“Do you ever feel like we live in the least romantic times ever?” a Swiss diplomat’s daughter asks me, as she pulls out her bucket list for a “more aesthetic” summer (skinny-dipping, trespassing, a doodle in colored pencil). “I can’t help but regret that we live in the time of shopping malls and smartphones, and wish for something better.” She goes on to describe her parents’ Eurail adventures, how her mother “stumbled upon” the Berlin Wall and wrote about it in her letters. She doesn’t smoke but says she loves the aesthetic. When someone lights a Vogue with a match, her pupils dilate with admiration and she stares at them for a few uncomfortable seconds.

“I don’t understand why we aren’t all screaming!” my French environmentalist friend says to me one week later, after a long conversation about the world burning with her family in the eleventh arrondissement in Paris. Her uncle shows up to dinner in high spirits, asking us how we, as “climate-conscious girls,” feel we’ve fucked up in the past year by producing unnecessary carbon emissions.

I’m zoned out, looking at the crocodile hides on the wall of the restaurant, thinking about my steak that should be arriving any second. I try to brush off the question. But he repeats it, in slower French this time, and cocks his head to the side when I start laughing at it. While her uncle and I discuss the ethics of air travel, my friend picks at her mayonnaise eggs and falls silent. She’s in tears by the time we get back to her mother’s apartment by Luxembourg Gardens.

Two years ago, we sat on the floor in her bedroom discussing the ethics of having children when my friend articulated the ambitious idea that we could commit suicide, if we were really serious about reducing our climate emissions. Now she has a stack of flyers on the dresser, outlining various individual activities and their associated emissions. She says she’s in the mood to post them on the windshields of cars across Paris. Will I come with?

I’m not sure why I decide to make her cry harder. I tell her I love the French habit of drinking out of little cans on the street and announce that I don’t think art should aim to “change” anything, two days after she’s told me about her climate-optimistic speculative fiction project.

“I thought you were someone like me — someone who cared about the planet,” she says. “I understand now, you’ve become nihilistic.”

Sad about the ocean that my friend and I have discovered between us, I wonder if I’ve rotted my brain, supplementing Zoom university with politically disaffected ASMR noises, or if my European friends simply don’t get it.

The following week, I set up lunch with Roc Sandford, an island laird I first met two years ago who is involved with the environmentalist group Extinction Rebellion (XR). We’re eating quinoa and lentils in his townhouse in Kensington Gardens — Roc splits his time between here and the remote island he owns, without heat or water, in the Hebrides of Scotland. When we first met, we sat in the dark and discussed his love of Flaubert and how sublime it felt, the first time he was kicked in the face at one of XR’s performative protests. While our collective futures are still grim, the mood here is brighter — his daughter has recently come up from underground, where she was protesting HS2 railway construction, and now has a book out from Pavilion.

After lunch, Roc shows me his office: an enormous salon adorned with a tent and a bathtub, deranged stacks of books resting by it. In this room, Roc takes Zoom calls, helping organize an international network of climate rebels. Roc tells me about a protest happening in Lisbon, at the 2022 United Nations Ocean Conference, where a new group called Rave Revolution will be making its debut. Roc tells me I could be a mermaid if I wanted.

I decide to go. On this trip, “making friends with boredom” has been my personal mission. I’ve been telling anyone who will listen that “learning to lay about” is an important skill for any creative young person to invest in. But in the middle of a perpetual heat wave, the notion of spending hours in the park with a notebook, waiting for Haussmann’s architecture to inspire has started to feel stupid. “I hate summer,” a friend texts me, shortly after moving to Montpellier with a similar project.

