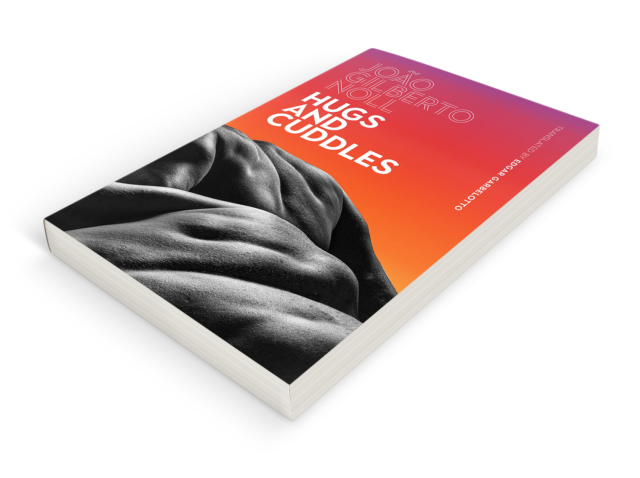

Hugs and Cuddles

João Gilberto Noll

Translated from the Portuguese by Edgar Garbelotto

Two Lines Press, 274 pp.

I always thought Jean-Paul Sartre’s idea that humans are condemned to be free sounded a lot like being adrift after a breakup. Your obligations evaporate. Your ex-lover’s opinions and expectations are replaced by silence. You are suddenly able to do whatever you choose. And the freedom is unbearable.

Like me, Brazilian writer João Gilberto Noll (1946–2017) may very well have conflated radical freedom with a lovelorn existence. In his 2008 novel Hugs and Cuddles, recently translated into English by Edgar Garbelotto, love offers a man the tantalizing illusion of having escaped from freedom, of having surrendered all responsibility to someone better equipped to handle it. At the same time, for Noll, this self-abnegating love is also a catalyst for a new kind of political unity.

Our narrator, João Imaculado, who is of German, Portuguese, and Native Brazilian ancestry, has a wife and son in Porto Alegre, a family farm near Jaguarão, and a penchant for cruising in unlikely places — a World War II submarine, a butcher shop, the jungle. But the main object of his affection, and, in many ways, his chief opponent, is a man known to us simply as “the engineer.” As one comes to expect from a novel by Noll, whose other books include the nihilistic and tender Atlantic Hotel (1989), the anxiety dream that is Lord (2004), and the madcap erotic farce that is Harmada (2013), João Imaculado takes being in love to the extreme. “I was offering everything,” he confesses, “letting myself become enraptured by what was unfolding.”

By offering everything, the narrator unwittingly — though quite willingly — becomes a prisoner of love. One night when he is out by himself, he is badly beaten. He wakes up in the hospital and is told that his face has been damaged beyond recognition. Before he can do anything, he is declared dead and buried alive. The engineer rescues him and brings him to the outskirts of Cuiabá, to a minimally furnished brick house. There, the narrator realizes he can start his life over — “I was Lazarus, but nobody should know that” — and the engineer “would be my man.” The engineer, it would seem, has set up the house for the two of them to cohabit as husband and wife.

“So,” the narrator concludes, “I would take care of the kitchen and prepare good meals” and “clean and do laundry, too.” He decides, “If I organized my days according to this mysterious plan, I’d be rewarded with the engineer’s body every night.” The only catch: he’s not allowed to know what the engineer does for a living.

In a 1945 lecture titled “Existentialism is a Humanism,” Sartre likened the person who denies their freedom to a corpse — a mere thing. Under these strange new circumstances in Cuiabá, João Imaculado begins (joyfully) referring to his body as a corpse and, around this time, starts noticing changes in his corpse’s physiology. The hair on his head suddenly grows a foot in length, his beard falls out, and he welcomes, with wonder and excitement, new breasts and a new clitoris. “I was journeying into womanhood,” he observes. “And for the rest of my days, I would live in the ecstasy of this female abstraction.”

As it turns out, however, João Imaculado’s transition is neither absolute nor linear. Just as the shape of the narrator’s face becomes ambiguous after the attack, his body, too, becomes an immaterial, almost imagined, space for linguistic play. Ultimately, he is whittled down to his essence: a voice. Consider the following passage: “In my pelvic region, the rumble of a certain concavity made itself heard like a nocturnal, subterranean call, though still uncertain — a cauldron boiling the sauce for my new focus of delight.” Deeply in love, the narrator’s body seems to be composed entirely of simile and metaphor. Physicality comes to rely on poetics, and vice versa.

