Here’s the opening act of Patricia Highsmith’s 1952 novel The Price of Salt: It’s Christmastime, around 1950. Therese Belivet, an aspiring young set designer who lives in a pocketbook-sized studio in Manhattan, has taken a temporary job as a salesclerk in the toy section at Frankenberg’s, a department store in Midtown. Across the counter, she spies the impossibly elegant Carol Aird, a suburban housewife nearly twice her age. Therese’s boyfriend, Richard, is fine, but she’s numb to him, physically and emotionally. Carol, on the other hand, arouses Therese. Carol leaves her address on a delivery receipt, and on an impulse, Therese sends her a season’s greeting card. Instead of using her own name, Therese signs as “Employee 645-A,” her Frankenberg’s identification number.

A dizzying courtship ensues, silhouetted by Carol’s acrimonious divorce proceedings and a hot-blooded road trip out west. You might say the novel is about female desire, lesbian romance, and sexual exploration. You might say it explores power dynamics, intimacy, and subverting societal expectations.

But it’s also a department store book.

The department store in The Price of Salt might seem like an arbitrary blank canvas of sorts, interchangeable with any anonymous urban institution where Therese could have temped to pay the bills. But the department store is not only a highly specific setting, it’s crucial: it compels you to become someone other than yourself. Reduced to “Employee 645-A,” her coded identification on the sales floor, Therese sheds any sense of fixed identity and leaves prior attachments behind. In the department store, she’s not only permitted to acquire and fulfill new desires — that’s what the space requires.

The Price of Salt begins not on the sale floor, but in the employee cafeteria. Therese is reading the “Welcome to Frankenberg” manual — or rather, rereading it. Meeting her here primes the reader for a classic upstairs-downstairs tale of ambition. Perhaps Therese is a plucky, working-class heroine, eager to rise through the ranks to become a well-mannered shopgirl. “Are You Frankenberg Material?” asks the manual, in giant glossy script.

But Therese has more aggressive ambitions. With true Main Character Energy, she’s reading only to avoid engaging with anyone else. The material is merely something for her eyeballs to cross, just as the cafeteria’s “gray-ish” roast beef is only useful for its nutritive value. She does want to move “upstairs” and become the client rather than a worker — but more than that, she wants to divest from the store altogether. Frankenberg’s is a waystation, not an endpoint. It’s one of her stage sets: she invests in this world, but only just enough, knowing it will soon be taken down.

Of course it’s not an easy gateway to pass. Like a stage set, Frankenberg’s is more symbol than reality. It’s the representation of commerce first, a place of commerce second. It’s easy to get lost, physically and psychically, in the metaphors. Take the shop windows: They might be mirrors, showing Therese as she is; they might be portals, glimpses of mannequins portraying who she wishes to be; they might be magic mirrors, taunting versions of herself that she knows she’ll never become. Then there is the doll Therese must hawk to customers: Drinksy-Wetsy, which features a rudimentary intestinal track for young girls to rehearse their maternal destinies. “The store was organized so much like a prison, it frightened her now and then to realize she was a part of it,” Therese thinks.

This awareness, though, is critical to the escape. If our heroine emerged from the dingy lunchroom and became intoxicated by the glittering fantasia of the main floor, there would be no reason to leave with Carol. Much better for the artifice to shine through, to arrive on the less-than-idyllic seventh floor, the toy department, where the ecosystems make a miniature America: trains, farms, suburban homes. You have to see the edge of your reality in order to pierce it.

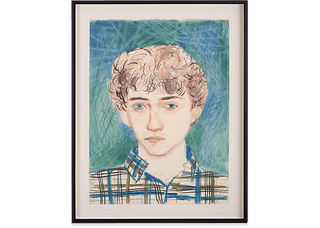

There’s some uncomfortable, but essential trial-and-error: Therese becomes a doll herself several times over, before finding her own form. The first time is a dress rehearsal, a Punch-and-Judy version, grotesque and all wrong. She meets an older colleague, Mrs. Ruby Robichek, who insists on fitting her for a dress. She stands semi-naked in Mrs. Robichek’s living room as the old woman fusses around her, but the scene isn’t at all erotic: “The room smelled of garlic and the fustiness of old age, of medicines, and of the particular metallic smell that was Mrs. Robichek’s own,” thinks Therese, covered in goose pimples even though the heat is blasting. She’s gone as numb and plastic as a toy designed to have clothes ripped on and off inelegantly by a child. Previously, the image of herself in the dress had captivated Therese. Yet she now feels a wave of dread, as a certain future flashes before her eyes: “It was the hopelessness of Mrs. Robicheck’s ailing body and her job at the store…” Therese expresses her apprehension in the language of the department store, but the fear extends far beyond the sales floor: more than getting stuck aimlessly floating in this job, she’s afraid she’ll be swept along in this version of her life.