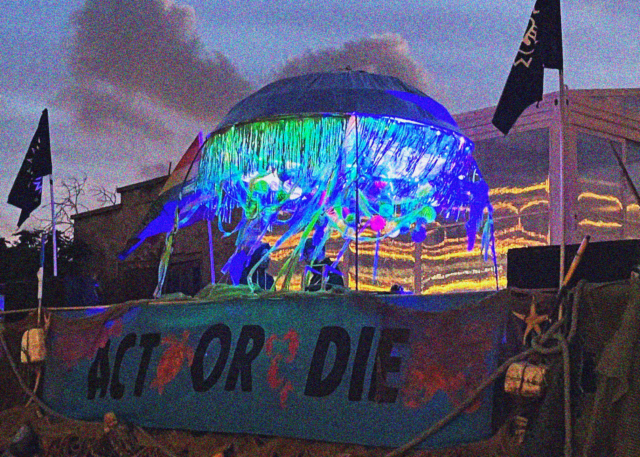

“On this stage, the greatest DJ in the world will play,” is the first thing I hear Tommy Diacono say, in a thick Maltese accent followed by a light cackle. When I first meet the founder of Rave Revolution, he’s wearing a muscle shirt and building a giant jellyfish umbrella for Rave Revolution’s first protest. In three days, this umbrella will be installed on top of a truck and a line-up of DJs will play under its shade outside the United Nations Ocean Conference. Dancers from around the world will surround the truck, dressed in blue, and sway in protest, calling for the leaders of the world to abandon GDP as a success metric. At night, Tommy’s plan is for the protest to morph into a five-kilometer march, with a rave at the end of it.

“We have to get dancers, who are semi-feeling beings, who are literally feeling the heat, to speak up about the climate crisis,” Tommy says, gesturing up to the sky and down at me, as if waiting for lightning. “The idea is to disrupt, but with beauty.”

We’re at Fábrica Braço de Prata, a cultural center that Rave Revolution is using as its base of operations, alongside Ocean Rebellion, an Extinction Rebellion offshoot that practices performative protest. While members of Ocean Rebellion are “rehearsing,” walking around in limestone fish head masks and debating whether the fake blood is red enough, the Rave Revolution volunteers are distinguished by complicated geographic roots, expensive-looking outfits, and an air of aloofness. Women from Milan, Portofino, and Berlin appear over the course of the day and watch Tommy cut jellyfish tentacles out of metallic fabric.

A “raver by blood” and a chef by trade, Tommy ran a chain of burger restaurants in Malta until the movie Cowspiracy made him woke about the climate crisis. The idea for Rave Revolution surfaced at a permaculture retreat, where Tommy met Emily Collins, a creator from Los Angeles who will later tell me she represents “the divine feminine.” Through an international network of friends in fashion, tech, and hospitality, the two raised $3,900 on GoFundMe for this first protest, which they supplemented with five thousand euro from the Climate Emergency Fund and a large donation from a wealthy Italian family, that Tommy says is “very nice” and interested in changing the system. Tommy and Emily decided to make their debut at the UN Ocean Conference because they have a lot of friends, and friends of friends, in Lisbon.

“He’s got a massive ego,” an Ocean Rebellion member says of Tommy. “He’s bridging the Maltese, hardcore mafioso restaurant world, as well as the party scene, mixed up with high net-worth individuals. He’s a case study of what transition looks like. It’s fascinating to see someone like him up close.”

Citing Burning Man and Woodstock as examples of the revolutionary power of experience he’s trying to harness, Tommy says rave is a good way to protest, because “with rave there’s a secondary message.” Dancing makes the discontent personal. “When people say, ‘oh, you’re here, just dancing and taking drugs,’ you can answer, ‘yes.’ You told my generation to go to school, go to school and educate yourself. I educated myself. Now the scientists are telling us we have twenty, thirty years left if we continue on this path. What the fuck am I going to go to work for if I don’t have a future?” Tommy takes a break from the jellyfish. “It’s a cool way of protesting , where you’re dancing and taking drugs in the street. It’s like a fuck you to the elders — we inherited hell on earth, it doesn’t work, so I’m going to rave.”

I join Rave Revolution’s Telegram chat that night, where the admin has sent a message comparing the night club to a temple, where strangers can join as ONE and wash away their differences. I’m not into rave and generally leave live music unimpressed by the experience, but I like Tommy and have another five days in Lisbon, so I try listening to “the greatest DJ in the world,” Dixon.

