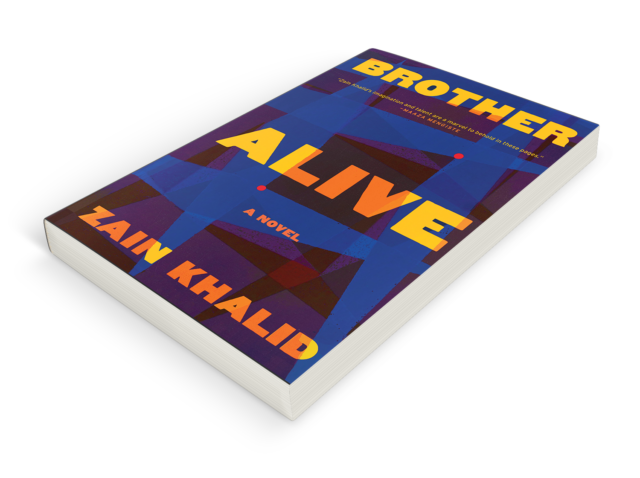

Brother Alive

Zain Khalid

Grove Atlantic, $26

Brother Alive nominally takes the form of a letter, although that premise is easy to forget. The first section spans nearly one hundred pages and twenty-odd years. The narrator, Youssef, recounts to his niece Ruhi memories of a youth spent in a Staten Island mosque as one of a trio of adopted boys raised by the charismatic Imam Salim. The origins of this unconventional family are a mystery: “Dayo, Iseul, and I were born in that order in 1990. That is true. What came next is not so much true as what we were told.” They were told little.

Much about Youssef is indeterminate, undefined. Yet his voice is crystal clear — knowing, sardonic, attuned to the political and suffused with the subtle charm of one who has read too much. Youssef, or rather, Khalid, has a knack for presenting the world at an angle. Describing Salim’s strange parenting style, he writes:

Our hair was not encouragingly tousled; our backs were never patted. For a high test score, we received a congratulatory gaze. In the event an embrace was required, he held his breath. And because Imam Salim’s expressions and mannerisms had to replace his touch, they became lovely to us. First his cheeks would moon, tapering his eyes into slivers of warm honey, then the wrinkle that rang along his forehead would deepen in apparently serious consideration, and, finally, all his straight-for-an-immigrant teeth would appear, slowly and softly, like a piano being played in the dark.

Khalid’s prose is often this precise and sensitive, his sentences taut yet full. The care with which he describes Youssef’s young life — its love, as well its injustice — holds the reader’s attention. Yet domesticity is not enough for Khalid, nor for Brother, Youssef’s bewitching “pest,” a shape-shifting creature invisible to others, “looming like a question in [Youssef’s] periphery.” Whatever Youssef feeds his “leech,” he himself loses: “I was able to rediscover some things I fed to Brother, like the name and taste of an apple, but much has been permanently lost.”

Brother is fascinating and grotesque, a sieve of memory with his own interests and attitudes. Not only does he inject doubt into Youssef’s reality, setting him apart from the “objective, documented, dull truth,” he comes to influence the story’s telling. As Youssef tries to control the creature through literature, “force feeding him inwardness or structural exteriority,” Brother recoils “from the dreck public schools teach indigent children … the state-sponsored writing about foils and masters and victimhood.” Brother looks askance at various narrative forms, keenly aware of what they try to evade and who they seek to control. Meaning itself is suspect. Adolphina, one of the boys’ caretakers, echoes the scholar Hayden White’s contention that the narrative impulse is often a moralizing one.“What regular people want,” Adolphina explains, “the essential thing, doesn’t exist. Is it meaning? Am I talking about meaning or is it virtue?”

Brother Alive’s first one hundred pages are truly delightful, its myriad layers ripe for deep and pleasurable reading. The sensitive yet exacting prose delivers a richness of character and setting, fueling a narrative that runs smoothly yet remains self-conscious of its undertaking. It is hard not to be swept up by a novel that works so well, on so many levels, particularly when Khalid dangles the lure of plot: How exactly did this family come about? What answers lurk behind Salim’s locked office door? Why all the secrecy, the lies?

Upon departing for Saudi Arabia, the land of his religious education and his sons’ birth, Salim leaves a letter that explains everything. Presented as one long chapter, it hums at an enticing pace. There are some lapses in Khalid’s craft — characters made flat through their seemingly boundless generosity, moments of overly explanatory dialogue — but the novel’s second section shares the merits of the first, this time with plot (as opposed to character) as the book’s principal engine.

But just as Khalid has answered our questions and primed us for some great caper to begin, the narrative sputters, then stalls. The brothers, having followed Salim to Saudi Arabia, find they have been hired to work on the “Brij” project, a “catalytic mechanism linking our societies to the world” evidently based on Saudi’s real-life Neom, a futuristic playland for the global elite intended to rival Dubai. They are at turns enchanted and repulsed. Devoid of motivation, they shuffle between bureaucrats, businessmen, and glorified bodyguards who describe their involvement and their politics in long and droning dialogues. Salim tries to recruit the brothers to overthrow the influential, liberal Sheikh who is responsible for both Brij and their family’s suffering. But, beset by ambivalence, the brothers cannot seem to decide who or what they stand for. Ought they join Salim in avenging their parents’ deaths? Shrug. Should they commit to developing this capitalist, Islamist utopia? Maybe. “You have no idea why you have come, do you?’” asks Sheikh Ibrahim, nearly three hundred pages in. They do not, and neither do we.

