In the summer of 2020 sunlight began to repulse me. The toxicity of the smoke-filled air in Melbourne meant that sometimes you weren’t allowed to leave the house. These were days of obsessively watching the news, of gasping before footage of marsupials fleeing their habitats, of townsfolk taking shelter on the beach while everything they owned and loved dissipated in an instant. But the next two summers didn’t play out, as one could have reasonably expected, in the sullen shade of their predecessor. Rather, in both 2020 and 2021, the intensity of extended winter lockdowns gave way to summers of reckless abandon, the spiritual impoverishment of the populace unlocked by lower case numbers. There was an unfamiliar permissiveness in the air, and it seemed as good a time as any to stop caring and just go for it. When January 2022 rolled around, nobody was willing to glance back to the hellish summer of two years’ prior, because nobody wanted to be the one to put a dampener on the party.

Neither was I too interested in looking backward. I was gearing up for a move to Paris, which I made in the middle of that month. Though I was leaving people who were at last indulging in a quasi-mythical period of newfound liberty, I perhaps wasn’t asserting such a distance after all. Mine was just as much an exercise in myth-building as theirs. The difference consisted in my forsaking the iconography of Australian summer — flattened magpies on the highways, cheap jugs of Melbourne Bitter, bodies splayed on the beach for a golden hour that never ends — for a more grandiloquent continental fantasy, involving trench coats and rain-dappled cobblestones veiled beneath endless reams of mist. Easier to justify locking myself up in an apartment somewhere and working when it was near-zero outside. But then, what was to happen to this self-image when the mist dissipated, replaced by shards of scorching light? By May I had come to realize that not only do they also have summer in Europe, but that there was an entire way of being in summer that centered around the irrepressible allure of the Mediterranean, a concept far vaster than the bounds of its sea. When Parisians began heading south for their summer escapes, I asked myself: shouldn’t I, as a fellow resident of Paris, head south too?

Never mind that I was simply exchanging one fiction for another. The offer I received from a friend to rent her Montpellier duplex from the beginning of June to the end of August was, even with my reservations about summer heat, too compelling to resist. Or more precisely, the images that the offer brought forth were so overstuffed with fictional luster that I found it impossible to deprive myself. Contempt, Elena Ferrante, Claire’s Knee, Dick Diver, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, Charmian Clift on Kalymnos. I pictured myself strolling the cream-white streets of towns whose buildings dated back to medieval times, drinking bottles of chilled red wine, reading books in the shade of the olive trees while a cigarette dangled irresistibly from my lips. The images, of course, were to act as a kind of entryway. Maybe if I inhabited them deeply enough, I could obtain the sense of sophistication, assured self-regard, and unfettered independence they suggested. After all, it was more than just a visual fetish; in coalescence it formed a concept, a complete worldview whose every end was neatly tied. It was called The Mediterranean Life, and it was going to be mine.

Almost immediately after relocating south, I traveled to Venice to check out the Biennale. Yet, as I traversed the stone bridges and light-flooded campi, I was surprised by the appearance of certain seams in the myth. Expecting the luminous and floating marvel of Visconti’s Death in Venice, I instead found a city whose colors were fading in the unrelenting sun, and whose waters looked like bile. Even the Biennale felt wayward, its crassness of spirit and deep-seated irreverence seeming unworthy of a city that had just turned 1600 years old. My days weren’t passed in slack-jawed reverence but in uncanny perplexity, bathed in sweat. I couldn’t recall ever feeling so swamped by heat. The city’s flaking walls and hard stone streets, completely devoid of foliage of any kind, seemed to swallow up the diffuse sunlight and intensify it, like a prism in reverse.

One balmy morning, I was meandering by the Gallerie dell’Academia when a gondolier thudded into my shoulder. I turned back with an accosting look, anticipating an exquisitely Italian altercation. But he kept on, as if nothing had happened. I then noticed a few words stitched into his shirt collar. “Enter the dream,” it read in elaborate cursive script. But what, I asked myself, were the true terms of the exchange? Why was I the only one hunched over in a sliver of shade, gasping for air? Was that Serbian couple really enjoying a spritz by the Ponte di Rialto? Could that Korean family really be amused by the feeling of ice cream melting over their fingers? Hadn’t they seen the shirt?

When I finally left behind the dream of Venice, that nascent feeling of revolt remained. M., my girlfriend, had now joined me in Montpellier, and something about the environment suddenly felt dissonant. It was just as hot as when I’d left, only the trees were now that little bit more weathered, the grasses that little bit browner, the sighs of cooling winds that little bit rarer. I would regularly visit the local antiques market, held every Sunday beneath the city’s magnificent 250-year-old château d’eau. But as temperatures rose each week, the traders would spend more and more time camped in the rear cavities of their vans, peering out from the shadows, empty water bottles piling up beside them. Their irascibility made me anxious, and eventually I stopped going. Yet another element of my Mediterranean summer which no longer felt possible. The thought of wine was enough to make me sick, and it was definitely too hot to smoke. Where I could have been watching La Piscine or reading Lawrence Durrell, I instead binged the newest season of Too Hot to Handle — oy vey! — because the concentration required for anything more substantive was decidedly beyond me. When the season finished, I was bereft.

It’s difficult to imagine that Parisians feel this dejected as they pull into their converted Provençal farmhouses, or open the gate to their cottages on the hilltops of Sète. But then, their world isn’t a LARP, or if it is, it functions differently. That entire industries are devoted to the perpetuation of The Mediterranean Life is excusable enough — it’s not exactly the most malignant myth on the market. But there are many impressionable outsiders who, refusing to believe in any distinction between a life imagined and a life enacted, find the self-evident superficiality of the myth to be scarcely a problem at all. People who think in exclusively propositional terms: if you decamp to a summer house near the coast, like other native residents, you move from the outside of a culture to the inside. People like me, for example.

