Fiction The Ecstasy issue

In Paris, My Asian Body

By Lin Yu-Hsuan

Translated from the CHINESE by CHLOE GARCIA ROBERTS

My body was was resplendent on the bed from every angle, touched all over by the thousand needles of his delight. At the peak of my climax, I burst into an Oriental rainbow. The Moroccan man may have been watching us. The curtains absorbed the force of his stare, but passion seeped through them like water.

In the early morning I wondered, What does my Asian body mean in Paris?

My classmate Pierre is a beautiful man. To say he is a beautiful man is the fruit of Asian eyes contemplating a European body. His tawny lion’s mane of curls, chest hair prickling out over his collar, eyes the color of an empty sky, over six feet tall—he is the model of stereotypical perfection, as if cast from a mold. The cauldron that made him opened like a clamshell and he rose from out of its depths.

My classmate Shahin is a beautiful man. To say he is a beautiful man is the fruit of Asian eyes contemplating an African body. He has hair like steel wire, radiant black skin, severe features, and meticulously groomed facial hair. He crosses the school library’s glass suspension bridge, and everything around him falls away, leaving behind only the lustrous pearls of his eyes.

Pierre loves to say, Je suis désargenté—my silver leaf has come off. The way his whole person gleamed, it seemed like this could have been true. After making further progress in French, though, I learned that Pierre was actually saying, My pockets are so empty.

Pierre’s pockets are so empty. Pierre likes to bite his fingernails. Pierre speaks carefully and quietly. Pierre is a shop assistant at a bookstore. There, the physical capital of Pierre’s ancestors clashes wordlessly with the economic capital of wealthy Asian tourists. The books are in conversation; the people are in conflict.

Shahin is a Sudanese refugee, his Facebook profile picture is a photo of Frantz Fanon. His timeline is full of poems he wrote in Arabic. I press the translate button to read them and it gives me back unintelligible text:

The inferiority complex of a chemical compound

We do nothing, we just rebel against our own image

#… #… #… #…

The roses must be given to the children in the camp

While he was doing drugs, the darling baby returned

Early breakfast, going to the Sorbonne in Paris to look for his

brother Africa

Dance has already become cartridge lead

The future became their black intelligence

Lacking impartiality in the numbers of black lions

War in the black belt

#!. #!. #!. #!. #!. #!. #!. #!. #!.

Language like a spear launched from the body of the world pierces the

wound of the sky

He had already turned and taken one dose of race

We became Black, it is dynamic, we turn toward blackness, it holds more

value than whiteness

#… #… #… #… #… #… #…

Because demons are not Black

The whole class of eighteen people collaborates on a short film. In the film we recite our own poems. When we reach my part of the film, you can clearly see that my facial features seem to collapse into flatness. No mountains or valleys or wild dense dark forests, I am all alluvial deltas and tiny rice paddies. Low self-esteem has nowhere to hide when the global resolution is so high. Asia’s great twenty-first-century vindication, which began with economics then spread to politics and to the military, has failed to reach the body. Asia has been well-off for over a century, and yet we still see European beauty as beauty. Aesthetics still drags behind politics, the military, economics. Maybe after two hundred years we will finally catch up. After two hundred years, we’ll all be dead. And Pierre and his girlfriend will have their stereotypical names carved on their tomb: PIERRE AND MARIE. She’s Dutch and as tall as he is.

In the short film, Pierre bites his nails.

Shahin does not recite his own poetry.

Shahin recites Valéry.

My poem is beautiful.

In a moment of joy, I throw off my shirt and open the curtains. The Moroccan man stands at the window across the way, just as he has before. The sun is positioned such that when he faces me, he is light and I am shadow, he is shadow and I am light. He’s smoking, his chest is bared, and he’s looking straight at me. His beard is stitched with sunlight, the lines of it as sharp as a ceramic knife. He steps out of an Islamic miniature to gaze at my Asian body, and I pierce the glassy air to gaze at his North African body. Under my window is a blossoming cherry tree. Under his window is a palm tree. Across the courtyard garden, our bodies mirror each other.

A map of the world lightly floats down over our neighborhood, aligning with the complex in which we live. On this map, the flower garden between us is our Europe.

A while ago I read, on a French internet forum, an Asian user’s pleas for advice. He said he was only two inches long and didn’t dare to even hold a woman’s hand, for fear those slender white hands would start exploring and his secret would be broken, the meaning of his life smashed like an egg.

His comments were met with a chorus of concern. Very few people laughed at him, the clamor was largely made up of courteous inquiries. A North African user wrote back and said he himself was nearly eight inches, which had already caused some awkwardness, though two inches was particularly small. He knew of some corrective surgeries that might help. There was another North African woman user who advocated vehemently for love. She insisted that love could cure all ills and was the medicine for everything. It was all so warm and convivial. What a great multiracial nation.

