1. I am not a Godard expert. I don’t get personally involved with celebrities — don’t follow them on Twitter, don’t know much about their lives. Identification is the mode through which so much art is offered to us. I find it a suspect mode, likely to slip so much sub rosa via the lie, they’re just like you! But I cried when Godard died. Not all-out howling, just tears gathering until they spilled over the brink of my lower lids. I did it until they stopped. I couldn’t stop voluntarily, and I didn’t quite know why. What was it that engaged me about the life and death of an artist whose work I know well, but who I also know may have had no sympathy for me, and whom I might not even have liked if we met without the protective interface of the screen? These were not sentimental tears and Godard was not a sentimental filmmaker. Like Godard’s movies, my tears might have addressed something structural.

2. Godard once described his film Breathless (1980) as “The story of a boy who thinks of death and of a girl who doesn’t.” But in the movie, Godard shows Jean Seberg (the young woman) thinking a lot. She sits by the telephone in a bar, thinking about whether to betray her lover (Jean-Paul Belmondo) to the police. He has killed a cop. All you need for a movie is a gun and a girl, Godard said (though multiple sources and Godard himself attribute this expression to D. W. Griffith). So Seberg betrays Belmondo and he is shot trying to escape. The original treatment of the film was written by Godard’s then–close friend, the director François Truffaut, but Godard “completely modified the ending. In my script, the film ends with the boy walking along the street as more and more people turn and stare after him, because his photo’s on the front of all the newspapers… Jean-Luc chose a violent end because… he was in the depths of despair when he made the picture. He needed to film death, and he needed that particular ending.”

According to the auteur theory that Truffaut proposed in A Certain Tendency of French Cinema (1954), the director is the locus of creative power. Godard fell out with Truffaut in 1973. Truffaut had turned to a more commercially acceptable style of moviemaking. He had, said Godard, betrayed cinema. He no longer told the “truth.” Godard would make a film that exposed the truth of moviemaking as the work of not only the director but of everyone involved. Truffaut’s expensive, mainstream films were, as Truffaut himself defined them, “trains that pass in the night.” But without the radical politics that Godard accused Truffaut of abandoning, his train “might be the one from Dachau-Munich.”

Truffaut wrote back, telling Godard he was “behaving like a shit” and, what’s more, he was the liar: only a lack of money prevented him from using star actors, and Godard had asked Truffaut for money to back his new film. Above all he accused Godard of disappearing from the scene of real-life politics. “Like Ursula Andress, you appear for four minutes, just long enough for the paparazzi, offer two or three shocking phrases, and then disappear, returning to advantageous mystery.”

On September 13, 2022, Jean-Luc Godard, suffering from “multiple disabling pathologies,” as his legal advisor Patrick Jeanneret confirmed, took advantage of his native Switzerland’s legal euthanasia. There was no mystery about this, said a family friend (who knows who?) to the French newspaper Libération. “He had taken the decision to end things. It was his decision and it was important to him that this was known.”

Godard, reports Liberation, had often thought of, and once attempted, suicide earlier in life. But his death was carefully thought out. To say that self-euthanizing was an auteur’s final cut would be an easy cliché.

3. The artist Robert Luxemburg found a still of Godard and his third wife, the filmmaker Anne-Marie Miéville, on Google Street View. Yes, it happened! Or so the screen tells me. Though who knows who picked them out from any other elderly couple on the streets of the small Swiss town of Rolle. From it, Luxemburg made a short and beautiful, melancholy movie that says almost as much about contemporary media as Godard’s 2018 The Image Book. The colors echo the stark Eastmancolor of Godard’s early movies; the classical soundtrack is lifted from Contempt and has a similar effect: the lushly formal music foregrounding the cold eye of the lens. The “camera” pans across the still (as Godard’s did in several movies) until, as in Pierrot le Fou, it comes to rest on an uncomprehending clear blue sky.

Like everyone captured by Google Street View, Godard’s face has been blurred. Miéville is already facing away, protected by her hair.

