How to biographize Elias Canetti, one of the world’s great autobiographers? What account would be useful? What usefulness could also be made beautiful? What should be the relationship between his own version of himself — his own multiple versions — and this? On the one hand, it would be wasteful to spend this introduction previewing the very same information that will be encountered again, in better prose, in the pages to come (and in the hundreds and hundreds of Canetti’s pages that I didn’t include, many of which struck me on certain days as just as worthy of inclusion). On the other hand, to be too unfaithful to Canetti’s memoirs would be a betrayal: it would be pointless if not merely uncharitable to make a survey of the author’s omissions, obscurations, mutilations, and straight-up falsifications, because my purpose here is to introduce Canetti the Major Writer You Should Read and not to vouch for the character of Canetti the Friend (not a very good friend), or Canetti the Husband (not a very good husband), or Canetti the Lover or Brother or Father or Son (it’s all pretty messy, to be honest).

I might take counsel from Canetti’s wife Veza, herself a novelist of high accomplishment, who once wrote in a letter to Canetti’s brother Georg: “No document that gives access to Canetti’s inmost being must be allowed to survive.”

Or I might take counsel from Georg, who, when Veza asked him to destroy that letter — to destroy all her letters — did not.

And that, I’m realizing, is the best approach: to address myself to the destructions that did happen, to address myself to the burnings.

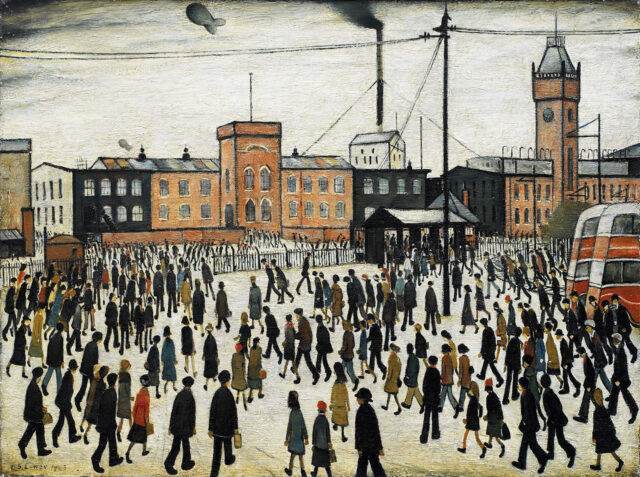

The First Austrian Republic in which Canetti came of age was the fractious remnant of a lost empire, a struggling democracy rived between an entrenched rightist nationalism aligned with industry and the Catholic Church and a diffuse coalition of socialist/communist/generally leftist labor organizations. Each camp maintained its own paramilitaries composed primarily of veterans of the First World War. In the winter of 1927, a rightist paramilitary called the Frontkämpfervereinigung held a rally in Schattendorf, near the Hungarian border, which was considered the territory of a leftist paramilitary called the Schutzbund. The two groups clashed outside the Schattendorf train station and two affiliates of the Schutzbund were shot dead: Matthias Csmarits — a Croatian who’d lost an eye fighting for the dual monarchy — and Josef Grössing, a schoolboy, age eight. Three Frontkämpfer were charged with murder in the Vienna courts, but they pleaded self-defense and in midsummer were acquitted. The day of the verdict was July 15, the day after Bastille Day. The workers of Vienna called for strikes and a street protest turned into a riot. Agitators descended on the Palace of Justice, just off the Ringstraße, shattered its windows, smashed its furnishings, and set its archives on fire. Firefighters arrived, but the rioters cut their hoses. The police responded with bullets, which left nearly ninety people dead and nearly six hundred people wounded.

Among the witnesses to the carnage was Elias Canetti, whose chronicle of the event includes the statement that July 15, 1927, “may have been the most crucial day of my life after my father’s death.”

At the time, Canetti was a 21 year-old student desultorily pursing a medical education at the University of Vienna. He had already lived in five countries (Ottoman Bulgaria, England, Switzerland, Germany, Austria), acquired five languages (Ladino, Bulgarian, English, French, German), and weathered one world war.

What made July 15, 1927, especially “crucial” (only the English has the implication of excruciation and martyrdom) was that it provided Canetti with the scenes and themes — of fires, of crowds — for the two major books of his career. Die Blendung (The Blinding) is Canetti’s only novel, published in 1935. It concerns a reclusive Viennese bibliophile and Sinologist who, at erotic and professional loose ends, or merely channeling the society that surrounds him, ends up torching his own vast library, and in the process immolates himself. Canetti derived the character from an unidentified man in the crowd who, in the throes of the July 15 unrest, was yelling, “The files are burning! All the files!” The question of what would motivate a man to mourn the death of archives amid the deaths of fellow humans was to preoccupy Canetti through the advent of the Nazi book pyres. Die Blendung was translated into English as Auto-da-Fé — the preferred ordeal of the Inquisition, which displaced Canetti’s Sephardic Jewish ancestors from Spain — though Canetti’s original suggestion for the translated title was Holocaust.