Only when Carol enters the store can Therese find her escape: she might be in the same body, but she’s discovered her new identity. When Therese becomes a department store doll for Carol, she slides out of play-acting and into her life. Carol doesn’t want to dress Therese up — she wants to undress her. Therese’s Sunday visit to Carol’s New Jersey home is the mirror opposite of her dress-fitting at Mrs. Robichek’s. They drive on an empty road. It’s morning, and the weekend, and they’re alone in an enormous house together. There’s so much possibility ahead of them. Therese is free of Mrs. Robichek’s metallic smell and the glut of playthings in the commercial palace of consumption. It was just a matter of time and rehearsal. The patience to wait for the right future in the crowd of customers.

The department store has a long history as the locus of fantasy and lust, longing to be a different version of yourself. It’s no accident that many authors, artists, and directors — L. Frank Baum, Vincent Minnelli, Andy Warhol — got their starts as shop window dressers, designing tableaux to entice and allure audiences with seemingly magical displays, projecting glamorous yet seemingly attainable new versions of themselves.

When Sister Carrie, the eponymous heroine of Theodore Dreiser’s 1900 novel, first enters a department store, her magpie eye alights on all the objects — “Each separate counter was a showplace of dazzling interest and attraction” — in an orgiastic, unapologetic celebration of stuff. But her real ambitions turn almost immediately towards the shopgirls themselves: “She noticed too, with a touch at the heart, the fine ladies who elbowed and ignored her, bristling past in utter disregard of her presence, themselves eagerly enlisted in the materials which the store contained.” For Carrie, green, penniless, as-yet unjaded, becoming someone who could buy the baubles herself is so many levels removed from her worldview that her desires don’t even lead her there yet, but she can imagine herself as someone who might become part of this ecosystem by selling in it. Perhaps all our dreams are more incremental than we realize.

In fact, Highsmith published The Price of Salt pseudonymously as “Claire Morgan,” her version of Therese’s “Employee 645-A.” She didn’t want her name to be associated with a lesbian romance, fearing that, in the 1950s, she’d get pigeonholed and, more likely, blackballed. This might sound grim — a more-or-less imposed cloaking — but the name’s not without a glimmer of hope. A polyglot autodidact, Highsmith kept diaries in up to five languages, and the entries from the conception of The Price of Salt are in German. “Claire Morgan” is a near homophone of Klarer Morgen, or “clear morning”: the moniker’s at once an obfuscation of Highsmith’s identity and a fresh start hiding in plain sight.

And though Highsmith did choose to obscure her identity, she was not shy about the actual act of writing, of putting her life on the page. According to Highsmith’s diaries, the germ of The Price of Salt came to her all at once, in just two hours’ time, blossoming fully formed as “The Bloomingdale Story.” (Frankenberg’s, Bloomingdale’s, you say potato, I say potahto.) “It flowed from my pen as from nowhere, beginning, middle and end,” she recalls. Highsmith found inspiration from her very first moments in the short-lived role:

December 6, 1948. First day at Bloomingdales. Training, and then toy department. Very pleased.

December 7, 1948. Hard work. Selling dolls, how ugly and expensive! And then — at 5:00 P.M., someone stole my meat for dinner! What kind of wolves one works with!

December 8, 1948. Was this the day I saw Mrs. E.R. Senn? How we looked at each other — this intelligent looking woman! I want to send her a Christmas card, and am planning what I’ll write on it.

In The Price of Salt, desire is thus always in duplicate. Highsmith fills Frankenberg’s with slivers from her past: Therese works in the same department. Therese has her meat stolen from her. “E. R. Senn,” of course, becomes Carol. In this way, the novel becomes Highsmith’s own department store, in which she can transform her story into new dressing. She can become someone else.

Observing all the possibilities of the department store in literature, film, television, and art, I feel the loss of their real-life counterparts even more keenly. Macy’s are shrinking into “mini-markets”; the building that once housed the behemoth B. Altman, where newly single and plucky Miriam Maisel finds employment in The Talented Mrs. Maisel, is the CUNY Graduate Center. Barneys, the bastion of NYC luxury, is closed; department stores around the country have shuttered or become shadows of themselves. In Philadelphia, Macy’s occupies a scant three of the original twelve floors of Wanamaker’s, like a shriveled snail body cowering inside an elephantine shell. Today, The Price of Salt probably wouldn’t take place in a department store. I’m not sure where it would take place, really.

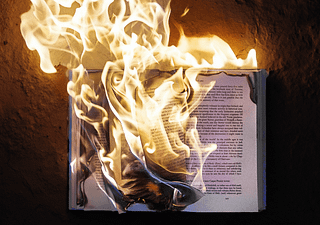

Maybe we need these spaces a little less. Queer desire no longer needs to be sublimated and hidden; lust can play out in reality. The disappearing department store might herald progress — after all, its artifice was hardly democratic or sustainable. Patricia Highsmith’s name appears prominently on the covers of the reissued books. Carol, a major motion picture based on the book, adapts the story in lush, warm tones for mainstream audiences, but without changing the lesbian romance or the storyline. Still, I fear that without this kind of institutionalized space for imagination, we’re also in a false utopia — repression remains rampant. And I miss the way in which the department store offered the freedom to play out all kinds of versions of yourself, to try on aspirational, or simply different, self-concepts. If the department store doesn’t exist, where will the next institution of the imagination find itself?