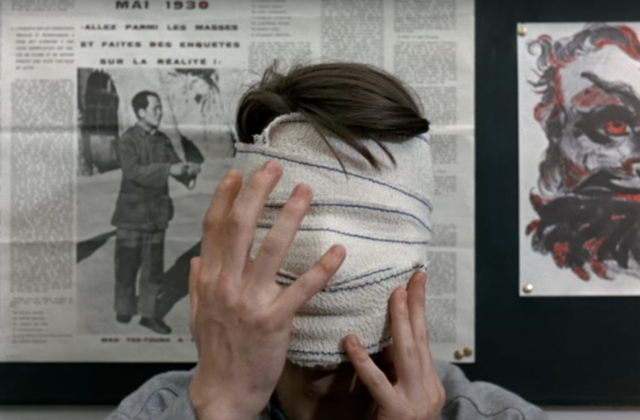

In the movie La Chinoise (1967), Godard regular Jean-Pierre Léaud slowly wraps his face in bandages while telling the story of a group of Chinese students who protested in front of Moscow’s Chinese Embassy. One student, whose face is entirely bandaged, shouts, “Look what they did to me!” When he removes the bandages, revealing no scars, Western journalists, hoping to see “a cut face covered with blood,” are outraged by his deception. Guillaume (Léaud) says, “They hadn’t understood. They didn’t understand it was theater. Real theater. Reflection on reality. I mean, like Brecht or Shakespeare.”

When I search Google Maps for the street where Luxemburg’s image was captured, I find that Godard and Miéville have disappeared.

4. I am not a Godard expert: but who is?

Only Agnès Varda ever got him to take off his habitual dark glasses, in The Fiancés of the Bridge Mac Donald, a short that forms part of her full-length 1962 film, Cléo from 5 to 7. It stars Godard and his first wife, Anna Karina, in a silent-film pastiche. Godard, white-faced and Keatonesque (or resembling that other twitchily gestural actor he directed so often, Jean-Pierre Léaud), courts dolly Karina only to see her fall down in the street and loaded into a hearse. Godard cries silently until a street vendor lends him a handkerchief. When he takes off his glasses to wipe his eyes, he finds Karina alive again: “My glasses made everything look black!”

Varda’s 2017 documentary Faces Places is a film I am unusually uncomfortable with amongst her works. The director enthusiastically follows an artist who pastes building-high photos of ordinary people in public places, with their occasionally queasy consent; some are not happy to see what he makes of them at cinema-screen scale. Late in the movie, Varda suggests they visit Godard. They are nearby and she hasn’t seen her friend for years. When they arrive, they knock on his door to no response. They find a cryptic note on the window:

à la ville de Douarnenez

du côté de la côte [the title of one of Varda’s films]

“Not very funny,” says Varda. And not cryptic. Godard had sent her the same short line — “à la ville de Douarnenez” — after the death of her ex-husband, Jacques Demy. La Ville de Douarnenez, a restaurant where the three filmmakers ate together. Varda looks on the edge of tears. “If he wanted to hurt me, he succeeded.” In response, she writes lines from the French nursery rhyme, “Au Clair de la Lune.” Flipping the gender of its innuendoes (doors, candles, pens…), she takes the male role, waiting outside, asking to be let in:

Prête-moi ta plume

Pour écrire un mot,

Mon ami Jacquot.

Merci, JLG,

De l’avoir de la memoire

Et pas merci d’avoir tenu

La port fermée

Lend me your pen

To write a word,

My friend Jacquot.

Thank you, JLG,

For having a good memory

And no thanks for keeping

The door closed.

Clair means light but it also means clear. Godard used the word in his film La Chinoise where he invented the Cinemarxiste slogan, “Il faut confronter les idées vagues avec des images claires.” We must confront vague ideas with clear images. Or maybe he meant light here, too. Light is essential for cinema: for filming, for projection. As is lightness.

Most people I’ve talked with about the scene in Faces Places see it as evidence that Godard was a shit. But it was Varda who staged the encounter, and filmed it. Who is wearing the dark glasses in this scene? And who is seeing blackly? It is a story about a woman who films the truth this way, and a man who doesn’t. It is a supremely moving moment. It may or may not be “truth,” but it is cinema.

Varda died in 2019. In Varda, in Godard, we have lost two unique ways of seeing. When I go back to Paris next month, I will find the city diminished, knowing neither can see it through their lens.