Masse und Macht (Crowds and Power) is a nonfiction treatise that Canetti claimed to have begun even before he began the novel, though he published it only in 1960. Its few hundred dense pages of anthropology, sociology, comparative religion, and incomparable metaphysics mine its author’s memories of July 15 to forge a prototype and study of “the crowd,” that amorphous and often arsonous body that Canetti regarded as the ultimate political symbol of his era — a symbol that was also a process, by which individuals become consolidated and absorbed into a mass: “In the crowd the individual feels that he is transcending the limits of his own person.” Note how this transcendence is just a feeling, however, a promise that when unfulfilled causes a reaction of base physicality, of craven violence, which doesn’t always ebb as the crowd disperses: “So long as the fleeing crowd does not disintegrate into individuals worried only about themselves, about their own persons, then the crowd still exists, although fleeing.”

Canetti’s milieu might have been the last in world history to still believe — to accept as a substitute for the belief in God a belief in the attainability of Enlightenment synthesis. Novelists Hermann Broch and Robert Musil were producing books that tried simultaneously to document reality — which was being changed by innovations of mass communication, or media — and to arrange it according to the principles of realism; their writing was founded on this paradox, in which fiction was responsible both for reporting the facts and for making their chaos conform to aesthetic order. Writers of nonfiction, meanwhile, worked toward theories, systems, rationalistic or at least self-rationalizing methodologies of explanation. Think of the Frankfurt School, for example, which erected itself atop the ruins of Freud and Marx. Canetti tried his hand at the epic novel and concluded its pages in flames. He tried his hand at the grand unifying theory of crowds and wound up alone and lonely, claiming he never wanted or needed the followers he never even had. It was only in the memoirs that he achieved the dream of novelistic fluency and programmatic amplitude, though even that series went unfinished. Of the five planned volumes, each to be titled after an organ of sense, only three — The Tongue Set Free, The Torch in My Ear, and The Play of the Eyes — were completed and published. The third volume ends with its hero at his mother’s deathbed in Paris, on June 15, 1937. The author himself went on to London after the Anschluss and never wrote the fourth, a volume dedicated to the olfactory: the smoke of the Blitz might’ve been too acrid. (Party in the Blitz, an abandoned manuscript that never appeared in Canetti’s lifetime, presents the author’s chronicle of the Germanophone émigré scene in wartime Hampstead, and, aside from vibrant sketches of Arthur Waley and Franz Boas, is most notable for its pungent treatment of Iris Murdoch. As for a fifth volume dedicated to touch: the cheek-by-jowl masses of Crowds and Power must suffice.)

The more distance Canetti had from Mitteleuropa, the less interest he evinced in a totalizing prose project, which he came to associate with totalitarianism. It was as if the book that had once aspired to contain the world had now become the book that could only confine it and chain the author to his desk, his chair, his first-person singular pronoun and its convictions. Where once certainty had obtained, mistrust and doubt were setting in, which might explain why, when the Swedes awarded him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1981 “for writings marked by a broad outlook, a wealth of ideas and artistic power,” Canetti accepted mutely: he gave the Stockholm crowd no lecture.

Canetti’s late-life writing, both before and after the Nobel, consists almost exclusively of Aufzeichnungen, a bureaucratic, even clinical word that can be translated as “records,” or “recordings,” or “briefs,” or “notes,” which Canetti applied to a diverse array of texts —traditional aphorisms, feuilletonesque caricatures, mock-Socratic dialogues — that all had their origins in his notebooks. Canetti’s daily dedication to these notebooks turned them into the realest of his memoirs, almost a real-time diary of his thoughts, with hardly any autobiographical content. Faced with the prospect, or with the dread, of publication, Canetti would often merely cull from these notebooks, making various selections: The Human Province, for example, contains Aufzeichnungen from 1942 to 1972, while Notes from Hampstead contains Aufzeichnungen from 1954 to 1971, though the volumes have scant overlapping material. At other times, Canetti would take one or more of his Aufzeichnungen as the basis of a theme, to guide his further writing in the development of standalone volumes, such as Earwitness, a miscellany of character types, and The Voices of Marrakesh, a travelogue. It was in the Aufzeichnungen, and through his reading of classical Chinese philosophy, and of Kafka, that Canetti finally came to terms with the principle of incompletion, and to understand it not as a failure of the artist, but as a triumph of art — specifically, as a triumph of art over death, because the aura cast by incompletion made that art into a mystery for the future. To make something unfinished — to set out to make something unfinished — was to enlist the imagination of the generations to come, should they be up to the task, should they even comprehend the task. Canetti’s final book, the posthumously published The Book Against Death, is the epitome of that challenge.

