The Met Gala’s sin, allegedly, was failing to read the room. While the rich and beautiful were walking this year’s red carpet to nowhere, the theme of which was “gilded glamour, white-tie,” there was a harder kind of news: the Supreme Court’s draft judgement on, or against, abortion rights had been leaked. Anna Wintour and company couldn’t have expected that particular turn of events, but given the political situation — gloss that from any angle you wish — it was no surprise that for onlookers in the digital panopticon, the evening, as Jessica Roy at Elle put it, “went from gilded to Gilead real quick.” Most newspapers ran pieces the next day quoting a number of furious Tweets, which said that the gala’s theme was “too on the nose,” or painted the attendees as Marie Antoinettes: “gilded glamour at a time of war, let them eat cake.” America needed political change, and this party was window dressing at best, reactionary at worst.

But for me, the Met Gala didn’t go far enough. Rooms are not meant to be read, then offered more of the same: that’s an algorithm, not an art. Some people desire to be shocked; others don’t know what they desire. This year’s looks seemed to be caviling before the objections they knew would come: the lowlights included Kate Moss’s eventless tuxedo dress, Kylie Jenner’s flat juxtaposition of wedding dress and baseball cap, and Kim Kardashian’s much-discussed but fundamentally dull turn as Marilyn Monroe. I kept thinking of what was missing, and remembered the bombast of Rihanna’s outfit in 2018, when the theme was “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination”: she wore a silver dress and jeweled papal cloak, complete with soaring miter. Designed by John Galliano, the look was equally daring and smart: it flowed provocatively off her legs, while mimicking, with a straight face, centuries of sartorial pomp. Sex, authority, drama, kitsch — all the faces of the Church at once. But this year’s drama seemed unconvinced by its own right to be on the stage. What was needed, to my mind, was the opposite approach: melodrama, or a spectacle so spectacular that it would have drawn attention to itself, and left the spectators struggling, profitably, to figure out what they thought. And I wasn’t the only one. Afterward, looking up what the buzz had been in advance of the Gala, I noticed a quiet refrain: that “gilded glamour” was crying out for one designer and era — Dior by Galliano. In the event, the latter wasn’t represented this year at all.

Galliano was the enfant terrible who made good on his promise, and more. His designs were about flamboyance and sex, combining a restless imagination with a tailoring skill that produced the boldest cuts. He was pulled from penury in 1995 to lead the House of Givenchy, and then, a year later, promoted to Dior. Back then, Parisian haute couture was holding on to minimalism, worried about American grunge and “casual chic.” But Galliano wouldn’t subtract, and would never dress down, so his work took flight instead. For the next fifteen years, his shows became studies in, and of, extraordinary excess. As Ingrid Sischy once put it, each one had an “implicit story, a beyond-just-spectacle theatricality”; the designer was an obsessive researcher, engrossed in the figures and clothes he made. His comrade-in-arms was Alexander McQueen, like him a graduate of Central St Martin’s (and his replacement at Givenchy). Their antics were scandalous; they weren’t the first to put a Gesamtkunstwerk on the catwalk, but few had made such electric marriages of terror, beauty, and lust. As André Leon Talley said in 2003, “you cannot name many people who have completely changed fashion, and John is one of them.”

For a while now, I’ve been fascinated by a TV interview that Galliano gave several years later, in 2013. The circumstances had changed: this was his first appearance on screen after spending two years in disgrace. Back in December 2010, Dior’s creative director had been at a Parisian bar called La Perle, and (as usual) unspeakably drunk, when he launched into a tirade against two women sitting nearby. What started the argument wasn’t clear, but the footage, preserved on YouTube, begins as one of the women asks: “Are you blond, with blue eyes?” Galliano replies: “No, but I love Hitler, and people like you would be dead today. Your mothers, your forefathers, would all be fucking gassed and fucking dead.” The footage didn’t see the light immediately; it seems to have passed into a few pairs of hands — including some in the media — but it didn’t enter general circulation for months, and might never have appeared, except that Galliano, it transpired, had done this more than once. A second recording surfaced in February 2011. Same bar, same time of night, same anti-Semitic rant. This one spread like fire across the web. On March 1, 2011, Galliano was dismissed by Dior.