It’s in this poetic narration that Noll starts to redeem João Imaculado, whose self-abnegation has led him to abandon his family and refuse his existing obligations to the world. In some senses, he has never been more free — more fluid — even as he longs to be determined by another. Though he may refer to his body as a corpse, it is evidently an unusually dynamic one. Perhaps allowing ourselves to be corpses for others — to be projected upon, to be relationally defined — is not such a bad thing. Just as we are relational beings, gender and its requisite politics may also be relationally defined, as nuanced as language, and as fluid as emotion.

Totaling nearly three hundred pages, Hugs and Cuddles takes the shape of a single, rambling paragraph, full of recurring phrases and puzzling asides, though individual sentences are surprisingly self-contained, syntactically sound, and even on the short side. (It’s less Molly Bloom’s soliloquy and more Édouard Levé’s Autoportrait.) As in Noll’s previous novels, the narrator can alter reality with his words alone: his body can take any form imaginable, he can claim to possess both “doglike loyalty” and the impulse to deceive and betray, and he can be dead and alive at the same time.

By choosing such a cascading and breathless form, Noll locks the reader into the same terrifying zone of freedom that the narrator occupies. Since Noll provides no text outside of João Imaculado’s monologue, the narrator essentially creates himself from scratch. Afloat on the cadences of his own voice, he flounders in the freedom his soliloquy affords him. The impulse to tell a story lies beneath his verbal gymnastics, but it struggles to surface. For that reason, it is João Imaculado’s distinctive voice and stylistic bravado, not so much the plot, that readers will remember.

Indeed, the language absolutely shimmers in Garbelotto’s artful translation from the Portuguese. Take, for instance, the narrator’s apt characterization of himself as a “dispersed man,” or this nimble sequence of events: “I get dressed to go out. I step carefully; the house is asleep. I close the door, pianissimo. The moon is an invitation.” And, finally, this achingly intimate metaphor for romantic reciprocity: “If I could wear his underwear, and he mine, life would be partially resolved.”

Although the novel’s setting isn’t anchored on a specific historical event, there is reason to believe the book is set during the 1980s, a time when Brazil was targeted by international drug trafficking organizations and cocaine was shipped in large quantities through the country. As the narrator observes with vague amusement, “The situation in Brazil is getting worse,” and the engineer, it turns out, is the “prince of drug trafficking in Southern Brazil,” responsible for distributing “ruthless” amounts of cocaine “for the metaphysical recreation of men and women.”

Enmeshed in this state of national decline, the narrator is periodically approached on the street by strangers asking for donations. At times described as a continental charity brigade, at times a campaign embezzling collective funds, the strangers all seem committed to an unnamed cause. Each time, albeit reluctantly, the narrator surrenders something of value on his person, from a chain around his neck — a gift from his mother — to the wedding ring on his finger. Afterward, he thinks, “I had fulfilled my duty, even though I hadn’t learned the exact cause of the campaign.”

Here, the reader notices a consonance between the narrator’s openness toward unknown erotic encounters and his “goodwill in the face of the unrecognizable solicitation for help.” João Imaculado may not be the ideal family member or the ideal citizen — aloof as he is from the details of his past life and his political reality — but he offers himself to the world, nonetheless. And Noll offers more admirable models of civic duty elsewhere, fleshing out the spectrum of possible modes of being in a community: As João Imaculado recalls, on the road from Cuiabá to La Paz, Bolivia, there is a truck stop where many Brazilian prostitutes work. There, an elderly woman is rumored to walk from truck to truck “distributing pieces of toilet paper to the participants of the nocturnal programs.” Some say she used to be a sex worker; others say she experienced “the pains of Christ in the Calvary” and is now a saint. In any case, she is “content to distribute fragments of genuine compassion” in exchange for a chance to spy on what happens in the trucks.

What might it look like to give yourself to others, beyond what existentialists call a dishonest denial of your undeniable freedom? Could we rebuild a political community based on the values by which João Imaculado lives? These are the questions Hugs and Cuddles asks us to answer with increasing urgency, as its narrator journeys deeper into isolation, codependency and, ultimately, a struggle for survival with and against his lover.

In a 2020 essay for The Guardian, Garth Greenwell described his goal of portraying gay male relationships in his fiction, “whether partnered or promiscuous, durable or transient,” as “models for sociality” beyond prescribed heteronormative structures like the single-generation nuclear family. Likewise, Noll’s novel proposes a new model of sociality, one in which sexual reciprocity is the basis of social exchange. Here, erotic encounters become testing grounds for new political systems and kinship configurations. In this fictional world, where values such as fluidity, collectivity, and jouissance prevail, where bodies are constituted by desire and condemned to be free, self-renunciation may be the key to communion.