One night in Paris, I saw a ghost. It was nighttime, maybe three in the morning. She stood by the edge of my bed in my studio apartment, an old maid’s room at the top of a building on a crooked street in the Fifth. There was no time to be afraid of her; she appeared and was gone. She never came again.

In her memoir Giving Up the Ghost, Hilary Mantel describes seeing her stepfather’s ghost on the stairway of a cottage that she was about to sell. She considers that the image might be “nothing more” than a prelude to a migraine — for her these warnings often took the form of visions, “floating lacunae in the void, each shaped rather like a doughnut with a dazzle of light where the hole should be” — but she insists on the reality of ghosts all the same.

Sadly I have never had such baroque and outlandish visual warnings that a migraine is about to begin; mine start with a tightening and a throb before they wrench open my skull so I am riddled with knives and retching. I don’t see things that aren’t there; I only feel the pain that most definitely is there, which, as is the way with pain, I alone can perceive, and which, over my life as a migraineur (migraineuse), has often been disbelieved or minimized by others.

Certainly when I saw the ghost I was not about to have a migraine, though I may, I feel I should admit, have been asleep.

I am devastated that Mantel has left us. I love her prodigious works of historical fiction, her arch humor, her way of twisting a sentence beyond what we’d expect of it, her way of confronting the reader with the invisible and chronic pains that are the predicament of the body, her insistence that we take female pain seriously.

But one of the most enduring things I love about Hilary Mantel is that she saw things that weren’t there, that objectively weren’t there, and that she believed whole-heartedly in them. In Giving Up the Ghost she writes about a little girl who died when her nightdress caught on fire, whose picture is kept in a brooch passed down through the family. “It is oval, which is the shape of melancholy, nostalgia, and lost romance.” No it isn’t, not necessarily; an oval is a shape like any other; we merely project meanings onto it. But how breathtaking the way Mantel projects her meanings onto the oval, filling it up with this little dead girl and all the tragedy of her end, as if they had always been there before her birth, just waiting for her, and now they are inexorably there inside every oval.

Rereading Mantel now, I realize: for so long I hesitated, in my writing, to make such declarations. Oval is the shape of melancholy. Even if I’d made this connection myself, I would have hedged in writing it, trying to leave room for the people for whom circles are inevitably sad, or figure eights. Rereading Mantel now, I think: it’s time to make my declarations, stand by my perceptions. If not now, when? Hilary Mantel’s essays remind me of why throughout my life, no matter what has been happening, what joy, what grief, what banality, I have gone to literature, to art: to help me see the things that aren’t there, but also to give me courage to say this is what I saw.

“I am fascinated by evidence of the past pushing through the surface of the present,” she said in a in a BBC documentary about her life and work, Hilary Mantel: Return to Wolf Hall. This is the particular talent of the historical novelist: to see the things that used to be there and aren’t any more. To perceive the traces of the past in the present and to reveal them to other people. She was, in a sense, a psychogeographer, attuned to the psyche of place, and the way that layers of history jostle with each other all at once.

She was very good at evoking what people want and need from places, without, perhaps, even being aware of it. Arriving in the village of Reepham in Norfolk she recalls the town’s process of gentrification, growing to include

a post office, two butchers, a pharmacy, as well as a telephone kiosk: a hairdresser, one or two discreet antique dealers, a busy baker’s shop which sold vitamins and farm eggs and organic chocolate, and a greengrocer-florist called Meloncaulie Rose. A well-arranged town square was surrounded by calm, wide-windowed houses, and a jumble of cottages tumbling down Station Road.

Mention of the station road reminds her of what was once there:

There was no longer a station, though in Victorian times there had been two, and twelve beer-houses, and a cattle market. There had been three churches, but one of them burned down in 1543 and was never rebuilt; the history of the town is of a slow decline into impiety and abstemiousness. On a January day, after I became a resident, a huddled old lady beckoned me from her doorway and looked across the deserted Market Place to the church gates. “What do you make of it?” she said. “More life in the churchyard than in the street today.”

Hilary Mantel was as interested in the life in the churchyard as the life in the street, and she could tease it out like few writers I have encountered. (Even in writing about her work I feel my sentences elongating, can sense that I am rummaging around in my impressions to see what else they contain.)

Of course she was also precise about the historical record. In her short story “A Clean Slate,” about the village of Derwent in Darbyshire where Mantel grew up — a town destroyed to create a reservoir — Mantel’s writer-narrator recalls that when she was a child, “people would tell me AS A FACT that in hot summers, the church spire would rise above the waters, eerie and desolate under the burning sun.” This was not true, she goes on: the church was demolished in 1947. She has a picture of the church in its ruins. But if she were to show this picture to her mother, for instance, who we are meant to infer is one of the people making this claim, “she wouldn’t believe me.… She doesn’t care for evidence. She has her own versions of the past, and her own way of protecting them.” As for the narrator herself, she tells us, “I distrust anecdote. I like to understand history through figures and percentages of these figures, through knowing the price of coal and the price of corn, and the price of a loaf in Paris on the day the Bastille fell. I like to be free, so far as I can, from the tyranny of interpretation.”

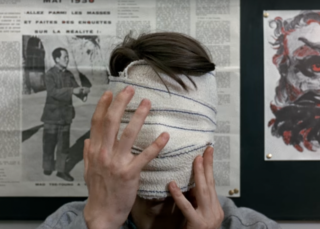

In this story, and in interviews, Mantel spoke of the importance of skepticism toward the kinds of things we find ourselves wanting to believe. This can be as innocent a matter as liking the idea of the drowned spire, but other insidious “certainties” can lead to fanaticism, fake news, and fascism. At the time of her death, Mantel and her husband were planning to leave Brexit Britain, a land where people believe the falsehoods they are peddled because it suits them to do so, and to live out their lives in Ireland, in order to “be part of the big story” of the European Union again. They had already bought a house, which she will now never inhabit, only, perhaps, haunt.

So here we are with Mantel, poised between the irrational and the factual, between a ghost and a dream. “A ghost to me is unexplored possibility,” she says in Return to Wolf Hall. But so is a sentence. So is a new home, an old town, a beloved author. “I learned not to talk to the ghosts,” she goes on, “but to listen.”

I never met her, but hoped, one day, that I would, when I had written something worthy of bringing me into her presence. I feel personally bereft that I never will now, that she has joined the ranks of the ghosts, to whom we can no longer speak, only listen. I have a feeling she will appear to me for as long as I’ve got — I hope she does.