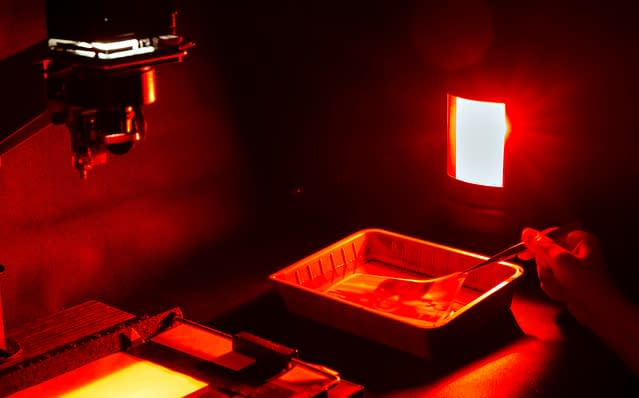

One day, during my second year at university, an email came through on the weekly round-up. We were told that a retired Fellow had donated a monthly sum to restart the college’s Photography Society, and he was looking for someone willing to take charge of the reboot. I agreed to handle it. Mostly, it involved keeping the darkroom stocked, and throwing out expired supplies. Still, I had almost no idea what I was doing.

I ordered the chemicals over the phone from Jessops and picked up the white, sloshing Ilford canisters in the shop in town, then cycled them back up to college in my basket. Often, they went out of date before they were used; but I loved to go down into that basement darkroom under Commons, where there were no windows, just a rusty iron door that led back up to the courtyard. The only thing down there, except for the exposing trays and the enlarger, was an old Casio radio and cassette player, and the only cassette was a late-eighties Philips recording of Holst’s Planet Suite. There was something so camply dramatic about the opening military bars of “Mars, The Bringer of War” filling the small, brick-walled room as I set to work.

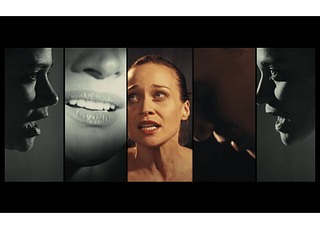

I remember thinking, the first time I saw the photo of Jack taking shape in the developing solution, that it was like uncovering an artifact: taking the plastic tray in both hands and gently rocking the solution over the floating paper, until it sank and was covered, and eventually the more exposed outlines of the image began to appear, emerging out of nowhere. First, the darker background on the white sheet, the far places of the quad where the flash of the camera didn’t strike anything. Then, the image of Jack’s suit, the shape of his body, the dark of his hair and his eyebrows; the hundred little lightbulbs on the tower of the helter-skelter; a food stall; a waiter serving drinks; blurred figures caught smashing their dodgem cars into each other, the electricity sparking on the gauze roof. And then there he was, like a ghost, smiling at me from under the clear solution.

So, although I hadn’t spoken to him for a year or more, and had few physical things to remember him by, I still heard his voice when I saw the bobbing white flowers of the cherry trees in the park that Easter. I sat down, casually, while I was alone in the apartment, and typed Jack’s name into the search engine, expecting the usual list of misdirections and red herrings, but this time the first result was a funeral notice, his name, his town, sadly missed, his sorrowful parents and sisters, and I just stared in disbelief, checking it, reading it over and over to find some mistake, some sign that this wasn’t my Jack, but someone else’s. And then, right there, his photograph, his broad smile beaming out against some alpine background, the hyphen from his year of birth completed, closed off.

And because I couldn’t find anything more of him online, I pulled out the drawer under my bed and searched and searched through all the old albums until I found his photograph. He had come to the Spring Ball alone, and, looking back, that would mean it was a few months after the first time we’d met. I was wandering, drunk, looking for the friends I’d lost, when I saw him standing by himself in the main quad. He had his back to me, but when he turned around I caught his eye and he smiled and I walked over to him, looking down at the floor, scared to hold his gaze. I could hardly bear to leave him alone, even for a minute, was drawn to him with an eagerness that was a sort of disbelief. He was so handsome.

In the October of my second Michaelmas term as an undergraduate, six months or so before I had taken that photograph of Jack at the ball, I unlocked my bike from the sheds at the end of the college drive and cycled into the lowering dusk, down Castle Hill and into the center of Cambridge. My basket juddered along the cobblestones as I went past the colleges of St John’s and Trinity.

I rattled my blue bike along the alley, lifting off and standing up on one pedal, like a postman, until I pulled to a stop by the church, where I ignored the penalty notice and locked my bike to the railings. I’d already had a few glasses of wine back in my college room, hoping to dull my anxiety, and when I walked along the passage to the pub, I could see all the windows already fogged up and hot with condensation, a warm glow of light inside. There were muffled noises, beats, and shadows moving about. It was still nothing like the cheap, rowdy bars I was used to in my northern home town, but it was something, and I was glad to have it.