The man taps his cigarette ash, and then returns to a meditative stillness. The capillaries on my arm are as legible as scripture. When he gazes at my Asian body, what is he thinking?

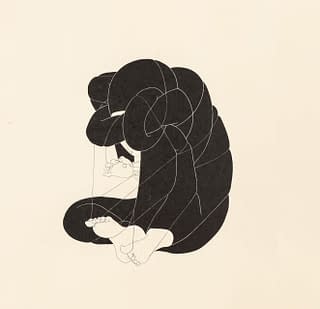

But what is an Asian body exactly? The world’s focus on the European body is already excessive, the grace bestowed on it so great, that an Asian body is drawn to its own extinction.

An Asian body faces the mirror, the mirror’s surface scorches and burns, and there is no one in the mirror. Like a heavenly fire, the great colonization consumed the beauty of millions. Out of the ashes, a sinister and foreign spirit of beauty was resurrected. The Buddha and the demon and the mandala returned to us from the West, and from then on Asian people saw only their own transfigurations in the mirror, they no longer saw themselves.

The Asian body and Asia itself are both blurred. Asia is a product of Europe, Europe whose absolute blue borders were painted by Christianity. Asia was named by Europe: in Greek, Asia in Latin. Asia is defined by Europe: sharing a continental plate, it is anywhere Europe is not. Formerly, Asian people did not know they lived in Asia. Asian people said they lived in: the Nine Provinces of Yu Gong, the land of the rising sun, the eight wildernesses, the six boundaries, the three thousand worlds unbounded. Asian people said they were: people.

When Europe arrived, their gods framed the universe, their people framed Asia. Asia is everything that Europe is not. Asia is Europe’s perfect inverse. Europe is homogeneous, Asia is heterogeneous. Asia holds every type and color of person—red, yellow, white, black, and the green of youth—as well as the five major religions of Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam. Its kaleidoscopic aesthetics, later completely destroyed, flowed from the Caucasus Mountains all the way to the Japanese archipelago. And then the people of Asia were no longer people, they became an entity called Asians, a kind of humanoid the deep-eyed, peak-nosed ethnic group of the ancient northwest treated as a curiosity.

If you’ve never gone to Paris, you don’t know that the best-selling item in the Carrefour stores is a factory-produced Buddha head, neatly cut off at the neck, made to be placed against window curtains or next to wineglasses. The Buddha is also an Asian person.

The Eastern body became a battlefield, magnetized toward the West. Impelled by aesthetics, each Asian body is forced to rise, to spin around, to regard itself, to distort itself, to falsify itself, and then to slouch toward the perfection of the West—that world of eternal bliss.

The celebrated cosmetic surgery in East Asia looks toward the West, instead of being guided by its own millennia of beauty. And so the people of the East have gradually come to resemble the people of the West, the aesthetics of the Eurasian continent stretching out in a ten-thousand-mile-long Möbius strip, and the distant foreign world becomes a distorted reflection of the homeland.

In Asia, I was not in the least aware of my body. Only after arriving in Europe did I discover that my body carried Asia within it. In Taiwan, a body might be seen as old, young, tall, short, fat, or thin; a body is not understood in terms of its geographical origin. In Paris, when I travel by subway, I am weighed down by other people’s curiosity. It rides the shifting expressions in their eyes like currents, offers itself to me shyly, like a present. And it’s as if, when they see me, I were the most beautiful bloom in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. I became self-conscious, I saw the watermark on my own body: my dark black pupils, my straight hair. I fell prey to the gazes of strangers that routed me out just as their forebears had hunted and killed forest tribes to collect their skulls. On the Paris Métro, I define for 2.2 million pairs of European eyes the lands and people that their ancestors once claimed.

I thank them. I thank you. The Asian eye covets the European body, the European eye covets the Asian body. And in between these interweaving arrows, my self-awareness painfully yet joyfully carves itself into being.

I am here in this place, but my Asian body is absent. European people who stroll through museums catch sight of their own bodies, omnipresent and omnipotent, in mythic ascension, in golden robes and emperor crowns, in the habits of religious martyrs. One moment they may be an excavated Greek statue lifted from out of the ocean, the next they might become a member of the Protestant gentry in the Dutch Golden Age, necks encircled in stiff lace, and then, for a time, they might be a brutalist self-portrait composed of thick distinct brushstrokes. The European face in history changes and then changes again. The European body is represented and re-created in a thousand brilliant ways: realistic, abstract, in a crowd, as a portrait. After the great colonization, European art subsumed global art. White people saw themselves reenacted, celebrated in song, performed and interpreted on a global scale. The whole of art history is white people drawing their own history. They walk into a museum and walk into an imaginary reality, like a fantasy game. An Italian tough takes a selfie with a bronze sculpture of a Roman emperor. In front of the statue of David, the person helping me take a picture so resembles David he could be a replica. It’s as if David’s spirit were helping me take a picture with David’s corporeal body. In front of me, behind me, all around me: it’s all Davids. Viewing such an exhibition feeds their ego: I may be an ordinary person, but I merit the artistic commemoration of two millennia.