Juan Carlos Antonio Galliano-Guillen grew up in south London, working-class and gay. It was said that he’d never shown a hint of bigotry before, that he was easygoing and kind in the atelier, that his alcohol addiction was in obvious need of help. Such objections were always doomed. On those evenings at La Perle, the designer was not only offensive, but showed all the flaws that critics associate with the world of couture: shallowness, venality, cruelty. “You’re so ugly, I can’t bear looking at you. You’re wearing cheap boots, cheap thigh boots. You’ve got no hair, your eyebrows are ugly, you’re ugly, you’re nothing but a whore.” It was melodrama gone terribly wrong: Galliano knew he was acting out, but the act was free of irony, built on appalling premises. And, to cap that February night, when the police turned up, he acted like the bar were a stage. He stood up and struck a flamboyant pose, as he did at the end of his couture shows, and declared: “I am the designer John Galliano!” Thus, as the journalist Nina Mandell put it, “he concluded in the most embarrassing fashion,” and his reign at Dior concluded too.

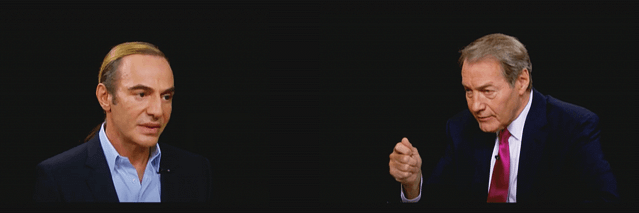

Back to the TV interview: it’s the summer of 2013, and Galliano sits down to be interviewed by Charlie Rose. The host plays the first tape from La Perle by way of beginning his show, and Galliano, who sits opposite and watches it too, looks haunted by what he sees. He’s now sober, wide-eyed, nervous; his face is clean-shaven, and he wears a dark suit with an open-necked shirt, which is worlds from the Dalí moustache and pirate dreadlocks he used to flaunt. At first, Rose is all charm, reminding us how high the designer had risen, how he set up his own label and scaled the heights of Dior, until the words arrive, quite politely: “So, John. How did it all come to this?”

And suddenly, even with two years to prepare for the question, Galliano is lost, exposed. He’s come to live with the humiliation, ossified over years, but now, reliving his initial embarrassment, he doesn’t know what to say. “No one was more shocked than myself, Charlie, I mean I just saw that…footage you showed and it threw me quite.” (Still, he’s more composed than he’d been in 2011, on the day he first became sober and was shown the video by his assistants. “When I saw it,” he told Sischy, “I threw up.”) This interview is a show trial, even if Rose is pretending it isn’t, and Galliano has to speak in his defense, even if he wasn’t asked — even if he doesn’t remember the nights we’re witnessing on camera. So he starts to talk about his drinking, his stress, the drugs, the long nights, tales he patches together, stories of a gay boy at school and a gilded cage at Dior. The interview unfolds, lightly tensed, on the cusp of some obscure upset.

The spectacle of watching Galliano watch himself is, to me, a rare and moving event. It shows us a person being held to account for unforgivable sins, and in doing so, it takes us to the fringe of our social world, where the transgression of taboos forces our reaction to them into view. Galliano’s behavior was always inseparable from his creative approach: his designs were built around characters, historical or imagined, and he saw no need to have restraint. “When I research,” he told Rose, “I really go into it. I need to know everything [about his ideal character]: where she lives, does she read by candlelight or gaslight, the color of her hair dye, the scent on her breath, is it gin, the powder, the make-up… It helps me to create a character. Sometimes taken from paintings — I start by paintings and then I create the character-fiction. So I’m living it, I’m breathing it.”

Galliano’s transgression, then, was partly born of treating the world as a dramatic stage. In a society that doesn’t equate living people and fictional characters, and that abhors anti-Semitism, he plainly deserved his punishment; he lost his job, and the French courts fined him €6,000, which he accepted without complaint. More interesting than his humiliation, to me, are the dramatic moments themselves: what purpose is served when he, or we, volunteer to watch them again. Melodrama, when it fails, produces embarrassment, which is distinct from humiliation or shame. It burns us, then it dissipates; it sears through a brief spell of time. The writer Gwyneth Siobhan Jones calls it “a pulsating hyper-awareness of being flawed.” That night, in La Perle, the bystanders were stunned, but they didn’t scream or knock Galliano down. Their momentary indecision — what should we do? — is typical. As Jones puts it, embarrassment appears as a “blockage of language leaving us tongue-tied, lost for words.” She terms it “an unspeakable feeling.” We try to reassert ourselves by converting it, through laws and codes, into verbalized shame.