Almost three decades after Canetti’s passing (Zurich, 1994), here he is again, in America, a country he alternately ignored and derided. I can’t help but wonder which favor America will return on this occasion. I accepted the honor of putting Canetti between fresh covers because I, like pretty much everyone else during the past two years of pandemic-caused lockdown and crowd avoidance, became interested in “freedom” — rather, I became interested in why I’m often ashamed to speak that word, and why I’m often ashamed to admit that I’m ashamed to speak it, and so on. Perhaps my reaction has to do with the clunk of the verbiage itself — I can’t help but regard that “-dom” slapped onto the end as vaguely sadomasochistically sexual — or perhaps it’s the hint of sanctimony or sham piety with which it tends to be employed. In Canetti’s youth, peoples — entire ethnicities, entire races — yearned and fought for collective freedoms and self-determined governance. Consider the innocence of early Zionism, or the patriotic fervor of Ottoman-and Habsburg-era Bulgarians, Romanians, Slovenes, Croats, and Poles. But sometime after the Second World War, in which Germany failed to re-create by force a perverse version of the empires that crumbled in the First, these notions of autonomy suffered a contraction, especially in America: now the entity seeking freedom was doing so not in an imperial but in a national context and was more likely to be the subgroup (female, gay, black), or the individual subsumed into multiple groups at the intersections of depersonalized identity.

It might be that my discomfort with the word “freedom” is only my discomfort with the exclusionary politics of those who abuse it (in much the same way, I’m disturbed by the exemptionary politics of those who abuse “liberty”). But then it might also have to do with the fact that I was born in 1980 and so grew up in an America that was still cheering the collapse of the Soviet Union when it was attacked by religious fundamentalists and reacted by declaring war on the world — an endless technologized jihad of surveillance and control that by now has lasted half my lifetime. Whatever the cause of my word-aversion, the fact remains: as I became an adult, I found it harder and harder to write the word “free” without irony and to read the word “free” without thinking that it referred to something that cost nothing. As a writer — not just as a writer in a free society, but as a writer period — it sometimes feels as if I possess, or would be able to possess, every freedom except one, which is the freedom to be unpolitical, the freedom not to have my every sentence be judged by the terms of my identity, as construed by each of my readers.

Canetti, exile, cosmopole, polyglot, was among the first modern voices who refused this — among the first modern voices who refused identity and politics and their conflation in what’s now called “identity politics,” which his Viennese experience told him was the primary sign, or symptom, of the individual’s absorption by the crowd, or of the crowd’s co-option of selfhood and independent conscience. Canetti’s scorning of this crowd-consumed human was akin to his scorning of Freudian orthodoxy and of the fashionable Marxist, or Marxish, Frankfurt thought of Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse, and Habermas: he abhorred the former’s tendency to relate all behavior and ideation to trauma, just as he abhorred the latter’s tendency to relate all behavior and ideation to capital. “I want to keep smashing myself until I am whole,” this indefinable, unassimilable Spanish-Jewish, Ottoman-Balkan, Viennese, British, Swiss world citizen wrote in one of his Aufzeichnungen from the start of the 1950s, when Europe had been smashed and wholeness was no longer the property of crowds but the ambition of the information-crowded individual.

Canetti’s destructive-creative act takes the violence he witnessed in Vienna and turns it inward: the smashing that he’s advocating is one in which we individually shatter our superficial vocabularies and politicized identities of false belonging and go sifting through the rubble for the common thoughts and emotions that underlie them and connect us with others and enable us to imagine and inhabit other lives. It’s this Ovidian ideal of mutual imagination and inhabitation that inspired “The Profession of the Poet,” an essay-manifesto in which Canetti declares:

A poet should try, no matter the cost, to preserve a gift that once was inherent but now has atrophied, and he should do so in order to keep open the doors between people—himself and others. He must be capable of becoming everyone: the smallest, the most naive, the most powerless. But this desire to experience others from within can never be determined by the goals that compose what we call our normal or official lives. This desire would have to be completely free from any hope of success or achievement; it would have to constitute its own desire: the desire for metamorphosis.

Whether an “inherent” poetic gift granted by the gods, or an “atrophied” speech freedom guaranteed by the state, this metamorphic ability to “becom[e] everyone,” this protean desire “to experience others from within,” remains unrealized for most of us — writers very much included — unwilling as we are to step from the crowd and perform its destruction on ourselves.