That was the night I met Hasan, who led me to Jack. The hot downstairs room of the pub was small and filled with young people trying out their make-up and the outfits they wouldn’t get away with in the normal Cambridge bars. I stood by the wall, warm pint in hand, and I wanted to join them – I have always wanted to join them – in dressing up. Skirts and glitter and sequins and harnesses, but then, as now, something held me back. As a minor concession, I used to wear a golden cross earring on my left ear. It hung from the bottom of a gold hoop, which I’d had since I was sixteen, when I had snuck out into town with a friend into the upstairs room of a shop that sold cannabis paraphernalia and poppers and healing crystals. I remember being embarrassed when a boy at school pointed at it, laughing, saying I had got “the gay ear” (my left one) pierced, but there was a glow of pride under the shame I felt, a pride that I had been brave enough to mark myself out. Still, I always felt myself to be looking in on an ideal queerness.

I didn’t want to look as though I was at the pub alone. Every so often, I would walk around as if I was searching for a friend. But, after a half hour or so, the dance floor filled up and I felt less conspicuous. I eased my way into the crowd. Before long I was dancing, or swaying, up by the DJ booth, facing the decks and turning around occasionally to see who was there, hoping to spot a familiar face; and then there he was, Hasan, right beside me. He was much shorter than I was. I hardly noticed him at first, but when I looked down I saw his bright face, his strong jaw, and deep-set brown eyes that kept on catching mine, then looking away, as if it were all an accident. He was French, a gymnast, it turned out, though he’d come to Cambridge to study History of Art, the sort of subject I hadn’t known existed until I got here.

Out of the blue, but casually enough, he told me I should come home with him to meet his boyfriend. His name was Jack and he was “up working late”. Hasan offered the words with a sort of innocence, a secret code for what he actually meant. I was drunk enough by this point that I said “OK,” but I said the word as if I were only agreeing to what was made explicit, and was unaware of the thrill of fear and excitement implied by the subtext.

As we passed along the wall of Caius, I suddenly felt out of my depth.

“Actually, sorry, I think …”

He just smiled at me, and carried on talking.

“Come on,” he said. “It’s freezing out here.”

I was wondering if I was ready to go with him, whether I was ready to take that one step further into the new life I was discovering away from home. Here, I was an adult, all the world of good and bad choices open before me. I looked over to him and assented, not with any gesture, but by turning towards him and following as he walked up to the arched wooden door and opened it, the sliver of yellow light expanding behind him.

Upstairs, the door to Jack’s room was unlocked, so we walked right in. Jack, it turned out, was asleep in the bed — fully clothed, with just a rough-looking blanket curled around his leg, his hand tucked under the pillow beneath his head.

“I’ve brought someone to meet you,” Hasan whispered, though quite loudly, and he said my full name, as though I’d been expected, as though Jack would know who I was, though we’d never met.

Hasan didn’t wait for Jack to wake up, and instead walked over to the small alcove on the far side of the room, where there were piles of books – editions of Attic drama, a bright red hardback of Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things, a few worn-out grammars. They almost looked like they’d been placed there as a prop to signal a studiousness at odds with the rest of the room. Under the bookshelves was a small white fridge, which Hasan opened with a clunk. I looked up, embarrassed at my own curiosity. Hasan took out some beers with screw tops, handed one to me, and then walked back over to Jack, leaning close to him this time, shaking him gently awake and whispering something to him.

Jack turned over and looked across the room, saw me and smiled, saying a sleepy “Hello” as he slowly pulled himself up, so that he was sitting over the edge of the bed, rubbing his eyes, his hair ruffled.

I said, “Hey,” followed immediately by “Sorry.” I didn’t know what I was apologizing for.

There was a two-seater sofa by a small fireplace, in which a few pinecones were propped up on top of each other, and I sat down on it and took a sip of my beer. Jack got up off the bed and came to sit next to me.

“I’ve been waiting for you, you know.”

I didn’t know what he meant. I couldn’t tell if he meant tonight, or if he meant he’d been waiting for me for a long time. I didn’t know whether he meant he’d been waiting for me personally, or if he meant he’d been waiting for someone like me. All I knew, in that moment, was that I was happy to be waited for. For the first time I felt what it was like to be on the receiving end of reciprocated desire. Still, this wasn’t without a sense of discomfort. To know that I had been expected, especially when for me this was all so unexpected, so impromptu, put me on edge. I had the uneasy sense, then, of my own passivity, my own susceptibility to coercion, and felt childish and out-of-depth.

Nevertheless, when he put his hand around the back of my head and brought me slowly towards him, I leant in and kissed him, closing my eyes before our lips touched. We had hardly said anything, but it didn’t matter. I was feeling braver now. I put my beer down and reached my hand across on to his thigh, and after a few seconds he leant back and pulled off his T-shirt, lifting his arms up over his head, so the collar ruffled his hair upwards and he came out of it slightly flustered. I brushed his hair back and kissed him again, deeper this time, loosening into him. Buoyed by a sense of my own reflection in his gaze, I seemed to inhabit myself differently, and I took off my own shirt, too. At this point I remembered Hasan. It was strange to have forgotten him, but I had, and I pulled back from Jack to look around the room, to check if Hasan was OK, to check if all of this was OK, but I saw that he was just sitting on the bed, drinking his beer, watching us, but also looking out of the window occasionally, as though we were perhaps interesting, but nothing outside the realm of the ordinary.