I sit on my hotel room bed cross-legged while my water-damaged iPhone speakers play EDM. I close my eyes and imagine how it would feel, to participate in a rave that mimics religious experience, to lose my inhibitions in a mob of strangers and demand sweeping changes to our political systems.

The next day, a stack of flyers appears at the base, printed in a pale pink and blue that reminds me of a Coachella advertisement. On Instagram, someone reposts the flyer with The Beatles song “Revolution” playing in the backdrop of it. I complain about the heat, Tommy stops spray-painting the jellyfish and locks eyes with me for a second. “It’s the coldest summer of the rest of your life — enjoy it.”

Tommy asks me if I believe in magic, while taking a swig from a bottle of mezcal in the half hour leading up to Wednesday’s protest. “Our energy comes from the sun,” he says. “Our consciousness is cosmic, so when you give yourself 100 percent to something that’s pure, you have these weird little things that happen.”

I woke up that morning to a video of Tommy’s hair blowing in the back of the jellyfish truck, and rushed to meet him at Altice Arena, an egg-shaped dome built for the 1998 World Exposition and the site of this year’s Ocean conference. I tried to get myself a coffee at the Starbucks across the street to hype myself up for a full day of protest, but the line was too crowded with NGO project managers and communication consultants.

At two, friends of Tommy and Emily start to arrive and pass the mezcal in circles. A photographer walks up to the site grinning and points to his water bottle as evidence of his commitment. A girl from Kazakhstan clutches an Elf bar (“I’m just really nervous”). Because of a miscommunication with the Lisbon police, the protest is happening on a side street instead of disrupting traffic at the center of the conference, as Tommy anticipated. “We’re beautiful, we do what we want,” Tommy says, before signaling for DJ Cole Trickle to cue the music.

I bop around and try to figure out why everyone’s here, what resonated with them about Rave Revolution’s message. No one gives me the depth I’m looking for, but I’m not dancing or on drugs, so the problem could be that I’m not speaking their language.

The protest is successful in the sense that conference attendees stop and stare, some join, grab a sign, and dance awkwardly for a few minutes. I talk to a few young locals who showed up merely because of the DJs, with no connection to the people behind the project. The President of Palau, evidently inspired by the dancing masses, asks his people to get him involved and gives a speech under the jellyfish about the effects of deep-sea mining on the Pacific Islands.

At 7:30 PM, when the crowd prepares to transition to the march, I meet Emily and Tommy at the accompanying truck. Preparing to shepherd the crowd on the ground, Emily crawls off the flatbed and, in an effort to keep me occupied, ushers me on top of it.

“There are very powerful people interested in climate reversal,” a man in a kimono says to me, learning forward seriously and yelling over Dixon’s set as the truck starts to move — Dixon starts blaring the bass, Tommy triumphantly smokes a cigarette, and Emily stomps around in oversized brown boots behind us.

In-between sets, I get my interview with Dixon. “Everything that can be done, should be done,” the German DJ says when I ask him why he agreed to play at the protest, in a way that sounds sincere but lacks urgency.

After about fifteen minutes, police surround the truck and we stop, plans for a five-kilometer march curtailed. Tommy tells us to get off the truck. I join the crowd as we wait for Ubers to come pick us up.

Did this feel different than a regular concert? I ask around at the after-party, where the rave is going to start as soon as they figure out the music.

“It’s partying for a purpose,” a Brazilian water therapist says, while passing around a Hydroflask filled with a tasty mango-pineapple alcohol beverage. “You’re in the location, so you try and raise the vibration.”

Few of the other environmentalist groups who were marching behind us seem to show up, at least not while I’m there. Instead, the people I talk to are an amalgamation of yogis, “experience artists,” twenty-two-year-old ravers, and tech company founders, who, despite coming from different corners of the world, all seem to already know each other.

For a brief moment, I catch Emily. Having previously worked with nonprofits and in corporate finance, she says she’s finally found her place “in the global politics arena,” through Rave Revolution. She runs away to take a self-care break before I can ask any follow-up questions.