Suddenly, the emptiness of a certain narrative I’d superimposed onto my life was revealed. But that didn’t mean I was ready to give in to quiet defeat: M. and I decided to go to Barcelona. It was at or around this time that the first anecdotal reports of a continental heatwave were being seconded by the data. Okay — so perhaps it had nothing to do with the myths I was appropriating. Perhaps it was more my aversion to sunscreen (it ruins my skin) or my girlfriend’s hyperborean heat sensitivity (she’s Swedish) that explained our malaise. Perhaps this was just an outstandingly hellish summer. I texted a beach-loving Italian friend of mine to see what she had to say about things. “Europe do be having huge canicule vibes this summer,” she replied, and I thought: yes, it’s not just me. Everyone’s feeling it.

But seeing the Sagrada Familia appear as if quite literally melting before our eyes, scurrying to find a shady bench at Parc Güell, drinking beers that turn warm after five minutes, I had to ask myself: who gives a shit about the vibes? I’ve never liked warm beer, and I’ve never cared for sunburn. So why am I pretending? What is it all for? Well, I suppose it was for the dream, the same dream the gondoliers were selling in Venice, the same dream I’d sold myself. I was meant to have transformed from tawdry bumpkin to uomo di cultura; but instead, I found myself standing on the old hilltop battery overlooking the Barcelona basin, sweat pouring from my brow, feeling as bereft as ever. And so, looking out over the azure glimmer of the Mediterranean, I decided to embrace the nascent inklings stirring within me. I decided, once and for all, that I hate summer.

Or did I simply hate that I had been fooled? The sun didn’t force me to watch Too Hot to Handle, nor was it the Mediterranean that transferred the rent money to my friend from Montpellier. I was the one who had entered the dream. Perhaps I would have done well to listen to those who know better. Since antiquity, the Greeks have displayed an awareness of what you might call summer’s double-nature. For them, the hot months not only signal bounteous fields, fruits reaped, long outdoor lunches, but equally suggest the potential for destruction, as represented by Notus, the god of the southern wind, who is summoned by Zeus to rouse a devastating storm and cleanse the earth.

My Mediterranean Life lasted barely a month and a half. A mere week after stumbling around beneath Gaudí’s drooping architecture, I was in Denmark, where there were no olive trees, where the sky was a constant dull silver, and where the buildings, gray and brown and pale red, sat heavy in the empty streets. Crossing the old stone footpaths on our way to Marmorkirken, I noticed how right the cobblestones appeared in soft light, a touch of dew hovering around the scene. (In Montpellier, each stone reminded you of the blistering hot dragon egg in Harry Potter, except instead of offering a delightful newborn creature their gift was a third-degree burn). I looked up and saw the church itself, imperious yet ethereal, standing firm in a square completely devoid of gawking eyes, ice cream stands, sound, bustle. And later that day, when we took the train to our accommodation, about an hour outside of the Copenhagen city center, I found myself catching the dusty, warm scent of home fireplaces burning, even in the middle of July. “I’m in love,” I said, turning to M.

But the day we leave Copenhagen, it’s 28 degrees (82 F), and humid as all hell, and I can’t believe it. The central station is brimming with Danes too hot to care how much a cold brew costs at Espresso House. We board a train headed for Stockholm. Two hours into the trip, we stop at a small town where, after remaining stationary for ten minutes or so, the air conditioning stops blowing. The train begins to overheat, and we don’t seem to be moving. Disembarking to see what the fuss is about, I’m greeted by the solemn faces of three attendants, dressed in oversized white polos, black trousers, and thick work boots, who inform me there is a grass fire somewhere down the line which has compromised the train’s energy provision. All of a sudden it’s 34 degrees (93 F).

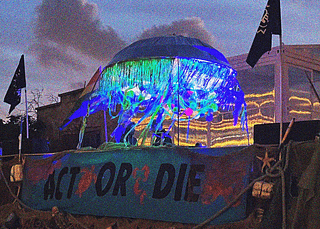

Over the next four hours, all of us are shocked to find we’re no longer in Asgard but Arcadia, forced to look into the eye of Notus’s storm. The train’s water supply runs out after an hour, people begin fainting after two. Confusion over why exactly we’ve stopped, and for how long, escalates the already palpable tension between the overworked attendants and the hapless passengers. “You know,” a birdlike attendant says to a particularly irate German woman, “if there’s no electricity, there’s no trains. Trains run on electricity.” Eventually the nearby convenience store sells out of all their refrigerated drinks. People take shelter in the slightly less-exposed station underpass, fanning themselves with old newspapers, while the desperation for this hellish summer to be over only grows.

When we finally get going again, the interior of the train still suffocating, the vision doesn’t cease. We’re rolling slowly along the track beneath a sky which, to our left, looks cloudy and pale, and to the right, is so uniformly painted with a smoky haze that my mind can only think of those days in Melbourne, that particular shade of black the sky took that summer, and the ubiquitous scent of slow burning that I’ve been smelling ever since.

Perhaps the events of January 2020 explain more than a significant part of this story. It remains one of my final memories before the pandemic began and the world shrunk down to impossibly mundane proportions. The smell of charred eucalyptus is embedded into me so deeply I can’t imagine what it’ll take for me to forget it. In Bronze Age Anatolia, the Hittites were known to refer to their king as “My Sun;” the Incan idea of heaven, loosely translated, refers to a “gleaming abode of the sun.” But I’m not sure I can accept a steadfast belief in sunlight as a portent of splendor and plenty. In the end, it’s just another myth — one I left lying somewhere on the ashen streets of Copenhagen, my very own gleaming abode.