You’d have thought that Galliano would’ve known how his performance would come across. He used to trade in how remorselessly art could reinvent everyday life, bringing out the underbelly of urban drama to ask what it was proper to stage, and what we were prepared to watch. One of his finest Dior collections was a study in melodrama, the Spring/Summer 2000 couture line. It was designed around homeless people and became known as the clochards (tramps) show; as with the Rose interview, you can still watch that show on YouTube today. Women stride down the runway in unstructured garments that are strangely layered and riddled with tears. A pin, outlandishly big, yokes a string vest to a belt: the belts are strung with empty miniature bottles and dulled, grubby chains. The models’ hair is threaded with tissue, and their faces are made up to look like they’re smeared with grime and sweat. Much of the collection is made from a silk printed with newspaper articles — the fashion pages from the International Herald Tribune — and the material is cut daringly on the bias, per Galliano’s usual technique, to lend these pictures of distress a perversely sensual air. A few years later, Galliano would take The New Yorker’s Michael Specter on a jog along the Seine, and show him the sans-abris whom he claimed had inspired that line. “There is,” the designer said, “this whole world of fantastic characters who live there, I believe through choice.”

That belief seemed characteristically untethered to reality, as it’s understood by almost everyone else, and the aftermath of the Dior show was as febrile as you’d expect. The house’s offices at 30 Avenue Montaigne were picketed by protesters, furious at Galliano’s “cynicism.” In the New York Times, Maureen Dowd’s response was not only representative but acidic: “Dior models who starve themselves posed as the starving.” (Which was a cute line, but in pursuing rhetorical drama — “starve themselves” — she was no more kind or thoughtful than the man she critiqued.)

I take Galliano as being honest when he said “I didn’t set out to make a political statement. I am a dressmaker.” But to think the two are divorced is naïve, not because “everything is political,” a neat but meaningless phrase, but because fashion is a public exchange of appearances that shapes our sense of self. Galliano’s notion of the inherent melodrama of clothes — which we all wear in each other’s eyelines, all day, every day — was clear in his admission to Rose that he couldn’t stop finding the world theatrical: “Pretty much anything I apply myself to is ‘on the creative way.’ I could be walking down the street and still my eyes [are] working. I am looking at people.” Nor is this picture of society wrong. As the art historian Anne Hollander wrote: “Dress is a form of visual art, a creation of images with the visible self as its medium…. People inwardly model themselves on pictures and on other people, who also look like pictures because they are doing it too.” You could argue that, by Hollander’s logic, the clochard collection was a political failure because its model of life’s visual drama was obscene: one party takes everything from another, with no hope of reciprocity, and then they flaunt what they have gathered in front of people like themselves.

Tasteless collections are embarrassing; more than that, they continue to be embarrassing; and they were already embarrassing long before Galliano turned up at Dior. In being so embarrassed, however, we’re reminded why drama has power at all. We’re returned to the peculiar social magic that constitutes a theatrical or artistic occasion — consenting to believe in people doing special, non-everyday things, making worlds and inhabiting them — and then we’re shown the point at which our tolerance for that magic breaks. Some people react by saying that it’s not our fault, it’s the magician’s: there are things, you must understand, that it isn’t appropriate to stage! Dissent from this is rare, and sells poorly — especially online — but Guy Trebay of the New York Times had a go in 2017, when Daisuke Obana produced a clochardesque collection at New York Fashion Week. Obana’s work, Trebay suggested (in contrast to most other critics), wasn’t cruelty or thoughtlessness, rather proof that “the glass of fashion is mostly a reflective device…[this collection] served as a reminder of an often invisible population.”

Fashion is an art form that shows what you didn’t expect to see, or perhaps didn’t want to; in doing so, it brings our self-possession into flux. As Colin McDowell writes in Galliano, the boldest couture is like any art: it “should ruffle our complacency by questioning not only our attitudes to beauty, femininity and allure, but also to ourselves.” And when those attitudes are being tested against others, our vulnerability to embarrassment is productive, a weakness we find we need. To pretend you’re immune would be arrogant, but more importantly, it couldn’t be true. From catwalk to street, we’re mesmerized in solidarity.