Do you need food? Do you need water? I ask one of the volunteers, who’s been trying to get me to dance all day. She’s started telling people she’s from “the capital city of Deutschland” (“I’m sick of saying I’m from Berlin.”) She won’t tell me what drugs she’s taken, but she alternates between saying “I need to sit down,” and walking around the lot, giggling. At this point, I’m weary of the self-satisfied atmosphere the spliffs are creating, or maybe I’m just envious of this scene I’ve peered into, of well-dressed strangers floating around the world confident they are carrying love in their heart for all living beings, without an inner monologue to keep them company, tallying up all their hypocrisies.

Before I leave, the girl from the capital city of Deutschland gives me a prop she’s made, a starfish taped onto a purple headband. If I want to rave in Berlin, she says, I’ll always have a place to stay, because we’re friends. I say goodbye to Tommy and ask him if he’ll help me figure out how to camp, if I ever want to go write about Burning Man. “Anything,” he says, and I leave the party with my headband, kind of sad, knowing I’ll never talk to these people again.

The whole time I was in Lisbon, flanked by the ocean and some architecture that’s supposedly interesting, I couldn’t stop thinking about the rats in New York City. When my Swiss friend complained that we live in the least romantic times ever, I didn’t tell her what I felt I was discovering in New York. How it’s here, exploring the spots where the city feels most like a sewer, rabidly scrolling through my phone on the train and dressed in something I picked out carefully, that I’ve felt the most honest and at one with humanity. She’s texting me from a nudist beach.

I fill the week of my return with activities my friends will make fun of me for, for always wanting to do the “scene-y thing.” On a Tuesday I go to a play. In one of four stories unfolding in an apartment in Berlin, an American journalist gets annoyed with his date for refusing to employ “the slightest bit of irony” in their romantic exchange. The German girl replies, “Does it bother you that I say what’s on my mind?” When my friend called me a “nihilist” in that bedroom in Paris I felt terrible. I had to do this whole reporting project to find out if I’d been infected by something evil. After the last act, the play floats to a bar. When I end up on a trampoline with the actors who the roles were built for, I feel free, knowing that I no longer have to worry about the opinions of people who think they are being honest when they are projecting an ideal of their own purity.

In the West Village later that week, I go to a one-woman show where “the most well-known unknown” actor in New York recounts tales of her unhinged-aspirational lifestyle, ambling around and chain-smoking south of Houston Street. I recognize entire monologues from her Instagram and find myself feeling cheated by the person on stage. I am put off by the idea of her “rehearsing.” I need a new invention from her each day. I need to know that no matter what, she’ll be razing her vagina in her dates’ dirty apartments and vaping furiously, to keep the story going. I bet she’s exhausted. She looks amazing, wearing a white dress that falls on her waist perfectly.

Because the temple of raving doesn’t resonate with me, in New York I’ve fallen into another kind of haze, this idea that life is a stage. If you can pick your own avatar, inspire a vision of how exciting life could be if you made everyone talk to each other, mold your friends into characters that suit them better, it doesn’t matter what’s actually in the water. My godfather says it sounds like a “narcissistic power trip” when I describe this mode of blending life and art together.

I get lunch with my friend in the heart of the scene — as if that meant something. When we sat down, it felt like we were only half alive. We didn’t ask many questions about each other. We were mostly thinking about the image that would come after. After we paid, my friend walked to a spot where the bridge unfolded behind us. He handed me his phone and asked me to back up.

In Lisbon, a raver from Italy told me he’ll be dancing until we’re all dead. I guess I’ll be taking pictures of my friends. I like this better than screaming, but I just started and I can already see the end.

It’s the first week of August and I’m perched over a red tablecloth at a restaurant on Spring Street, waiting for chili. My friends and I are talking about how hot it is, how the heat makes you less hungry. They’re talking about the people at work they think are annoying. I tell them about the climate rave I went to in Lisbon and the piece I’m writing, and ask them the questions that have been bothering me.

My friends can’t give me a justification for sitting pretty, apart from the fact that screaming “would be cringey.” Then they order another round of martinis.

I’m bored. I’m trapped in the corner seat and I think the server forgot me. I’m hungry. It’s August. I don’t know why I thought I wanted chili.