Essay Online

I Wish I Could Stop Thinking About “Mr. Brightside”

What if the 2003 hit song is sad and gay?

By James Frankie Thomas

Imagine two boys kissing: stubble scraping, tentative tonguing, hands wandering. Imagine that they’re best friends, roommates, and totally straight (or so they both believe); they’re kissing as a joke, or an experiment. Can you see this in your mind, cargo shorts and all? Afterward, one boy (the more sensitive of the two, obviously) can’t get the other out of his head. Imagine that boy listening through the wall, anguished and turned on as his friend hooks up with a girl. The boy wonders when he became so obsessed, so abject, so…gay. It started out with a kiss, he thinks. How did it end up like this?

The first few dozen times I heard “Mr. Brightside,” the 2003 alt-rock hit by The Killers, this was the narrative that played out in my head. I don’t think I believed that the lyrics were explicitly telling this story. I never paid close attention to the words. But the song is one of those things you can know, or sort of know, even when you think you’re ignoring it. I admit that at any given moment I was usually thinking about men kissing each other—this is still true—so my initial homoerotic interpretation may say more about me than the song. But regardless of the merits of my case, I was convinced “Mr. Brightside” was sad and gay. It’s amazing how many things are sort-of-knowable in this way, and amazing how long you can coast like that. It wasn’t until the fall of 2017, when I moved to Iowa City for grad school, that I began to wonder what “Mr. Brightside” was actually about.

“Mr. Brightside” was enormously popular with my Iowa classmates, many of whom were too young to remember its original release. They selected it on every jukebox, blasted it at every dance party. The opening guitar riff elicited cheering. I was afraid to ask why, lest I find myself on the outside of some widely shared inside joke. That was how I already felt most of the time, in general, but especially in Iowa, where I could no longer escape the knowledge that I confused others as much as I confused myself. People were constantly asking for my pronouns—they didn’t ask everybody, but they always asked me—and the mere question threw me into stammering incoherence. Whenever I mentioned my husband, whom I missed terribly while we were long distance, I saw the bafflement on people’s faces as they struggled to reconcile my marriage with their impression of me—that I was a lesbian, or barely out of high school, or both, or something else. I felt bad for being so illegible. The least I could do was pretend to be in on the joke of “Mr. Brightside.”

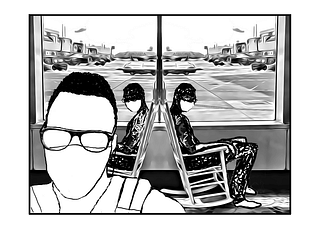

One night I attended a party, cheered along when “Mr. Brightside” came on, awkwardly danced to it, left the party, and began to cry. As I walked home, I tried to call my husband. I wanted to tell him what I was feeling: that I existed less than other people, that at age thirty I had missed the window to become a person, that I wasn’t entirely real. I wanted to hear his voice and know that I was real to him. But I couldn’t reach him, and I didn’t really expect to. I knew he was spending the night with R., one of my best friends from high school, with whom he had grown close since I moved to Iowa. He and she had weekly sleepovers, took vacations together, slept in the same hotel bed to save money. They were open about this with me, which was how I knew they had nothing to hide. They had repeatedly asked me for permission to hook up, permission I felt guilty for denying, but after the fourth or fifth denial they’d finally stopped asking. I still felt uneasy when I thought about it, but I tried not to think about it. Instead, I thought about “Mr. Brightside.”

You’d think there wouldn’t be much left to consider. Few songs have received as much airtime as “Mr. Brightside.” It gets played at weddings, college parties, karaoke nights, football games, and supermarkets. It’s beloved by jocks and frat boys and straight people. It’s one of the most downloaded songs since the invention of downloading. In the UK, it’s the longest-charting single of all time—it’s still charting there, in fact. By most metrics, it’s overplayed, but somehow its popularity has only increased over time. In late 2016 “Mr. Brightside” began to spawn internet memes, so it was at the height of the song’s half-ironic renaissance that I came to Iowa and heard it so frequently I couldn’t get it out of my head. If you’ve read this far, it’s probably stuck in your head now, too.

But have you ever really thought about it?

The peculiar thing about “Mr. Brightside,” compositionally speaking, is that most of it is sung on just one note. That note is D-flat, which is also the song’s key throughout. The singer, Brandon Flowers, begins the song on D-flat and hits it over and over and over, by my count, ninety-six times in a row. While this is monotonous in a literal sense, the effect is not tedious but propulsive, almost autoerotic. The more he repeats the D-flat, the more hotly you anticipate the climactic moment when he finally breaks away from it. This anticipation also serves to distract you from the words, which are Gertrude Steinian gibberish:

Coming out of my cage

And I’ve been doing just fine

Gotta, gotta be down

Because I want it all

It started out with a kiss

How did it end up like this?