As for Black, sublime, glorious, and profound Black: it is a descent, a retreat, a background, it is a point of contrast, an underlying meaning. If an African body comes to the museum, he catches sight of his representation as Satan, as a savage, as half beast tamed by a white Jesus, as cargo, as enchanter, as a shadow, as a slave girl holding fresh flowers. The museum besieges the African body.

As for the Asian body, it is a zero, it is an absence, it has not existed since heaven and earth began. I steer my Asian body through the exhibition space the way a wheelchair-bound person trespasses into a lavish room with no accessibility—but in my case, even the wheelchair is empty. It seems as if I’ve arrived only to fill an empty space. No one asks me to leave, no one speaks to me. I am silent, I am transparent, their eyes cut right through me, they instead perceive a cocktail of everything Eastern. I feel a loss so vast it has lasted for a thousand years.

I finish reading my poem. But there is only silence, and the blankness of an empty sky that fills the small room of this theater on the outskirts of Paris. Seventeen people with seventeen different expressions in their eyes.

Inside this theater classroom, under the high-hanging costumes of past generations of Europeans, our several-month-long writing workshop draws to an end with my outburst.

Afterward, Pierre disagrees with me. He says, “It’s not that complicated.”

Shahin disagrees with me. He says, “It’s not that simple.”

I say, “Pierre, you know you hold an advantage, even though you choose not to acknowledge it. Or if you acknowledge it, you don’t talk about the bitterness that comes with the sweetness.”

I say, “Shahin, it’s not difficult. I’ve noticed your beauty. Your Black beauty and your Sundanese-ness that outshine the white lens.”

Shahin says, “You use European eyes to look at me. You’re not praising my beauty. You’re praising the fact that I happen to have an African body that aligns with European beauty standards. Do you know what the standards of African beauty are? Because by those standards, I am not beautiful at all.

Did you know that using European beauty standards to judge African bodies has resulted in great suffering? On your Asian body is a pair of European eyes. You see me deformed and yourself distorted. The African body is fighting to pick off all these European eyes. As for the Asian body, when will

it have Asian eyes?”

I steer my Asian body away from Pierre and Shahin.

In the gathering dusk, on Line 13 of the Métro, I am inlaid in the crowd, like a wisp of golden clay, like kintsugi.

Shahin publishes a new poem.

I press the translate button, but it won’t translate, all I can understand is that the subject of the poem is the body.

The Arabic alphabet is strikingly beautiful in its blackness, the translate button flashes bright like my white eyes.

After I exploded into an Oriental rainbow, my lover and I began to date. This man was the only person whose ethnicity I could not clearly identify. But he was not blurry. He was as brilliant and relentless as a blade, not stopping until a bit of blood was drawn.

To reconstruct myself through my encounters with other bodies was like making a coin rubbing; by saying what I was not, I arrived at a definition of what I am. Unexpectedly, I found my Asian body celebrated along the way, its path strewn with lanterns, and banners, and songs. The beauty I had assumed I did not possess was brought to the surface.

The last time I orgasmed, I forgot to shut the curtains. The two of us melted into the futon, while, across the way, the Moroccan man rested against his window, like a mirror image, smoking a cigarette.

The following day was Paris Pride. The sunlight was like a knife. I hurriedly threw on some clothes and rushed outside. On the tree-lined boulevard, someone obstructed my path. It was the Moroccan man, my beloved mirror image, his beard as impenetrable as a thicket, on his cheek a tiny rainbow flag.

His body, like his country, was its borders and everything it contained. To his north, Pierre. To his south, Shahin. All that he possessed, I lacked, all that I possessed, he lacked. He told me, “You’re beautiful.” I didn’t know whether he was speaking of me at that moment, or of the moment when I was completely spent in climax. I laughed loudly and said, “You’re beautiful, too.” I lightly kissed the Moroccan man. I cannot say I had no regrets.

In the turbulence of the throng, I caught sight of the man with the undefined ethnicity, the man whom my love defined. He smiled quietly and watched me in awe. He didn’t see Paris, didn’t see Asia, didn’t see a body, he saw only me.