbit requires a concentrated focus that it is now trendy to call “autistic.” This barrier to entry seems to have shaped the Urbit community into what it was at the moment I encountered it: an ecosystem of people who are skeptical of the codes of comportment on the Earth and the internet, who are drawn to the mythological universe of Urbit because they feel something is false about the way things are playing out on the surface.

I don’t know if Urbit is the next railroad, or the next computer, these are things I grew up with. I’m interested in what Urbit wants to offer writers — a platform that’s more curated, a place of their own to share with a select readership. I’m interested in how the pseudo-anonymity afforded by writing under the name of a planet could encourage writing that’s more schized out and honest.

I go back home. In the room I grew up in, being twelve and feeling somewhat alien, I wrote a quote on the white wall in black crayon: “Here’s to the rebels, the crazy ones, the misfits…”

This article has an accompanying moodboard.