It was only a kiss

It was only a kiss

Now I’m falling asleep

And she’s calling a cab

While he’s having a smoke

And she’s taking a drag

Now they’re going to bed

And my stomach is sick

And it’s all in my head

But she’s touching his—

Here, on his, Flowers switches notes for the first time, going down a half-step to C to shift into the pre-chorus and draw the listener’s attention to a naughty little fake-out non-rhyme. Get your mind out of the gutter! She’s touching his

—chest now

He takes off her dress now

Let me go

I just can’t look

It’s killing me

They’re taking control

What is knowable here? That there are three characters in the song: “I,” “she,” and “he.” That “I” is tormented because “she” and “he” are hooking up—or are they? Is it a dream (Now I’m falling asleep)? Or a paranoid fantasy (And it’s all in my head)? How do we square the speaker’s torment with the opening lines, which read like the opening lines of a completely different and unrelated song? Every time I listen to “Mr. Brightside,” some part of me holds out hope that the fast-paced drum track and insistent D-flats will propel me to understanding in the chorus:

Jealousy

Turning saints into the sea

Swimming through sick lullabies

Choking on your alibis

But it’s just the price I pay

Destiny is calling me

Open up my eager eyes

’Cause I’m Mr. Brightside

Here the speaker switches to direct address, deriding your excuses and imploring you to open up his eager eyes. Who are you? You are “she,” presumably, but (as I kept thinking in Iowa) you could just as easily be “he.” Pronoun ambiguity aside, the chorus is word salad. Turning saints into the sea? Lullabies? Destiny? For that matter, ’Cause I’m Mr. Brightside? Why? In what sense is the tormented speaker looking on the bright side?

I’m always doing this, though. I fixate on individual trees, analyzing them down to each twig, in search of an understanding that would come so much easier if I stepped back for a wider view. “Mr. Brightside” is impressionistic, a gestalt, a vibe. Its lyrics were written to be half-heard, not close-read; its music was composed to be felt, not counted note by note on my fingers. Other people have no difficulty recognizing “Mr. Brightside” as a song about a guy whose partner is cheating on him.

This is, in fact, public knowledge. In 2009, Brandon Flowers told the British music magazine Q that he wrote the lyrics to “Mr. Brightside” after catching his girlfriend cheating. “I was asleep and I knew something was wrong,” he said. “I have these instincts.” He got up and went to his local bar, “and my girlfriend was there with another guy.” He ended the story there, leaving me wondering, in Iowa, how he knew for sure. Just being at a bar together was no proof of anything. My husband and my friend R. went to bars together every weekend. They wore couple costumes to parties. They went out to dinner on Valentine’s Day. But they weren’t cheating. I knew this because I asked him, over and over, and every time he reassured me that he would never do that to me. They were just friends. I was jealous and insecure. Yes, I certainly was.

There’s another peculiar thing about “Mr. Brightside.” After the chorus, Flowers sings the second verse—except there is no second verse. It’s just the first verse again, repeated verbatim. This is such an unusual songwriting move that when you Google “songs that repeat the first verse,” all the relevant Reddit results mention “Mr. Brightside.” (None of them mention “I Could Have Danced All Night” from My Fair Lady, but that’s my favorite other example.) In theory it’s lazy and unimaginative, which is why most self-respecting lyricists wouldn’t be caught dead doing it, but like the decision to sing the same note ninety-six times in a row, it’s oddly effective here. At first it comes as a relief—a second chance at understanding! Having just been bewildered by the chorus, I listen with renewed attention, hoping that this time the words will cohere into something I can comprehend. But “I’m coming out of my cage” etc. doesn’t make any more sense the second time, either. Of course, it doesn’t. Simply repeating a nonsensical statement won’t make it make sense. What’s maddening about “Mr. Brightside,” though, is that it almost makes sense. It almost tells a story. It tells this almost-story over and over, hitting the same note again and again, plangent and urgent and relentless.

Ever since the fall of 2020, I’ve been telling the same story over and over: My husband had an affair with my friend. She was one of my best friends from high school. They were hooking up the whole two years I was in Iowa, and they continued even after I came back. He confessed in August of 2020. I left my marriage, and then I transitioned. Sometimes I feel like I’ve told this story so many times that the words have lost all meaning, but I suppose I’ll keep telling it for the rest of my life. One day, I hope, I’ll be able to tell it without my voice going monotonous. Maybe I’ll even tell it in a way that makes sense. Or maybe it’s never going to make sense.

I wish this essay were about a different song, one that hasn’t been played to death. I wish I could decouple the story of my transition from the tawdry heterosexual soap opera of my husband’s affair with my friend. I wish my life were entirely devoid of cliché. But no one is immune to cliché: it comes for you regardless of how smart you think you are. Sometimes the best you can do is trade in one cliché for another. At such times, it can even come as a comfort that so many other people know the same words.

There’s a surprising coda in the final few seconds of “Mr. Brightside.” After running through the verse and chorus a second time, the speaker stops repeating himself and sings a new lyric: I never. He holds that third note (D-flat, of course) longer than he’s held any note in the song thus far. It’s as if a new thought has just occurred to him. But rather than continue this thought, he goes back to repeating himself.

I never

I never

I never

I never

The song ends like that, the thought unfinished. I never what? I have no idea what the rest of that sentence is supposed to be. I think about it all the time. I keep imagining that if I can only fill in the blank on that last line, I will finally understand “Mr. Brightside.” I play and replay the song, trying to figure it out. Even as I write this, “Mr. Brightside” is playing on repeat on my computer, dragging me back to a crowded dance floor in Iowa City. I’m moving in place. I’m mouthing along to words I sort of know. I’m asleep and I know something is wrong. I’m so, so close to getting it.