In our “Object Permanence” series, we ask authors to write about a physical artifact with an outsize presence in their memory.

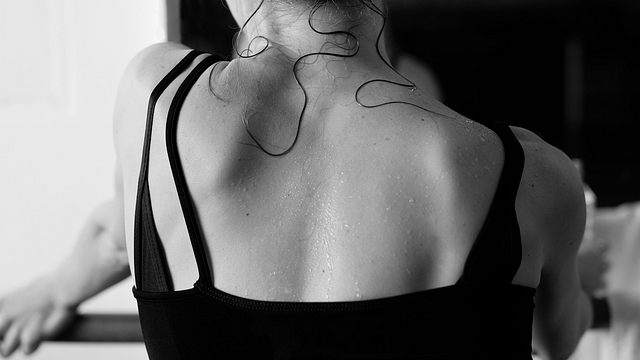

Her leotard was elaborately patterned with sweat. Unlike our standardized sweat distributions — peninsula of saltwater dangling between the breasts, a patchy island on our backs, cotton straps wilting — her sweat mapped out a strange and sublime archipelago. The rivulet running down her thigh like a sheathed sword, the Rorschachian mottling that bridged her hips, the shadows we so badly wanted to span with our hands. Looking at the skinned pelt of her leotard, it was impossible to tell how its creature was designed to move, whether it held itself horizontal or vertical. The asymmetry of her secretions was so sinful in our world of organized limbs and aligned spines that we were all scandalized when, instead of balling up her leotard inside her bag as if it were a shameful rag, she hung it up on the rod in the dressing room, allowing it to sour the air like an open mouth.

When rehearsal was over, she undressed in the plywood-walled dressing room at the back of the studio, while the rest of us faced our cubbies and did not look at each other, having all silently agreed that we were not permitted to shed anything in her presence. When she strode out of the room and down the moss-carpeted stairs, leaving us all behind, I gazed reverently at her leotard — coral-pink to match our role in the sea — trying to decipher its intricacies. The shapes of her stains were as miraculous and incomprehensible as peacock feathers, all spots and streaks and whorls. With my fist in my mouth, I pledged my loyalty to her polyester. She left it there, I decided, to remind us: we were here not to bury our beasts but to buoy them, to hoist them above our heads.

Once a year, we were selected for our roles in the Chinese Opera, and our studio doubled as a rentable recreation room and rehearsal space. When we convened upstairs where the ceiling and walls were padded with insulation foam, we could hear the singers below us, their voices slippery as minnows, brief flickers between our teeth. Nine of us were selected for a fan dance that took place underwater, and our handmade headpieces were designed to impersonate coral, red duct-tape routed into antlers. We were told our orange-pink leotards would appear majestic in the proper lighting, but mostly we felt like raw slabs of salmon.

She was the tallest, and so theoretically should have been relegated to one of the outer edges, where tall girls stood like symmetrical bookends. But on the first day of rehearsal, she was lifted by the thin skin on the back of the neck — yanked around as if by a mother cat — and dragged into the middle of the floor. Her placement made her even more worthy of worship. She had defied her physical destiny, which was all we ever wanted. We were here to disobey the density of our bones, to be made into lace. We loved the delicacies of preparation more than actually rehearsing, which was when we were consistently disappointed by the translations of our exertion, our legs a mangled language. She alone was capable of turning the wall-wide mirror into a fishbowl, spinning and flicking and circling inside its container as if it were an entire world, the only one we would know. She mothered her other species in that mirror, while we remained stubbornly singular. Her feet didn’t have a high arch, but they could bridge time, her heels grinding the future into a powder, her toes providing a perch for the past. Our teachers talked of effortlessness, how to leap without the concept of labor, but she was not relevant to the discussion. She was not effortless, just the sea. Another species. Her leotard, left dangling on the rod, could have been used to tempt whales out of the deep. I imagined dismantling that rod often, dangling it over the water like bait, waiting for some creature to claim its covering and leave her bare.

She spoke to me only once, when I accidentally whacked her on the cheek with my fan. All she did was repeat our teacher, though from her throat it was reborn: Don’t let the wrist be a river. Rein the water. Coral can be hard or soft, and it breathes through its skin, a layer of openings. The whole of it inhales.

During our last week of rehearsals, she was consistently two counts late when opening her fan at the end of our variation. Rather than coral polyps blooming open in one undulating movement like a terrible maw, gum-pink and orange and vacuuming everything, we began to resemble a wooden puppet bouncing across a palm, jaw jerking uncertainly. Some of us theorized that this was a purposeful act of self-sabotage, that she wanted to be relegated to an understudy, but I thought that she was like me: she wanted to delay the actual performance, though we were only a peripheral piece of it and could be removed painlessly.

In rehearsal, we were not presentable. Our ugliness was the prize, our legs shuddering, steam coiling in all our crevices. Our hair was allowed to stray into the territory of rain, strands suspended in the air. Our foreheads were oiled into skillets, every surface of our bodies leaping with heat. At the end of our pain was her leotard raised, lanterning our lives, her sweat obeying a different gravity, surging upward instead of chilling in the spoon-curve of her back. It branched across her torso like a great reef, teaching us how to breathe with our whole skins, without needing to narrow our air through a nostril or a mouth. Her stains surfaced from inside us. Her leotard was worldbuilding.