While the brothers are rendered impotent by Saudi prosperity, Brother grows strong. “Ever since we landed,” Youssef observes, “his body had become less spectral, filling in like a final sketch. Naturally this newfound heft required more sustenance.” Brother is newly immense and ravenous, demanding much of the ailing young man who once “held his reins.” Words will not suffice. Brother lures Youssef to the desert, swallows him whole and asks to be ingested in turn. In turns, Brother takes over the narration. He becomes, as Youssef describes him early in the novel, “a near-constant proof … that in our world the simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth — it is the truth which conceals that there is none.”

Resigned to a reality of no meaning and no virtue, the novel splits into two dispiriting threads — that of the wavering brothers and the emboldened, nihilistic pest. Yet there is a curious distance between these events, a lack of awareness, in Youssef’s telling, of how one might affect the other. We understand, even if Youssef does not, that Brother is disrupting the narrative logic. His growing strength is presumably the cause of Youssef’s accelerating weakness and the lapses in consciousness that interrupt the story’s once-steady flow. Whereas Salim’s letter took the form of a single, hundred-page-long chapter, Youssef’s telling is fragmentary, broken down into thirty chapters across a similar span of pages, time moving in irregular intervals, the line between dream and reality increasingly blurred. Youssef walks into Brother’s mouth and the story flits to “an imagining rooted in memory” of a childhood attempt at running away. In it, Brother attacks Iseul, and when Youssef awakes he has no memory of his sibling’s existence. In a turn both abstract and allegorical, Youssef depicts an attempted exorcism of Brother through a surreal scene of children torturing an animal. The novel’s first book was also split into numerous chapters, but they retained a linear logic, accruing chronological meaning. Here, these fragments seem to work in opposition, pulling Youssef’s reality, and the story’s fabric, apart.

One might simply attribute this narrative dissolution to Youssef’s physical and mental deterioration. But I struggled to understand this choice, to maintain my enthusiasm for the novel as its momentum slowed, the brothers aimless yet Brother increasingly alive — a chimerical spanner in the story’s once-smooth works. Ought we read the novel’s final sequence as an attempt to reject the norms of narrative storytelling, to flout the expectations of the novel? Or is Brother Alive simply faltering on its own, traditionally novelistic terms?

The novel — that tricky form J.M. Coetzee once described as “the sort of vehicle one would expect Europe’s merchant bourgeoisie to invent in order to celebrate its own ideals and achievements” — necessarily establishes expectations of narrative and character, ones that the author must either refuse or fulfill. There are many potential approaches. Clare Sestanovich recently examined our collective fatigue with the plotless, interior novel. “So much literary fiction seems intent on flouting, if not entirely flattening, conventional narrative arcs,” she writes, “About those high-brow, low-plot novels, the Amazon reviewer complains: nothing happens.” It’s hard to imagine making such a complaint of Brother Alive. Even in its late, confounding pages, a whole lot happens.

One might read Khalid’s turn away from narrative as a bold departure, an experiment in form. Perhaps he is enacting Jane Hu’s proposal to depict “capitalist totality and its impossible forms … through incommensurable shards.” It is clear that Khalid’s interests range towards the experimental. Among his influences he cites philosophers, filmmakers, musicians, and visual artists, alongside writers best known for their formal experimentations, from Percival Everett to Jesse Ball and Elias Khoury.

It is Khoury, though, who interests me most, in part because White Masks, Khoury’s 1981 book about a postal worker’s murder during the Lebanese Civil War, receives several mentions in Brother Alive. It is one of Salim’s favorites, an “elliptical” novel which kept “his mind from doing what the novel did so well.” A writer characterized by “the grand swirling of characters, the digressions and stories within stories, the lack of resolution, ” Khoury once called White Masks a novel about “disintegration rather than construction.”

This formal approach has a political valence. “Descriptive realism,” Edward Said argued, “established the narratability of events and characters … a consolidation of ‘national’ life, rather than as an alternative to it.” By contrast, “formless” works, as conceived by Khoury, are “temporarily freed from prescription, moral imperative, official consciousness” and free “the Arabic novelist from subservience to the novel as a European institution.” The refusal of narrative is, in a way, a refusal of the state, of the West, and of novels that in their calculated coherence serve purposes other than the truth. Khalid, in a recent New York Times feature, articulated his desires for his debut: “‘I wanted to collapse the distance between the facade and the plumbing.… It’s not an answer to anything, I simply want to give voice to the reality.’” It would seem he and Khoury share similar aims.

Yet while the experimental impulse is alive in these pages, Brother Alive ultimately lands in a perplexing middle ground. The enigma of Brother and his impact on the story’s telling, seems somehow extraneous, and the premise of Youssef’s letter — a structure that lends itself to experiments with time and tense, disclosure and evasion — feels inadequately explored. While one can sense throughout the novel a resistance to the slam-bang finish, Khalid delivers something of an action-movie ending, with the brothers turning the tools of the Saudi state back on itself, its neatness undercut only slightly by Brother’s final control of the narration.

One can feel, in Brother Alive, an urge to shatter the coherent world and let us examine its parts, with all their jagged edges. Yet this urge is coupled with a countervailing impulse to reassemble, to reconcile reality to narrative. Perhaps Khalid’s challenge is solely that of chronicling a dismaying status quo, that of malaise rather than resistance. An attempt to depict Americans who reject their country, yet remain insulated by capitalism’s physical and ideological comforts. “You have layer upon layer of distraction isolating you from the murder that goes into a television bought on Cyber Monday,” reprimands one of the several powerful men the brothers encounter in Saudi Arabia. “Here, economics are not yet immeasurable.… What separates us from the sacrifice is something like vellum.”

Ambivalence may well be the reality of our day. But as Khalid’s characters learn, one must, inevitably, make a choice. If a story is a yarn, let the line be taut, the thread firm, the wheel continuously spinning. But if it is more like vellum — a thin film between our world and the truth — why not pierce the barrier and let the chaotic world break through?