As I was lying there on the sofa, with my head in Jack’s lap, he held the end of a half-smoked cigarette to my lips and I dragged it, coughing slightly. I blew the smoke up into the air away from his face. I could feel the hardness of him pressing gently into the base of my neck, and I looked up at him, altered by the strange angle, and he looked down at me and smiled slightly and took the cigarette in between his fingers and smoked it again, then tapped it against a glass ashtray on the bookcase. Every so often I felt the shape of his erection lift under my neck, then sink again, involuntarily, the blood moving through it. Jack carried on smoking and nodding his head rhythmically, and then slowly swaying it to the music, his legs spread open and me just looking up at him and at the ceiling, then taking another drag of his cigarette as he lowered the end of it towards my mouth and held it to my lips while I breathed it in.

As the beats of the music quickened, catching up with my pulse, he took another drag, and put the cigarette into the little groove of the ashtray. He took my head in his hands and leant forward over me and brought his lips to mine. Slowly, he opened his mouth so that the wreathes and tendrils of blue smoke bloomed out of him and over me, and he kissed me through them, keeping his lips apart so that the smoke passed into my mouth and back into his, warm and visible. Kissing Jack, I was aware of a constant, suspended pleasure – the touch of his lips on mine, the occasional soft bite of my lip, his tongue. It was his way of keeping desire, of holding it at a pitch, in abeyance, without ever satisfying it. The smoke was like pleasure — something we could taste and feel the heat of, but never quite touch.

When I opened my eyes again, Hasan was standing over me, too, and he put his hand in mine, pushing each of his fingers between my own. I lifted myself up, and when he took off his shirt I saw the long muscles of his back and followed them down to the blue horizontal of his underwear. He took my head towards him and tilted it to one side, gently scratching my neck with his stubble, kissing it, and then journeying upwards, where he took my earlobe in his mouth and played with the gold cross earring, tugging it softly with his teeth, taking it just to the edge of pain before letting it go. For hours, then, the three of us moved together, interlocking, a sort of trinity, loosening and tightening, as though between us we might dissolve the boundaries of the self.

On the day I found out that Jack had died, it seemed as though a part of my life, a part that had been suspended in my subconscious, suddenly locked into place. For me, his death began to seem part of a lineage: all these men I knew and walked beside, collapsing under the pressured atmosphere of the world. And I looked to myself and began to see my life differently, as though all the things I had thought or done as I grew up took a new perspective and crystallized. That day, I felt as if we were all walking headlong into some winnowing fire, and the further we walked, the less of ourselves we seemed able to carry with us.

All that afternoon I sat in my room and thought of Jack. I looked for any physical traces I might still have of him, but found only that one photograph. After too long spent staring into the unfocused space between my bookshelf and the far wall of my bedroom, I had lost the sound of his singing. But then, new words seemed to surface and I saw Jack again, walking ahead of me. It was a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins that I had in my mind, but I could remember only the first line: “Sometimes a lantern moves along the night.” Perhaps there was an answer in it, some clue, some remnant of Jack that my subconscious was pushing forward. I went to the bookshelf and took down my old, worn copy of the poems.

Hopkins was a Jesuit priest, a Victorian, and for years I’d read his poems and his diaries and heard him speaking to me. I felt a kinship and an understanding with him. In my mind I had made him into a sort of guardian. He loved other men, too, but could never say it, though his poems are full of their bodies, their beauty. Nature, for him, was the presence of God incarnating through the world.

I found the poem, “The Lantern out of Doors”, and read it, wondering what it was I remembered, what Hopkins was trying to tell me. “Men go by me,” he wrote,

whom either beauty bright

In mold or mind or what not else makes rare:

They rain against our much-thick and marsh air

Rich beams, till death or distance buys them quite.

I saw Jack and the others walking away from me, all those rich beams thrown through the air, and one by one they were going out. I read it again. There was so much I couldn’t know from the poem. I didn’t know how to make sense of it, all this loss, this brokenness. In Hopkins’s poem there is a disembodied light, though we imagine someone to be carrying it. I thought of it again, and of going after that light. “Sometimes,” Hopkins wrote, “a lantern moves along the night. / That interests our eyes. And who goes there?” Where are they coming from and where are they going? “Where from and bound, I wonder, where, / With, all down darkness wide, his wading light?” That disembodied figure, moving through the night, holding up the yellow-angled beams of a lantern. I decided to follow that ghost, back through my own life, through the lives I had known and lost, through the lives I had not known, but wished to know; to skirt the darkness, to walk behind the swinging light, to get to the heart of where it was taking me, which is where, after all, I had come from.